Callum Morton, Monument #32: Helter Shelter

Rex Butler

There it sits in Alfred Deakin Place off the main street of Ballarat, just as confronting, divisive and aesthetically repugnant as the original on which it's based. It's Callum Morton's Monument #32: Helter Shelter (2018), a huge papier mâché reproduction of the top half of American President Donald Trump's head. It's all there as we so unwillingly remember: the fake yellow suntan, the thinning white teased pompadour, the narcissistically slitted eyes.

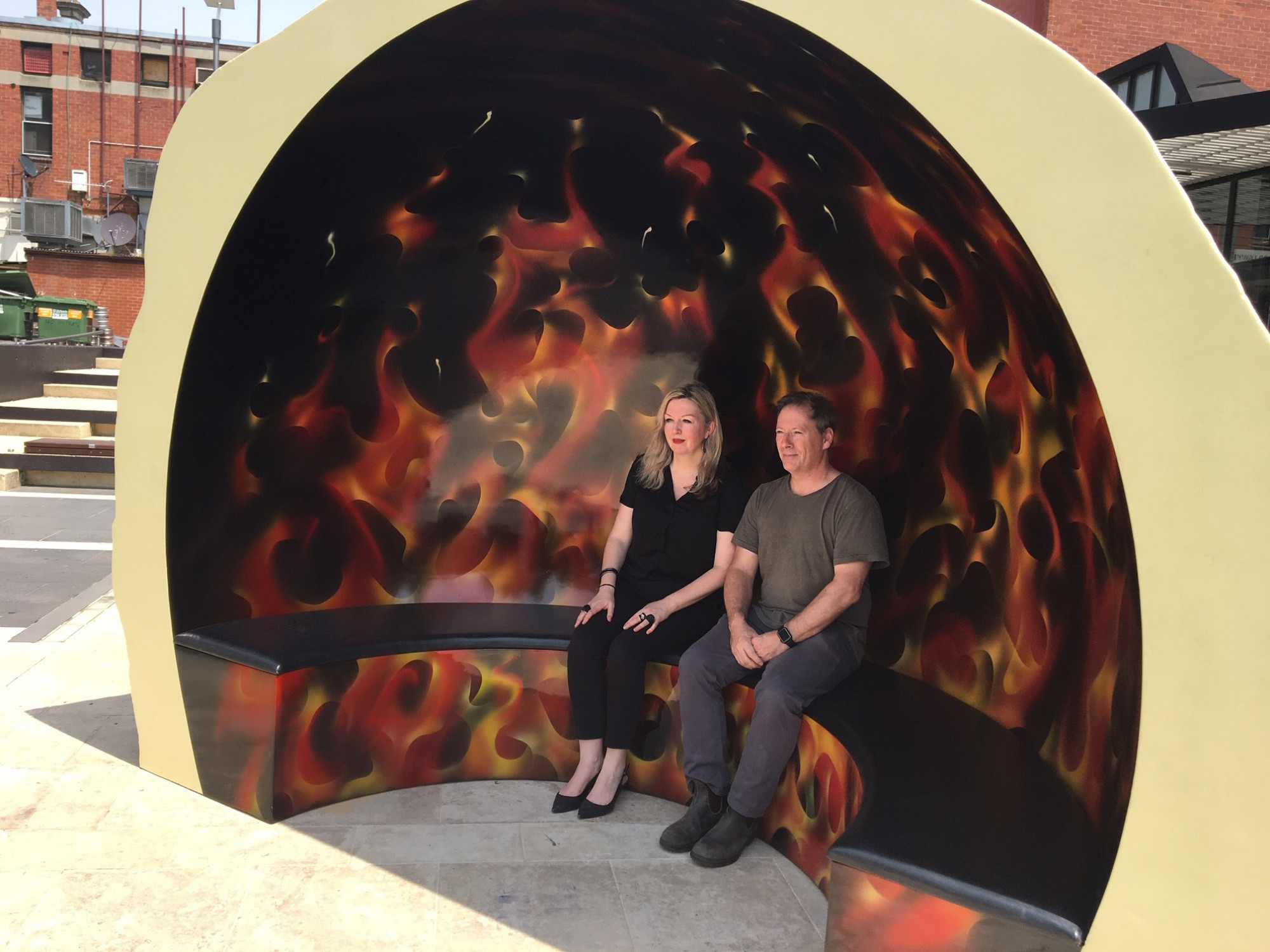

It's enormous, fading in the sun and ramshackle (it's evidently hollow, without you having to rap your knuckles on it to find out). And you're meant to sit in it because behind the facade on the other side is a hidden bench in an alcove with room for several people.

The idea? To put yourself in Trump's head for a while, whatever that would mean. To empathise, to sympathise, to know for a while what it'd be like to be Trump. To listen from the other side to what people say about him—and you only have to stand looking on for a while to hear all kinds of weird and revealing things being uttered in his presence.

Of course, in an obvious sense, it's an astonishingly provocative gesture to stick this sexist, racist, anti-immigrant American triumphalist in a humble country town square. Especially when nobody seemed to ask for it except the local art gallery and the city's “creative team”. The Ballarat Courier ran with such headlines as “Massive Trump Head Coming to Ballarat”, and there were angry letters in the paper complaining that it was totally inappropriate to foist Trump upon people in this way. The same thing happened in Sydney when it was shown as part of the Sydney Contemporary Art Fair. In both cases, security guards ended up being called in to protect the work against enraged onlookers.

The work has brought a lot of attention to Morton the artist too. Why do something so seemingly emptily sensationalist as this? What is Helter Skelter's relationship to Morton's other work (the example the newspapers invariably mention is his Eastlink Hotel (2008), the miniaturised yet still massive tromp l'oeil hotel on the right hand side of the M3 when driving from Melbourne to Frankston).

Its public exhibition puts a lot of pressure on the artist, and maybe even art itself, to justify the piece. Is he in any way sympathetic to Trump? Why does he think art has anything important to say about a phenomenon that is discussed every day at length online, in the newspapers, on television?

In an interview for the left-leaning Guardian newspaper ('This is an Ugly Work': Trump's Giant Empty Head Descends on Ballarat”, 15 January 2020) Morton is very particular to begin by emphasising that he has absolutely no sympathy for Trump. “I am interested—actually I am appalled—by these hard-right, alt-right figures”, he says, before continuing: “People who like Donald Trump are crazy. (Alt-right figures only) draw on imperial nostalgia to reassure people”.

But then—and we have to understand that this is the necessary other half of the same “progressive” attitude, what allows him to speak to the art and not just political constituency of the Guardian—Morton adds: “Ultimately though, I don't dictate how people read the work. Everyone will bring their own thing to it”.

This is the default position of all contemporary art today. When a curator from a hip institutional gallery, understood to be an expert in their field with something to say, gets on radio to spruik their upcoming show, their inevitable line is that it is about something—about painting, about Australian history, about some pressing social issue. They would never dare say what the show was actually saying about these things. The idea is not to answer questions, but to ask them. In today's world, it would seem unacceptably authoritarian to seek to impose one's views on another, to try to tell them what to think. It is rather a dialogue between the work and its audience, in which each respectfully listens to the other without saying anything themselves.

Undoubtedly, the origins of this attitude go back to the Minimal Art of the 1960s, in which, in the words of Donald Judd, “A work needs only to be interesting”, and its real subject is the relationship between it and its spectator. The idea of some intentionality, the sense that the artwork has something to say and we must try to understand it, is over, replaced by a vague and generalised “experience” in front of the work.

And undoubtedly the contemporary equivalent of this, the justification for any number of artist collectives, open-ended academic symposia and jet travel to foreign lands, is relational aesthetics: the idea that the real justification of the work of art is the sociality brought about by it, the getting together of people in a momentary utopian alternative as opposed to our usual commodified existences.

All of this is a form of populism: an art that seems to be of the people and from the people. An anti-elitist art that's not about the forming of any sensibility or the acknowledging of the authority of any particular work of art or anybody who claims to know anything about it.

In other words—although it's a big jump—contemporary art is something like Trump's pitch against Hillary Clinton in the last US election: that she was entitled, that she was too smart, that she was a creature of the “swamp” of Washington. Against this, Trump was one of the “deplorables” himself, an outsider to the system and prepared to let all those without a voice (but only white, working class and mid-Western) speak. It would be a radical new sociality in which everyone was equal and no one could be criticised (his infamous remark after the racist violence in Charlottesville was that there were “good people” on both sides).

All of this is certainly one implication of Morton's work: that Trump is us just as much as a post-Minimalist artwork is its spectator. We are able to get into Trump's head only because he is already us, just as coming across a Minimalist work in a gallery is like encountering another person in a room.

We all know how this turned out. Under the guise of an egalitarian populism, Trump installed a clique of self-enriching kleptomaniacs—far from “draining the swamp”, he put his own children and in-laws into positions of power in a post-truth world, in which his bedroom tweet carries the same weight as the researched commentary of the expert.

And in the realm of art, the notional making accessible of the work to the spectator in the wake of the death of the author led to the rise of a caste of self-elected curatorial officials and a general dumbing-down in which expertise and authority are unable to be questioned. Today, curatorial choices are cryptic, in-house, inaccessible and more conformist than ever precisely because there is no universally acknowledged or even contested standard by which they can be discussed and evaluated.

Morton's Helter Shelter—referencing the innocent moniker of an English fairground attraction with a spiral slide—is the absolute embodiment of this: the imposing of the head of Trump by the gallery and a council-appointed creative class so that people can make up their own minds. Or is it people simply being able to make up their own minds that has led to the imposition of Trump?

The true power of the work—the only power and possibility of art and of any of us in this post-woke, post-authority world—is its self-implication. It allows me to say this about it. Callum Morton is in my head. Or maybe I am in his.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.