Brent Harris: the small sword

Helen Hughes

Hallucinations between figure and ground flicker across the surface of many of Brent Harris’s compositions in his new exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, the small sword. In the studio (2017), for example, the main figure’s cartoonish outline—that most primitive of compositional devices that distinguishes an object from its background—wobbles and warps, as if filtered through the mottled lens of a mirage. The painting lands end #1 (2017) reads like an aerial view of a meandering coastline, with matte black oil blocking out the landmass and a subtle grey-brown gradient indicating the body of water. Harris has painted an eyeball onto the water near its border zone with the land, which allows the viewer to see both ‘grounds’ as ‘figure’ (or, better, ‘face’)—not unlike the optical illusion of the old/young woman. In the oil painting the other side (2015–17), a cluster of bodies morphs into a backdrop mountain range thereby recalling an earlier 2014 painting also titled the other side, where a group of reclining male figures become the silhouetted mountainous backdrop against which another reclining male nude poses in the work’s foreground, suggesting a fractal-like continuity of figure-become-ground. And, in a series of photopolymer gravure/screen prints executed with master printmaker Trent Walter of Negative Press, again titled the other side (2016–17), ghoulish white faces emerge ever so faintly from smudges of black ink, before retreating again into darkness.

This tension that Harris manages to create and sustain as an image-maker—his capacity to hold our attention on a subject at precisely the same moment that it feels to be eluding our perceptual grasp—binds him into a certain modernist and avant-garde pictorial tradition. The tradition is found in both Cubist collage and the interpenetration of back- and foreground that is familiar to the paintings of Italian Futurism and Russian Rayonism. This interplay between foreground and background (what we might call Harris’s manipulation of gestalt principles of perception) is also echoed in his deliberately ambiguous treatment of absence and presence, and likewise his undecided affiliation with abstraction and figuration. Justin Clemens, for instance, once wrote that Harris’s eyes—which appear as a motif everywhere in the artist’s compositions—are not so much eyes in a static sense, but instead cycle through a series of identifications: they are eyes that become targets become voids become orifices … Harris’s compositions captivate and compel us precisely because of this implied instability between figure and ground, form and formlessness, something and nothing.

What is the significance, then, of Harris’s evident skill as an image-maker? Of his special ability to render visible the in-between and the undecided? A clue can be found in the artist’s repeated use of the title ‘the other side’ for his paintings, prints and drawings. Alongside the themes of sex and death, the spiritual realm and the notion of transcendence are key subjects for Harris, who cites New Zealand modernist Colin McCahon and American abstract expressionist Barnett Newman as major influences on his work. Both McCahon and Newman addressed the spiritual, divine or sublime in their respectively figurative and abstract painting practices. Harris has cited these modernists alongside doyens of the Renaissance—Raphael, Pierra della Francesca, Titian—and their treatment of Christian iconography as being formative in several of his artist statements. The repeatedly deployed title ‘the other side’, one presumes, thus addresses the crossing-over from a base or physical realm into an abstract or celestial order. Yet Harris’s treatment of this subject matter sits at an angle to that of other, perhaps more popular contemporary artists. Bill Viola, for instance, produces hyper-stylised, hyper-symbolic video portraits of individuals crossing thresholds representative of the life–death barrier. His thresholds are typically depicted as identifiable, physical and tangible, the crossing of which therefore produces a distinctly linear temporality: a before and an after. (See, for example, the water wall through which Viola’s subjects pass in his Ocean without a shore of 2007.) Harris’s ‘other side’, by contrast, is always captured in a state of oscillation or transition. He has explained that, in his work, he tries to create the ‘sensation of being in a body … The sensation is only ever forming/transforming, never whole.’ As with Newman, who strove for immediacy and totality in his art (what he, echoing Greenberg, described as the visual over the narrative modality), in Harris’s paintings, prints and drawings, ‘the beginning and the end are there at once’.

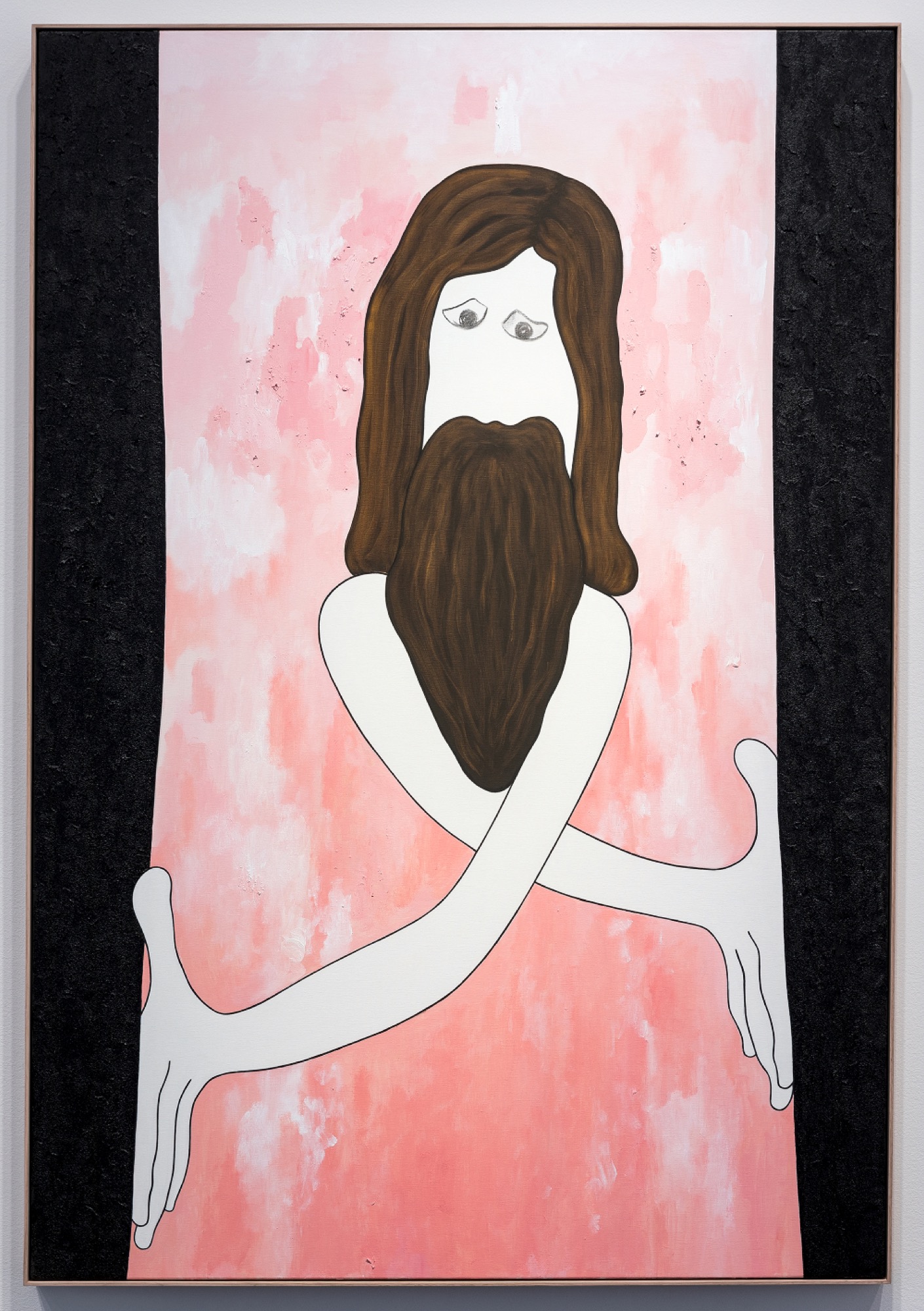

In the Book of Revelation, the beginning and the end—the initials of Alpha and Omega from the Greek alphabet—are used to denote God and Christ. Harris articulates the spiritual through more specifically Christian tropes throughout the exhibition. Both the printed and painted versions of the other side feature cartoon renditions of Adam and Eve who flank the left- and right-hand sides of the composition, turning inwards towards the centre of the work while reeling backwards from their hips away from it, awe-struck. In the early 1950s, Newman famously painted Adam and Eve as vertical ‘zips’ in blood red and crimson hues (Adam, 1951–52; Eve, 1950). They were ‘zips’ because these vertical lines were not intended to separate but rather unify the composition. In one of the most striking and unusual compositions in the small sword, Harris’s portrait-oriented oil painting the visit (2017) mimics Newman’s famous zip compositions in an almost comical fashion. The visit is divided into three vertical strips: two black strips flanking a fleshy pink interior strip. Wedged between the two black strips are the head, shoulders and gangly arms of a bearded Christ figure. Christ’s arms cross in front of his body to push outwards at the left and right edges of the canvas—seemingly in an effort to stave off the encroaching darkness. Instead of the decisive gesture of separation attributed to God in Genesis—of light from darkness, day from night, heaven from earth, dry land from water, and so on—this Christ figure simply maintains a division that could just as soon close up on him again. For all the resoluteness of the canvas’s composition—its thick black cartoon outlines delineating the white skin and the perfectly smooth gradations of the brown hair and beard—at the centre of Christ’s face there is mostly just absence: no nose, no mouth, no cheeks, no eyebrows; just two down-cast, Joy Hester–like eyes, which could also be droopy breasts or cracked eggs, sketched on in greylead pencil. Moreover, these pencil lines appear to have been rubbed out and redrawn a few times. In this way, the sense of becoming—of transcendence as perpetual transition—is not only captured compositionally, but also through Harris’s handling of the medium.

Helen Hughes is research curator at Monash University Museum of Art, and an assistant lecturer in Art History and Curatorial Practice in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Brent Harris, land’s end # 1, 2017. Photography by Andrew Curtis.)