Brave New World: Australia 1930s; Call of the Avant-Garde: Constructivism and Australian Art

Rex Butler

Brave New World: Australia 1930s and Call of the Avant-Garde: Constructivism and Australian Art are both important new museum shows. They involve a serious investment of institutional resources. They demand great curatorial expertise. They make a number of significant art-historical finds and equally propose a number of tough-minded art-historical exclusions. They are, in their various ways, polemical. They change, even if only subtly, our previous understandings of Australian art.

In other words, they're everything we want these large-scale institutions to do and that we often criticise them for not doing. They are not populist blockbusters. They are not imports of shows of world-famous European or American artists from overseas. They are not even the same old rehangs of the already-canonised Australians – Roberts, Nolan, the Heidelberg School – that State and national galleries put on and then attempt to convince us that they are doing their job.

But what accounts for the subtle sense of disappointment – no, that is too strong a word – or rather subtle sense of deflation as one walks around the two shows? It is almost as though – and this goes beyond the undoubted talent and expertise of the curators – one encounters an internal limit to the very kind of exhibition that is being put on there. In fact, what thinking seriously abut Brave New World and Call of the Avant-Garde allows us to do is experience a particular museological problem that bedevils – we are almost tempted to say necessarily accompanies – shows of this kind. The two exhibitions can be seen to raise each in their own way the fundamental irreconcilability between the experience of the work of art and the experience of the museum. And they might allow us to reflect upon – again – what would be required for art to be put properly into a museum context, how the exhibition of a work of art in a big museum like the NGV or Heide might add to the experience of the work of art rather than detract from it.

Brave New World, curated by Elena Taylor and Isobel Crombie, is installed to resemble something like a social history of 1930s Australia. The paintings, sculptures, clothes, posters and photographs are divided up into a series of discrete categories, one each to either a long wall or dividing partition, devoted to such topics as the Utopian City, Body Culture, the Modern Woman, Indigenous Art and Culture, European immigration and the Dystopian City.

Taylor, in particular, is a curator attuned to the new non-national histories of Australian art – her Australian Impressionists in France at the NGV in 2013 is probably the most important exhibition of Australian art in the last decade – and the classic “Australian” art that fits these categories is leavened throughout by an emphasis upon, or at least an awareness of, all those artists usually excluded from the national narrative. Thus we have under the head of the Modern Woman Lina Bryans' oil The Babe is Wise (1940), under the head of Art and Design Sam Atyeo's furniture of the 1930s and under the head of the Dystopian City Ola Cohn's plaster sculpture Sundowner (1932), of an unemployed homeless man made during the Depression.

The show must in many ways be understood as a riposte to the Art Gallery of New South Wales' 2013 Sydney Moderns: Art for a New World, which sought to trace the arrival of modernism in Sydney between the two wars, and featured such much-loved figures as Max Dupain, Harold Cazneaux, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith. Brave New World seeks to contest that version of the story, first by setting the introduction of modernism back a decade to the 1930s – a period that is commonly understood to mark the highpoint of Australia's nationalism and isolationism – and second by widening the story beyond Sydney to the rest of Australia (although, for all of the conscious inclusion of Perth's Harald Vike and Brisbane's Vida Lahey, it still remains a little Sydney-Melbourne-centric).

There are some serious new discoveries and some surprising old encounters along the walls: under the heading of Body Culture, the curators have included the little-known sculptor Jean Broome-Norton, who has only recently emerged after more than a half-century of art-historical neglect; in a chilling hang on the wall devoted to Pastoral Landscapes, we are looked down upon by the beautifully blonde governess of the children of the painter Hilda Rix Nicholas, who has recently been outed as a virulent anti-Semite; looking again at Bernard Smith's colourful Lot and His Brethren (1940), it is evident that Lot, leading his people out of Sodom and towards the Promised Land, is in fact played by none other than Karl Marx, with the same signature beard and furrowed eyebrows.

But, of course, the great drawback of this kind of show is that, for all of the evident art-historical intelligence of the curators, the works of art in them tend to become nothing more than documents of social history. Whatever their own formal principles, difficulties and even obscurities, they become representational, illustrative of the various categories they are classified under.

That is, for all of the emphasis on artistic modernism in the exhibition, its desire to show Australia's connection with international art movements in more detail than ever before, the works ultimately become the emblems of a social modernity. Do the categories they are grouped under actually allow us to see anything new and different in the works themselves? And is this anything inherent to art itself or merely art as an image of the world? Is the ultimate destiny of art to end up in a show like this, telling us a story about the particular time and place in which it was made?

I felt a strong contrast as I walked around the show with the experience of Taylor's Jan Senbergs' retrospective, held on the opposite side of the same level of the NGV last year. There what was literally eye-opening for a once-major artist whose reputation was in decline was how you were forced to look at the hand that made the work, how what moved you about the work and convinced you of its merits was its materiality. You had to see it in the flesh. It was an aesthetic experience. Could the same honestly be said here?

And perhaps the same question might be asked in a more “contemporary” register of the Call of the Avant-Garde show. In many ways, the exhibition, curated by the Heide curatorial team of Sue Cramer and Leslie Harding, had a very similar premise to Brave New World: to trace the introduction of modernism (or modernity) into Australia, this time from towards the beginning of the last century.

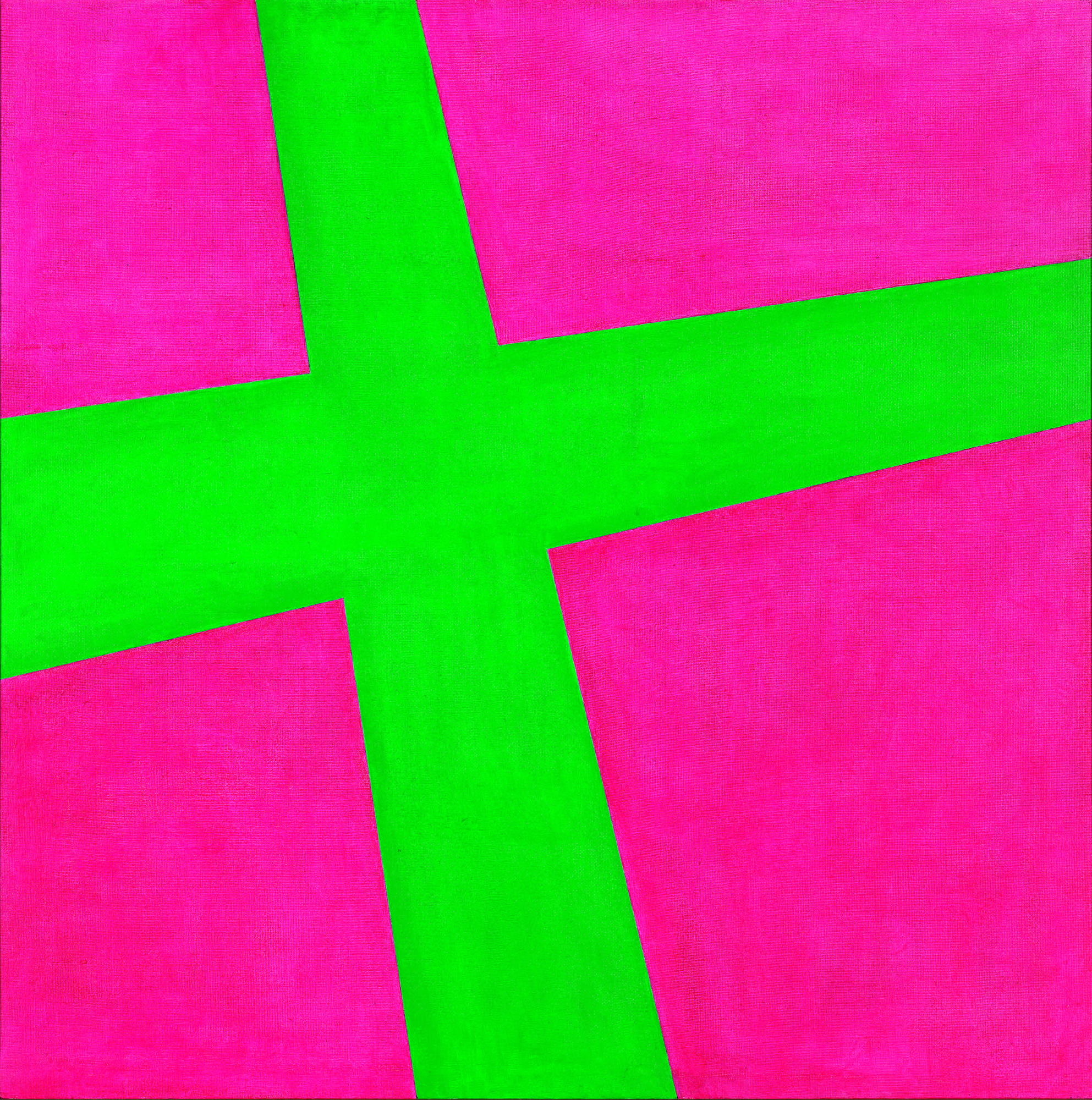

More particularly, taking the centenary year of 1917 as its justification, the show sought to trace both the presence of Constructivism in Australia and how artists here have responded to it since its invention in Russia in the teens of the twentieth century. Thus, for example – and we suspect Heide didn't get all the loans it would have wanted because the NGA, which has a very good collection of Malevich, Tatlin and Rodchenko, is putting on its own exhibition later in the year to mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution (oh, the irony of staging that in Canberra!) – we had an untitled pencil on paper by Malevich of 1915, a lithograph of 1923 by El Lissitsky and an oil on wooden panel by Rodchencko of 1918. And then, after that, there was a long, not-quite chronological hang of Australian “responses” to Constructivism, all the way from Cecil Bostock and Grace Crowley in the 1930s and '40s through Dick Watkins and Margo Lewers in the '60s and '70s and on to Sarah crowEST and the Mangano twins in the present.

In fact, Call of the Avant-Garde is the third in a sequence of retrospectives Cramer and Harding have put on, taking as their subject the story of the arrival of various modernist movements in Australia. In 2009 they curated the perhaps obvious Cubism and Australian Art, which looked at the long reception of Cubism in Australia, and in 2012 they staged the decidedly less obvious Less is More: Minimal and Post-Minimal Art in Australia, which looked at the much briefer reception of Minimalism in this country.

Of course, the first question raised with all of these exhibitions is how do they avoid the default model of Australian provincialism, that is, the idea of Australian artists simply imitating art movements coming from overseas after their original, productive moment is over? And then, equally, how do they avoid the post-colonial variation on this, which is to suggest that Australian artists produce some particular hybrid of the international and the local, in effect adopting selected aspects of what comes from overseas and adapting them to their specific conditions.

To their immense credit, Cramer and Harding have never proposed either of those models: for them, Australian art has always been contemporary and Australian artists have always made work in the same time and space as their international colleagues. (Indeed, Call of the Avant-Garde makes this point by including the work of a range of British, European and South American artists who also worked off the example of Russian Constructivism that has found itself in Australian collections: Barbara Hepworth's Orpheus of 1959, László Moholy-Nagy's Pipe and Glass of 1926 and Julio Le Parc's Continual Mobile of 1966.)

But there is nevertheless a question that runs through this current show that has perhaps been growing in significance since the original Cubism and Australian Art, and that is perhaps not so far from the one encountered in Brave New World.

It is this. Is “avant-garde” really the word we want to describe this “'contemporary” situation? Doesn't the notion of avant-gardism with its inseparable association of artistic modernism impose certain standards, force particular ways of looking at and judging art that many of the works in the show cannot attain? And especially is “avant-garde” really what is at stake in those works made since the late 1960s when modernism as an artistic force and ideology came to an end?

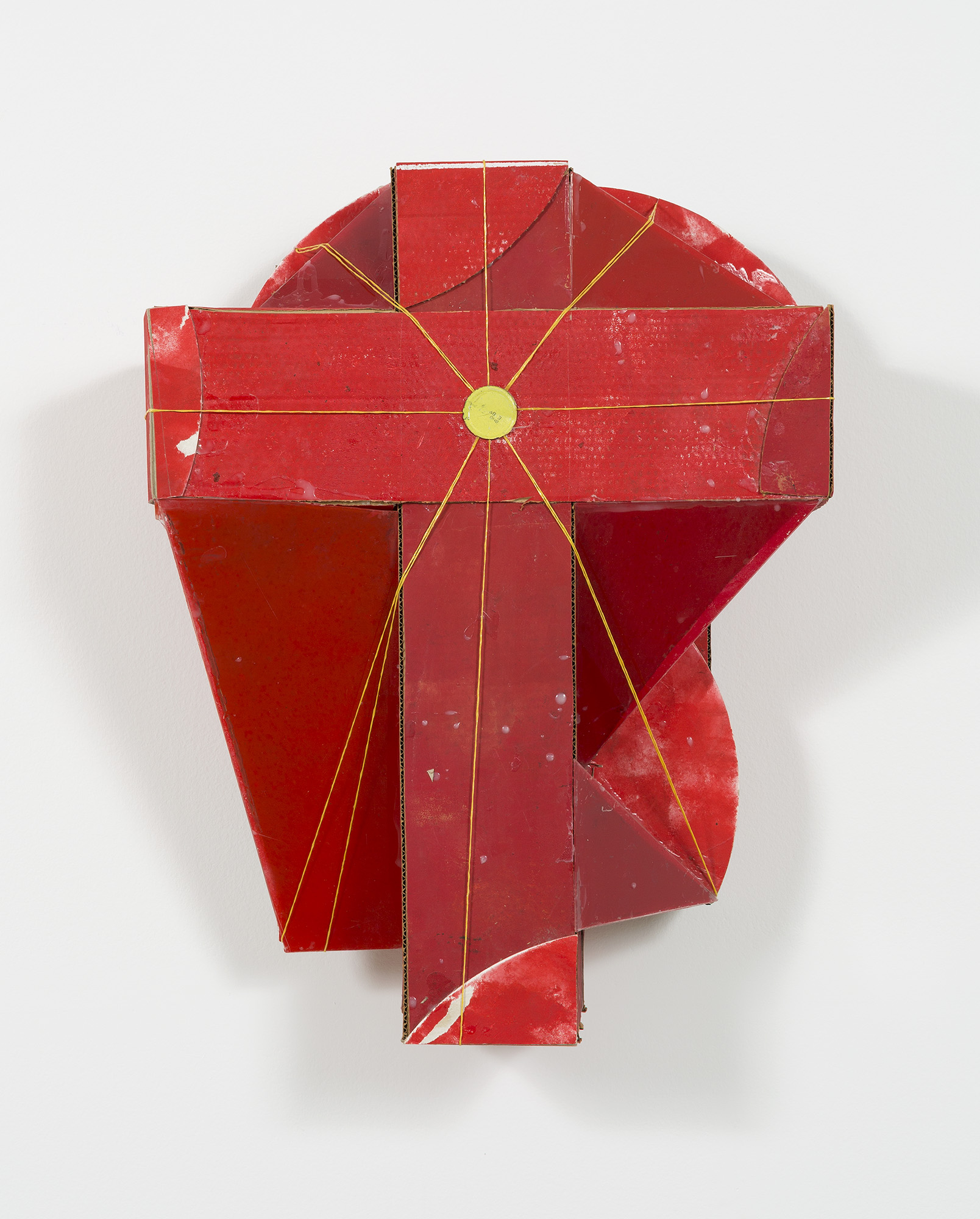

Looking at the work of John Nixon, whose practice and example dominate the second half of the show and in many ways provides it with its retrospective justification, can we say in whatever sense that it is truly avant-garde? On the contrary – and this is the uncanny fact that increasingly becomes evident as one spends time walking through it – the true destiny of his work appears precisely to end up in an exhibition like this one.

It is not that it is art-historically calculating in any sense, or even somehow self-prophesying, but rather that the real interest it possesses is to serve as evidence of a particular time and place. It serves as the marker of a “scene” – Brisbane in the early 1980s, Melbourne throughout the rest of that decade and into the '90s – and the same could be said of the artists who followed him also in the show: Stephen Bram, Bronwyn Clark-Coolee, Melinda Harper, Kerrie Poliness and Gary Wilson. There's virtually nothing to look at in their work, almost nothing of visual interest, except for the fact that it points to a certain kind of artistic activity.

In other words, the principal – if not only – significance of the work is socio-historical, or in more up to date language relational. The work – unlike the original Russian Constructivism – does not point somewhere else but only tautologically to itself and its own existence.

So that in many ways the show is not any kind of exploration of what happened to Constructivism when it arrived in Australia, but merely demonstrates the fact that there were artists here who made work in its name. The result is not any kind of art history but more a social history. Or that, at least, is how it appears once the 1970s begins.

It is a problem that should have been the subject of the show, or perhaps might be of the next instalment in the series. A topic like Australian Art and the Museum would at least be a way of introducing a kind of self-reflexivity into the work exhibited, of thinking how it might relate to its final resting place at Heide, as if not a formal at least a strategical problem and not the incontestable piece of self-evidence it appears here.

Currently on in Melbourne are two shows that raise profound questions not so much about the art they exhibit as about the relationship between the museum and art and art and its history. And the limitations we find in the treatments of even these superbly credentialled curators indicates that something has changed in the notion of the art-history exhibition. If it is not simply to be a spectacle or an audience-driven blockbuster, a lot of serious thinking has to go into what the art exhibition is for in an age of total accessibility. Is the art exhibition merely to make the work of art illustrative, even if only of its own existence?

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Brave New World: Australia 1930s, installation view, NGV Australia, courtesy NGV.)