Julie Fragar, Biograph

Wes Hill

“Are you seeing my conviction?” “Is my candour comprehensible?” These are the types of questions—about devotions, doubts and their semiotic losses and gains—that are repeatedly posed in the work of Gosford-born, Brisbane-based painter Julie Fragar.

Biograph is Fragar’s first institutional survey, currently on show at Murwillumbah’s Tweed Regional Gallery, in the rolling, cattle-dotted hills of Northern New South Wales. Curated by Jonathan McBurnie, the exhibition, which spans more than two decades, first opened at Townsville’s Perc Tucker Regional Gallery at the end of 2022, before travelling to the University of the Sunshine Coast Art Gallery earlier this year (its next stop is the Rockhampton Museum of Art, running into 2024).

Growing up in the tiny New South Wales town of Wee Waa, Fragar has lived in Brisbane since the early 2000s, relocating from Sydney (after studying at the Sydney College of the Arts) to begin her PhD in 2006 at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, where she currently works as a senior lecturer. But as this excellent, unflinching exhibition attests, place and locality largely take a back seat to people in Fragar’s practice, with McBurnie foregrounding how she “approaches her subject matter, including the subject-matter of her own life, as a biographer, taking a comparatively arm’s length approach to firsthand experience.” Hung out of chronological order and without an overarching thematic emphasis, a survey is nonetheless the perfect format to engage with these works, enabling us to get a sense of how they are imbricated with the events and characters of her ever-developing life.

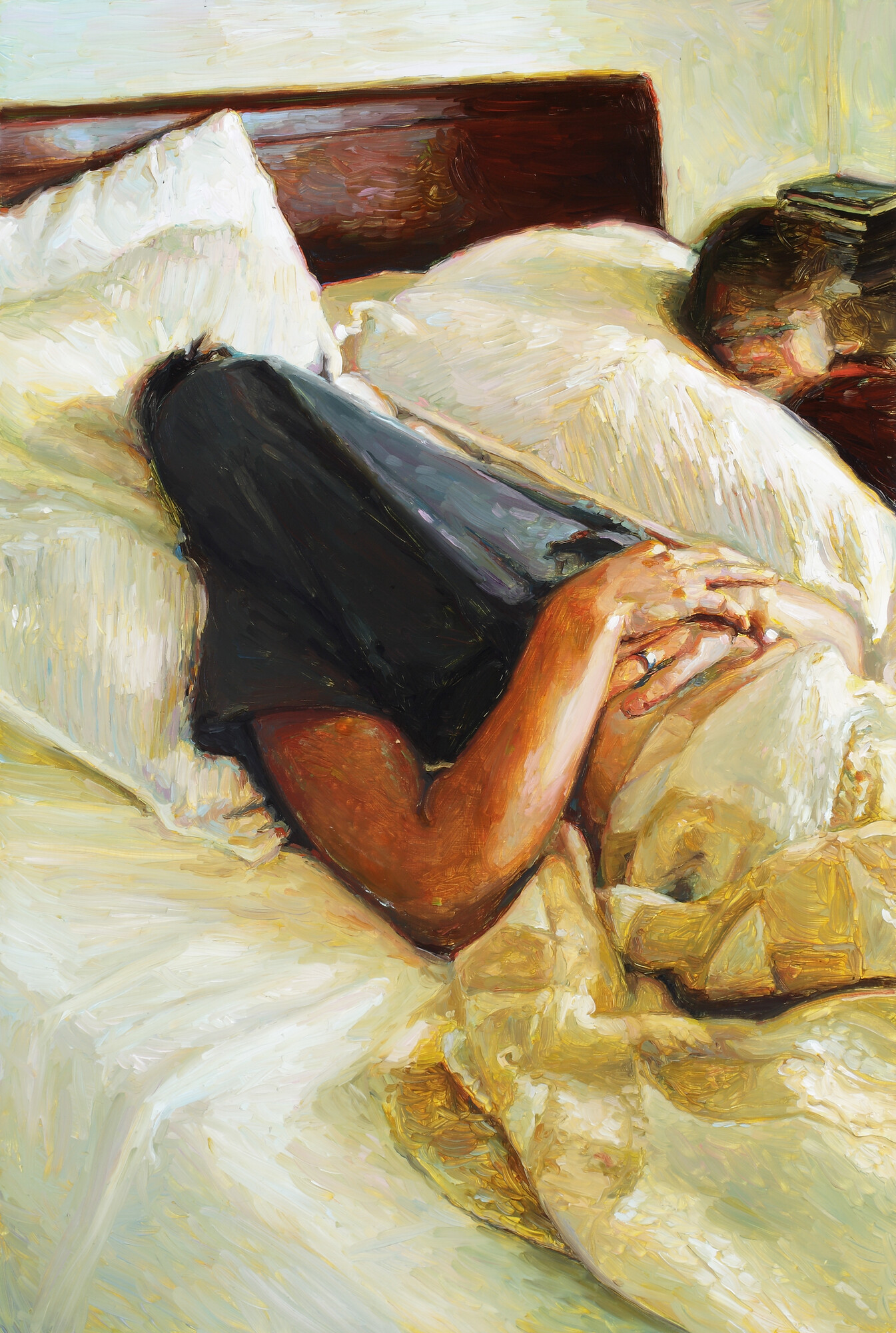

Known for using photographic images—sometimes original, sometimes appropriated—to paint portraits of herself as well as her family and friends, Fragar is an artist consumed by subjectivity writ large. Unlike, say, Michael Zavros (similarly Queensland-based, iconographically minded and only three years older), Fragar zooms in on affections, insecurities, and uncertainties—her textured renderings of photography attempting to communicate something of the struggling human qualities beneath the surface of an image, baring flaws rather than brags. As with the work of late American painter Noah Davis (known for depicting home and family life using a lexicon of images), Fragar’s paintings are both strangely intimate and detached, as much a re-imagining of an inert photographic document as a heartfelt portrayal of a world that really exists.

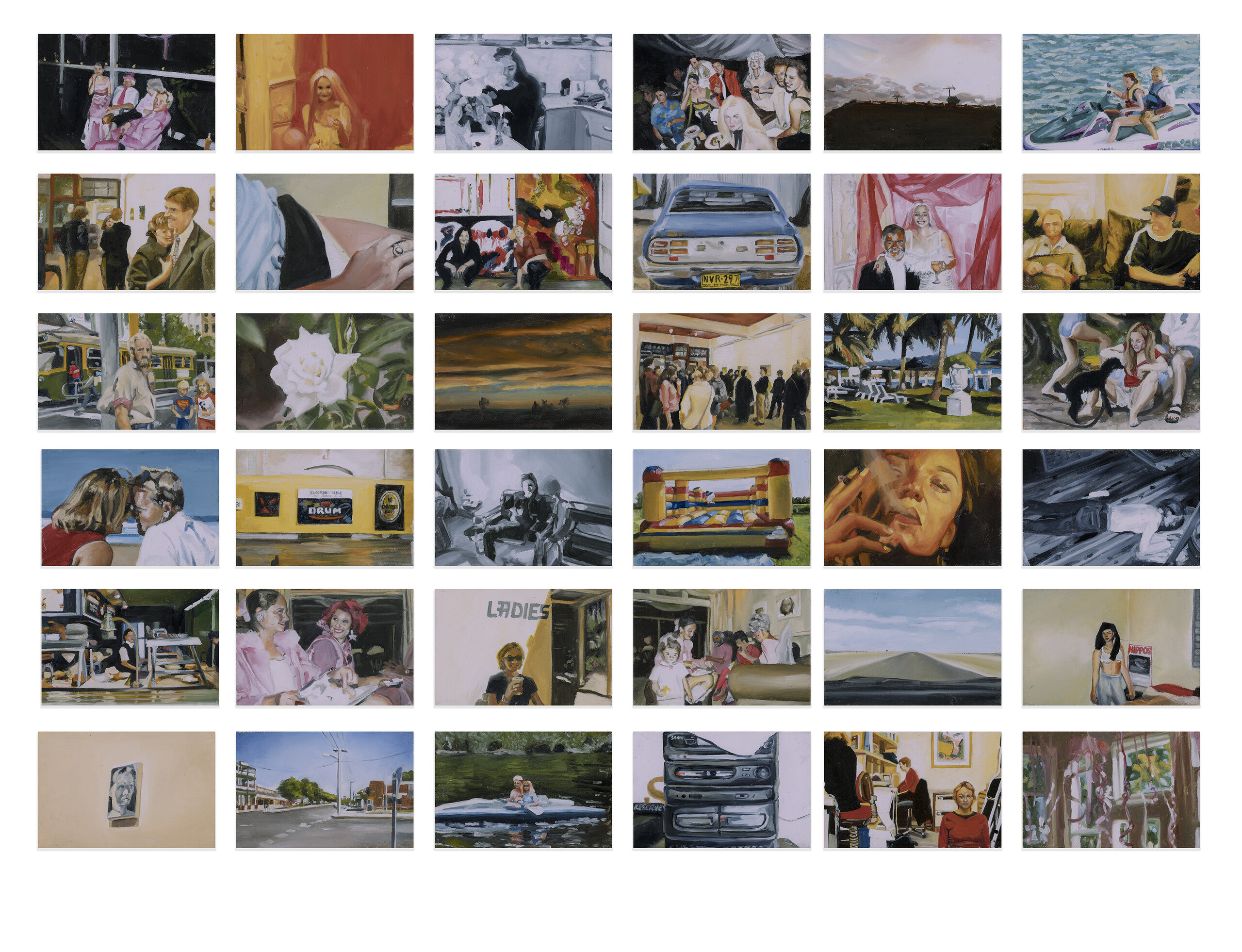

The earliest work here, Apex Jumping Castle, dates from 1998. It consists of thirty-six small ten by fifteen centimetre oil paintings modelled on photographs; they picture, like the title says, a jumping castle, but also a sunset, two people on a jet ski and other seemingly unrelated scenes. These don’t capture private moments so much as indiscriminate shared instances. There is a through-line from this very early work to later works such as Fidel’s #2 (2005)—a black and white painting based on an impromptu photograph of the artist with her young son—and Jump Ship Jump (2009)—a painting based on a photograph showing an Ancient Greek-looking sculpture of a bearded man reclining next to cherub-like babies. From the beginning we can see that Fragar was fixing her eye on the seemingly innocuous moments captured on camera, rendering them in paint as a way of probing any secret singular psychological complexity.

Although Fragar was initially interested in adapting the photorealist work of US artists Richard Estes and Robert Bechtle to her own Sydney-based context, the first decade or so of her career is redolent of what Jordan Kantor described in 2004 as “the Tuymans effect.” Kantor is referring to the effect the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans had on the likes of Wilhelm Sasnal, Eberhard Havekost and others, who, in the early 2000s, were seen as forging “yet another new path for painting through photography … with a unique admixture of scepticism and faith.”

Like Sasnal and Havekost, who share a similar, Hopperesque propensity towards eerie scenes of stillness, Fragar—who actually took more inspiration from Marlene Dumas (another “second-degree” figurative painter) than Tuymans—emerged in a period when painters started to seriously engage with a world taken over by the new tonalities and modalities of digitisation. While an artist such as Gerhard Richter had, since the 1960s, already been attempting to paint photography’s material unreality—as a medium he regarded as “almost one hundred percent picture”—younger artists from the late 1990s on began treating the digital image as though it were an ancillary of screen-based technologies.

The ease of digital photography makes it as much a performance as a material, connecting it to the photographer’s psychology and circumstance, and resulting in more accumulative pursuits. For Fragar, to paint a digital image is to actively reinvent that source material, kicking off her career at a time when there was newfound freedom from the “ideologically laden ideas of craft and skill” that had once been integral to image-sourced painting. Here, in the so-called “atemporal present” of early twenty-first century art, any distance between reality and representation tends to be directed inwards, towards personal imbrications, affirming the lowered stakes of medium delineation as well as chronological classification.

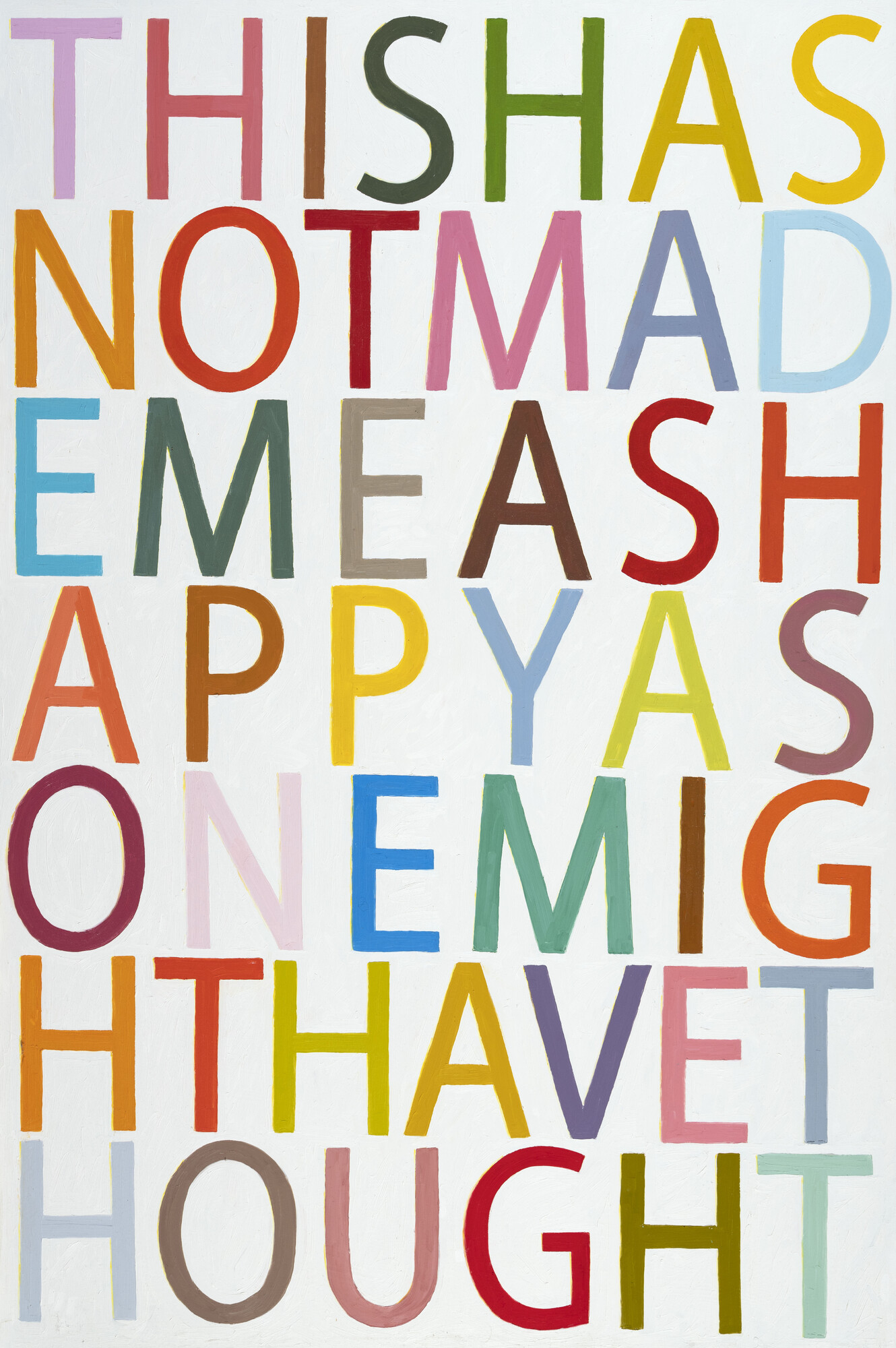

Wandering around the seventy-seven works on display, a definite sense of glum pervades. An artist after my own heart, the works collectively suggest that life ain’t no dress rehearsal. Pensive self-portraits—Stroke (2013) and There Goes the Floor: Self-Portrait (2020)—are shown in view of depictions of dog fights (Marathon Boxing and Dog Fights and Not Your Fault, both 2013), a portrait of a hunter with his catch (Pointing Like an Arrow to the Main Game, 2010), paintings inspired by her attendance of murder trials at the Supreme Court of Queensland (Man Tortures Woman in a Cheap Motel, 2017), and numerous melancholic text-based works, one of which (eponymously titled) reads “this has not made me as happy as one might have thought” (2013), that we see immediately upon entry to the show.

While glum, the works also convey a no bullshit sensibility, therefore situating themselves between two poles, as neither too sentimental nor too detached. Fragar’s “portraits”—which, as alluded to in the catalogue, is a term too limiting for works that have more to do with the artist’s effort to represent empathy for another person than with actually eliciting it—project improbable conflations of vulnerability and subterfuge. The most enigmatic paintings in the show are those that seem resigned to being unable to escape the artist’s own head. Grandma (Alzheimers) (2008), is a 135 by 90 centimetre portrait of the artist’s grandma suffering from the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, staring blankly into space, unblinkingly painted in dark browns and greys.

Fragar has long declared Gustave Courbet as her nineteenth-century exemplar (an appropriated self-portrait by Courbet, Master and Dog in Heavy Black Coats (get up), 2008, is included in the show), but Grandma and other works in the exhibition possibly have more in common with the brooding Romantic artist Théodore Géricault. Fragar may be, like Courbet, a habitual auto-chronicler—which is, according to Michael Fried, “an intense if less than fully conscious absorption” in one’s own bodily being—but she would never be defensive or narcissistic enough to paint anything like Courbet’s 1855 allegory The Painter’s Studio. Summoning Géricault’s 1822 physiognomic portraits of asylum subjects, Grandma chimes with a 2010 statement from Fragar whereby she compared painting photographs to painting dead things—as the paradoxical task of bringing to life how “there is nothing behind the eyes.”

Fragar’s persistent questioning about the control she has over what her work ultimately communicates is (not surprisingly, given our exposure to insipid online platitudes) refreshing. The pronounced vibe of self-doubt has the effect of transforming the dispersed text paintings (a practice she has been pursuing since 2008) into koan-like internal monologues. Often rendered with no spacing or punctuation, phrases such as “your rules are not for me” and “I don’t want to do this anymore” read as yet more creative wrestling with insecurity, expressed in the form of melancholic dictum puzzles.

In a series of works based on accounts of her own ancestry, Fragar’s technique shifts to more layered and surrealistic imagery, utilising a smoother and thinner application of paint, as well as jarring juxtapositions of near and far subject matter. The Antonio series performs the most dramatic shift in technique in the exhibition, which is otherwise fairly consistent considering the time span that it covers. The series explores the mythical family history of Antonio de Fraga—Fragar’s first ancestor to arrive in this country—whose journey on a whaling ship in 1850, aged twelve, took him from the Azores archipelago, Portugal, to far-off places such as Africa, Malaysia, Fiji and, eventually, Australia, over the course of several years (via the occasional shipwreck and encounter with cannibals). Works such as Second Consideration After the Fact (2014) and Off Sure Feet (2014) are as bizarre as any work of German Magic Realism, illustrating the ancestral narrative through uncanny surfaces teeming with birds, conveying all the disjointed chaos that can come with unravelling one’s tenuous genealogical subplots.

Courbet didn’t strive for realism so much as politicise it. Fragar, on the other hand, seems to yearn for veracity even amidst her doubts about whether what she is doing ever achieves it. The exhibition, which I would also love to see hung in chronological order (further situating her career-long process of inquiry over any particular subject matter), underscores Fragar’s relentless attempts to say something earnest about the particularities of her life whilst dealing with its abstracted and potentially apathetic reception in the minds of her viewers

Wes Hill is a Senior Lecturer in Art History and Visual Culture at Southern Cross University, Northern New South Wales.