Installation view, ‘Ten thousand suns’ 24th Biennale of Sydney 2024, Art Gallery of New South Wales, featuring art by Pacific Sisters (foreground) and Robert Gabris (wall) photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Christopher Snee.

The 24th Biennale of Sydney: Ten Thousand Suns

Hilary Thurlow

Although this year’s Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, promised an antidote to all the world’s cataclysms through joy, celebration, and queer coming-together, they were thrown in our faces instead. The perils of war (UNSW Galleries), time-warped apocalyptic premonitions (MCA), unhealing wounds of colonial power, and forced migration (CCWM), and again colonial oppression (Artspace) go on and on. The promises of lively Carnivale were held static in time, unmoving and fixed to mannequins in AGNSW. Is it regalia rallying against all evils, or is it necessary to camouflage to hide from all evils? The new locale, White Bay Power Station, was marginally more optimistic but still steeped in melancholy.

Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, UNSW Galleries, featuring DIGGERMODE (2022) by Joel Sherwood Spring, photo by Jacquie Manning.

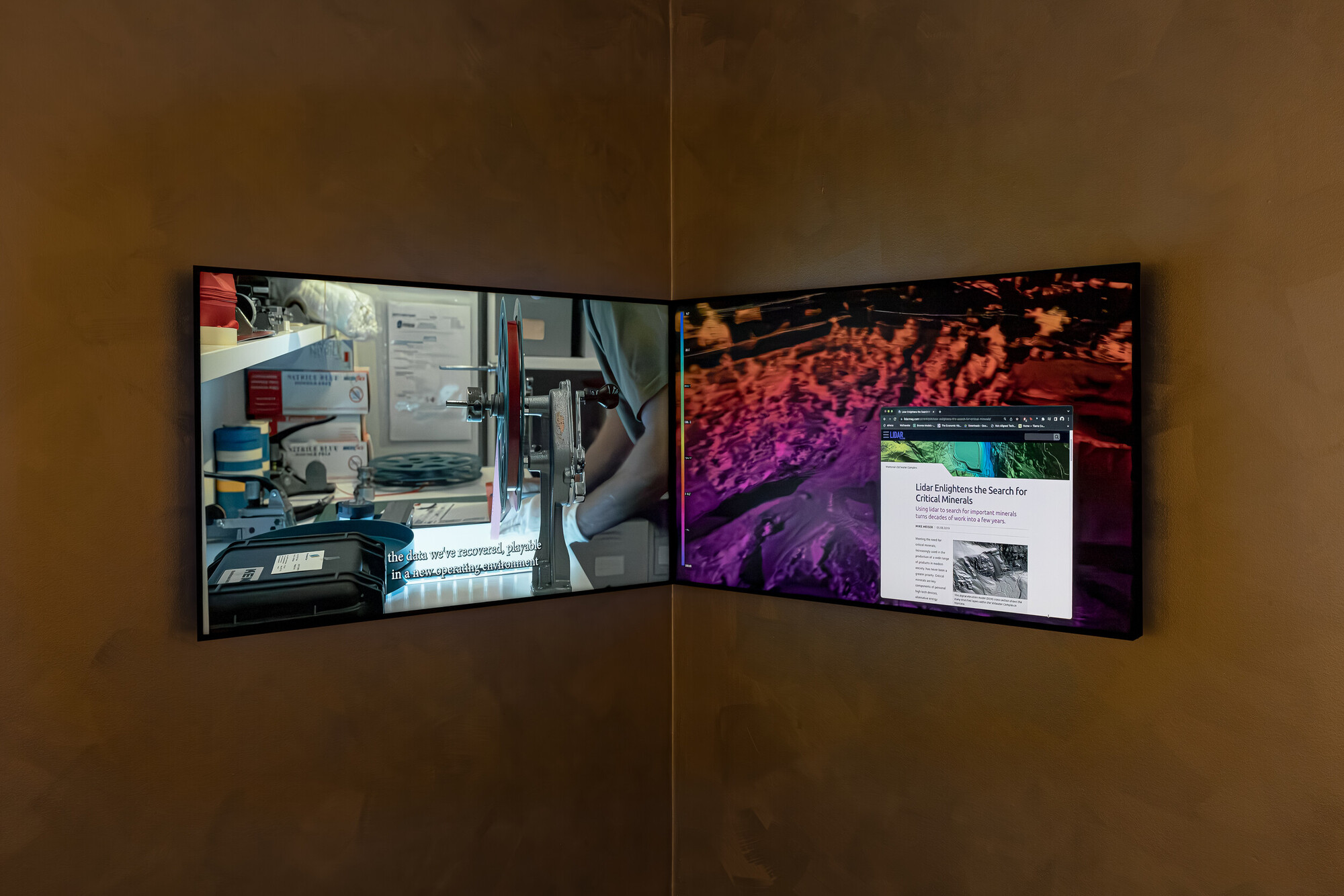

The Biennale of Sydney’s past few iterations have been a fertile breeding ground for young generations of artists (think Aziz Hazara in NIRIN, 2020). But I can’t tell you who such artists may be in this iteration. I guess there was Wiradjuri artist Joel Sherwood-Spring at UNSW Galleries, whose ACMI commission Diggermode (2023) was minimised from an epic two-channel installation—which I’m sure Okwui Enwezor would have labelled as “biennale scale”—onto tiny screens. Think corner of a collection hang tiny. Or Tiwi Island collective Yangamini’s large presentation (also at UNSW) felt squished and minimised compared to the space given to artists at White Bay. Perhaps this biennale was the reprieve from the spectacle we’ve come to expect.

Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, UNSW Galleries, featuring art by Yangamini, photo by Jacquie Manning.

Alas, there was still spectacle, but it was just not for the artists. Coloured walls demarcated galleries in each institutional space. From memory, only Bonita Ely’s Interior Decoration (2013) at UNSW Galleries was left unscathed, housed in its own white cube. I don’t want to dismiss Brian O’Doherty’s qualms or indulge the white-walled vision born out of modernity, but these weren’t just any coloured walls. They were the coloured walls housed in the pages of Better Homes and Gardens magazines from the mid-2000s: mustards, deep reds, teals, royal purples. Not only were these coloured walls migraine-inducing but they also diminished otherwise strong works. For example, Simon Soon’s intricate wooden carvings looked more like home décor hung against a gold feature wall than weighty practice.

Andrew Thomas Huang, The Beast of Jade Mountain:Queen Mother of the West (西王母), 2023–2024. polymer, steel, automotive paint. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from Terra Foundation for American Art. Courtesy the artist2. 4th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, White Bay Power Station. Photo by Daniel Boud.

What about White Bay, I hear you say, where certain artworks were so big they erred on genetically modified, their scale necessary to fill the former Power Station’s void. While the venue was itself an architectural spectacle, within it the artworks were poorly paced. This ultimately denied those small moments of discovery we’ve come to expect from mega exhibitions. Think of those artists whose work you first spied in a biennale—unfamiliar upon first glance—but the practice stays with you long after the show ends. The curatorial choice to present a handful of artists’ work at multiple venues abetted this, too, often curtailing artists’ presentations’ political potency and rigour (Doreen Chapman, William Yang et al.).

It would be remiss of me not to note that this Biennale of Sydney was initially touted as the “gay” biennale—a space where shared celebration interlaced with community was supposed to remedy “it all.” With the likes of well-established collectives Dumb Type and VNS Matrix and elders such as William Yang and Juan Dávila, there was a definite queer bent, albeit no celebration or joy. Take Dumb Type’s video S/N (1994), which centred on the lack of media attention in the early decades of HIV/AIDS, for example. Then there is VNS Matrix’s 1990s unkept promise for a cyber-feminist future.

If this Biennale of Sydney is inflected with a queer method of exhibition-making, I fear it has inadvertently fallen into a Lee-Edelman-death-drive-induced polemic. We’re shown that there is no future here. The ten thousand suns have fizzled, and there is no antidote. Instead, we’re filled with a perpetual cruel optimism.

Hilary Thurlow is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.