Bessie Davidson & Sally Smart – Two artists and the Parisian avant-garde

Jane Eckett

In the suspended time of 2020, it seems permissible to review an exhibition that opened six months previously, closed nearly two months ago and which I never managed to view in person. While these may be less than ideal conditions, they have allowed multiple repeat visits over time via the Bendigo Art Gallery’s online “walk through” video and interactive panoramas of the exhibition installation as well as a more leisured reading of Tansy Curtain and Catherine Speck’s well researched and reassuringly tangible printed catalogue. And this in turn has afforded greater time for reflection.

The recovery of undeservedly “forgotten women artists” is more than merely an exercise in canon expansion or revisionist history. From curatorial and scholarly perspectives, it appeals to those of us (surely I’m not alone here) who harbour a secret persona as super sleuth detective, who enjoy tracking down artworks hidden from public sight for many years, sifting through the minutiae of historical evidence and giving vent to righteous feminist indignation. And from the perspectives of readers and gallery goers these works enable revisiting past eras with fresh eyes so that well curated retrospectives such as this can be revelatory. Bessie Davidson is a textbook case: a dedicated professional painter, she quickly moved beyond mere academic facility to pursue a modern Impressionist vision that won her critical acclaim in Paris where she hosted a weekly salon and became a significant advocate and organiser of women artists as vice-president of La Société Femmes Artistes Modernes as well as an associate, member and secretary of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and a founding member of the Société Nationale Indépendantes. Firmly established in Parisian art circles, she was nonetheless largely neglected in Australia and even now is poorly represented here in public collections with only the National Gallery of Art and Art Gallery of South Australia holding examples of her work. The reason for this neglect is not simply her absence from Australia for most of her career but almost certainly Davidson’s refusal to toe the chauvinist national line, rejecting calls to forge a great “Australian School” and instead choosing to express herself in the lingua franca of French modernism.

The precise form this modernism took was not what is commonly considered as avant-garde—despite the exhibition title—but rather an Impressionist investigation into light. Davidson paid particular attention to the behaviour of colour under different lights, so that her white tablecloths are never white but rather a bold patchwork of yellow, blue and umber. Large windows such as that found in An interior, c. 1920, flood rooms with natural light and allow for a play of shadow and reflected colour, while plein air landscape sketches and figure studies such as Fillette au perrouquet (Little girl with parrot), 1913, Lecture au jardin (Reading in the garden), 1930s, and La robe jaune (The yellow dress), 1931, employ raking light to model forms with colour rather than tone. In the 1930s Stella Bowen, who took an apartment in Montparnasse above Davidson’s at 18 Rue Boissonade, referred to her neighbour as ‘the old Australian impressionist’—reflecting not only cross-generational contact but also the simple truth that Impressionism was still one of a number of viable aesthetic positions in inter-bellum Paris. Later that decade Davidson increasingly adopted a Cézannesque Post-Impressionism in her exploration of form: objects, figures and backgrounds loosely knitted together in impasto patches of colour, often applied with the knife and distilled to their simplest forms.

Davidson’s repertoire of subjects was typical of many other women artists of her generation and earlier: portraits of female friends, mothers with young children, domestic interiors, still life paintings, flower paintings and small-scaled landscape sketches. Presumably these were the subjects most readily available to her, as well as most saleable, but they also allowed her to demonstrate her modernity through painterly technique, as mentioned above, and composition. Consider, for instance, Le livre vert (The green book), 1912, thought to be a portrait of Margaret Preston in a fashionably aesthetic interior that includes velvet chaise lounge, samovar and a single stemmed pink rose—possibly a double entendre allusion to Preston’s middle name, Rose, by which she was known. The sitter leans forward on the edge of her couch, her unfocused gaze contemplative, one finger (sans ring) slipped inside her book to mark the page as she pauses in her reading. Her sprigged white muslin dress carries a multitude of cultural meanings: an icon of French femininity, evocative of innocence and modesty, it also provoked intense furore four decades previously in Manet’s Le Repos: Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1870-71, owing to the sensual casualness and indolence of the sitter (not to mention its negation of Morisot as active agent and artistic rival). Davidson’s sitter is certainly feminine, but she is also independent, unencumbered and enjoys a life of the mind and emotions. The swept up auburn hair and slightly flushed cheeks heighten this impression. What is the eponymous book? A Parisian romance? A technical painting treatise? In true “subject picture” style we are left guessing.

In similar vein, Interieur (possibly a work titled Jour de soleil), 1925, is more than simply a boudoir scene. The unmade bed and the gown draped over a chair speak of intimacy, underscored by the female life study framed on the wall above the bed while also presenting a subject bathed in morning light from a window seen partially reflected in an over-mantle mirror along with a woman’s head—probably Davidson’s long-term companion, Marguerite Le Roy.

Where the portraits and interiors are allusive and visually seductive, the still life paintings belong to the more prosaic and haptic world of the tea table and the sitting room. We imagine the cool smooth glaze of a ceramic tureen contrasting with the slightly rumpled heft of the linen tablecloth (Still life with pears, 1930s).

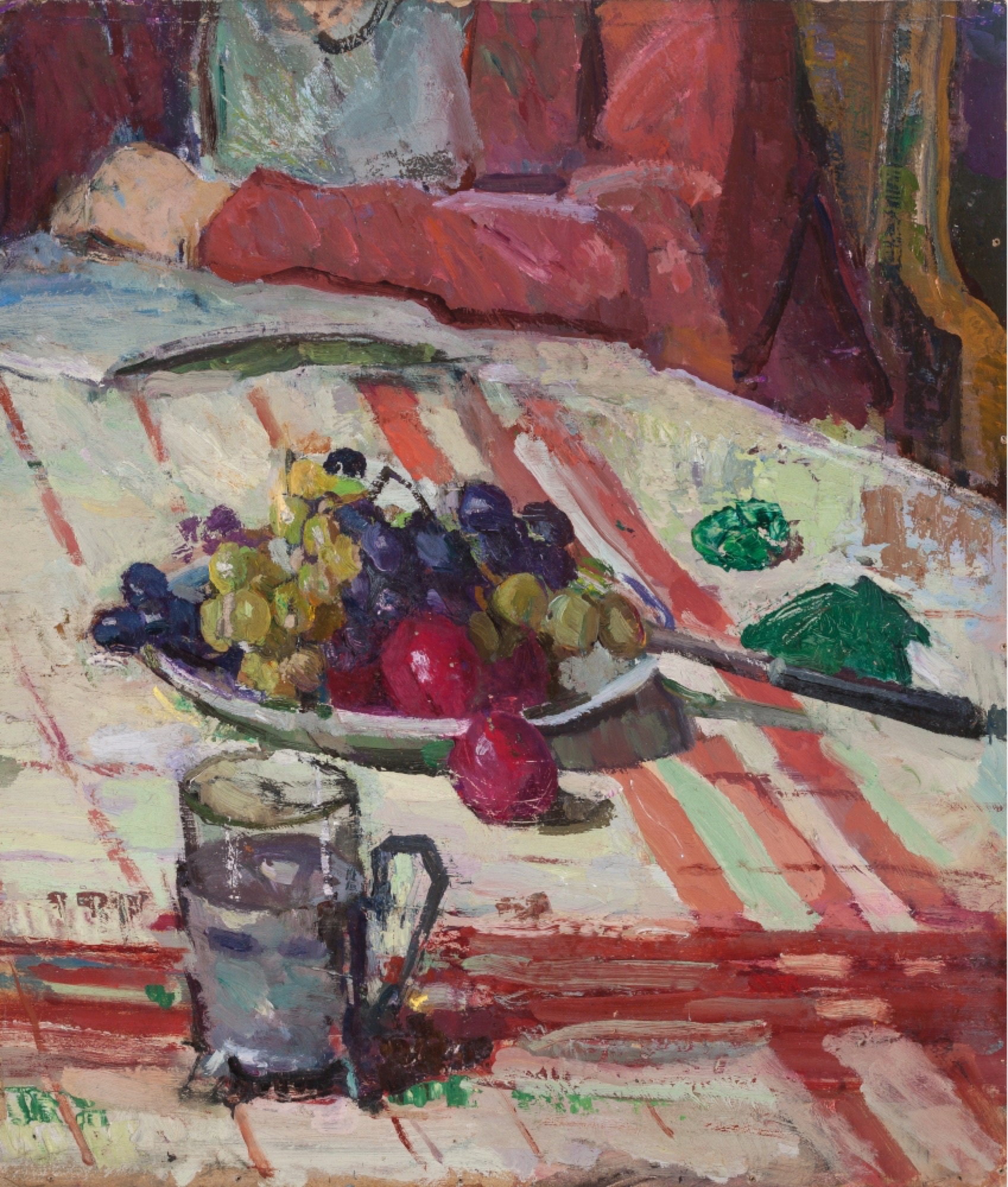

We feel invited to warm our hands around an elegant silver tea glass holder before reaching out for the fruit knife that balances invitingly a dish of grapes and plums (Still life with a bowl of fruit, c. 1935). In the same work a homely French striped tablecloth offsets any sense of formality that the elegant utensils might suggest while, in the background, the startlingly cropped figure of a woman reading at the table adds to the intimiste sense of domestic informality.

Other works appeal to the sense of taste. An arrangement of melon and plums with a narrow carafe of what looks to be a dessert wine speaks of natural sweetness and hospitality while a partially obscured object to the right is possibly a wooden salt box, the contents of which contrast with the sweetness of fruit and wine (Still life with fruits and a carafe, 1930s). Evidently Davidson was alert to the devices of the seventeenth-century Dutch still life painters, as well as the warm rustic naturalism of Chardin.

Her flower paintings share a similarly earthy palette. Where many of her contemporaries adopted high-keyed colours infused with white, in keeping with the moderne, Davidson’s flowers belong to the earth. Brown tones from the unprimed boards (seemingly her preferred support) unite flowers, vases, fruits, tables and backgrounds, and speak of gardens and terre glimpsed through open windows. Rarely are hothouse flowers featured; instead we find native mimosa mixed with cottage garden flowers: anemones, hellebores, wallflowers, poppies, roses, clematis, magnolia, Arum lilies, gladioli, irises and humble geranium. These are arranged informally in simple glass vases or brown-glazed pottery jugs and held in place by thick impasto backgrounds of creams, terracottas and dark browns. Heavy use of the palette knife ties objects and backgrounds together. An exception to this general rule is an arrangement of bluebells and crimson bell-shaped flowers (possibly hollyhocks) in a Faience jug, decorated with lemons and a floral motif, in which the colour of the flowers positively pops against an apple green and lime background (Bouquet, c. 1945). The approximate date, at the end of the war, may help explain the unusually joyous burst of colour.

Given the virtual nature of my experience of this exhibition, I’m hesitant about commenting on Smart’s immersive video installation. From excerpts, stills and interviews I gather it involved two dancers whose performance aimed at embodying or calling forth the physical presence of Davidson and her friend, teacher and—Smart surmises—erstwhile lover, Preston. The performance takes place in a large warehouse filled with easels that not only signify the two painters but also act as proxies for other figures while morphologically evoking the Eiffel Tower. Lengths of different coloured gingham fabric are suspended from the ceiling and repeated in the dancers’ flowing skirts, continuing Smart’s long-term engagement with this particularly feminine take on the modernist grid. The dancers likewise represent a point on a lineage that stretches back to the Ballets Russes, tying together avant-garde dance with Russian Constructivist painting through the dual mediums of human bodies and gingham fabric. The physical simpatico the dancers evoke, and the floating fabrics they move through, share with Davidson a rich sensuality. In this way Smart interleaves years of artistic research with her personal narrative and sense of connection with Davidson, who, from within her own family, provided an invaluable model of what a determined artist could achieve should she persist with her ambitions and ideals.

Jane Eckett is a postdoctoral research associate in art history at the University of Melbourne and freelance curator.