Katherine Botten, Before Christ

Emily Kostos

pinker now, a scarf

gestures décolletage

attachment style in fashion

for the people outside

tears find it

change the feel but not the pattern

— from Eva Birch, “Love Object,” Verge 2021

A sixth-century Scythian monk devised the Anno Domini (AD) dating system—a system orientated around the birth of Jesus. Strangely, its familiar counterpart, Before Christ (BC), developed more slowly and was not used widely until the late eighteenth century (except for occasional instances). This sanctified yet jocular dating system (which is still in standard use in Australian public schools) is the title of Naarm-based artist Katherine Botten’s recent solo show at Cathedral Cabinet—a gallery space occupying a former 1920s shopfront on the ground floor of the Nicholas Building. Situated in the Cathedral Arcade and annexed to Cathedral Coffee, quaker chairs and charismatic genteel drinking pét-nats are often scattered outside. Curated by artist Tommaso Nervegna-Reed, the gallery was co-founded with curator Emma Nixon (the late John Nixon’s daughter) and artist Casper Connolly. The gallery’s logo—designed by Connolly and Jasper Jordan-Lang—has the same Victorian gothic sensibility as the arcade: two letter Cs in old English typeface are cased within an apple that brings to mind a Rider Waite tarot deck or Scopa playing cards.

Nervegna-Reed first met Botten at the smoking corner at Monash University’s Caulfield campus during the depths of the Covid-19 pandemic (he also tells me that he opened Cache Gallery earlier this month, which Botten will be showing at from mid-March this year). Nervegna-Reed saw Botten’s “Qigong” collages on Instagram in December of last year: repetitions of stove burners, Qantas planes, stars, and Indian deities (coin frottages and a swastika feature too). An unexpected gap in scheduling meant that Botten had five days to prepare for the show. There is something noteworthy about a time restraint—a particular containment that lends itself to spontaneity and chance. Unlike Botten’s 2023 Freedom show at Hyacinth, which was endowed with more lengthy execution and consideration, Before Christ has a confident amateurism: slapstick with a scepticism of proficiency.

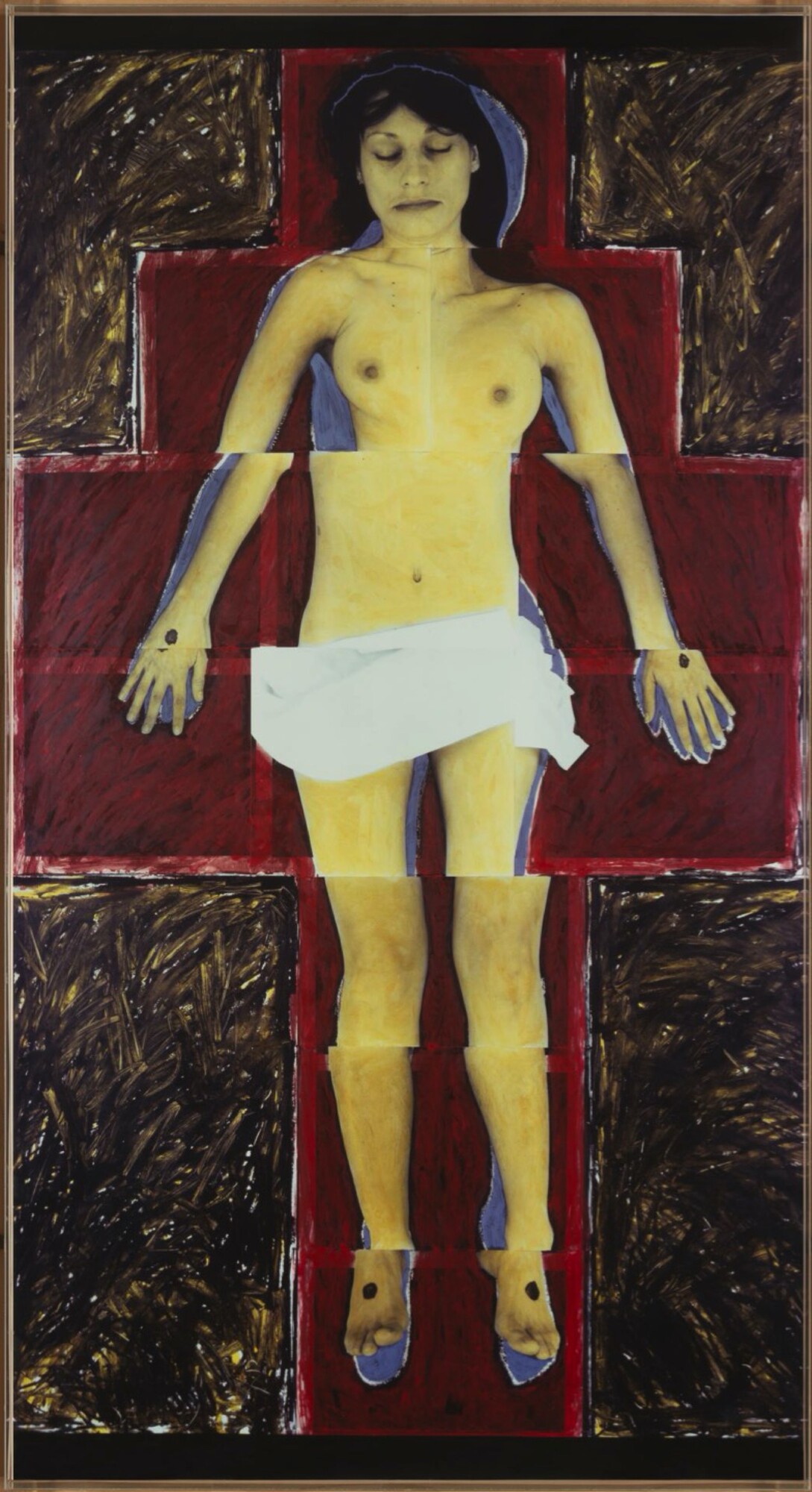

Botten’s Cathedral work is a series of five butchers-paper body tracings (presumedly the artist’s) that were draped from the gallery’s top horizontal window frame. Interestingly, this number corresponds with the number of days Botten had to prepare—possibly an unconscious meditation on time and somatic process. The works are reminiscent of East Asian hanging scrolls, body-mapping activities, and child craft. As an art therapist, I am reminded of children squirming on floors as textas outline their contours—an exercise in proprioception and intersubjective exploration. Australian artist Julie Rrap’s Christ (1984)—part of her photographic series Persona and Shadow—appropriated Edvard Munch’s paintings of women and montaged them with her own body on a crucifix. Botten’s bodies appear more like the recumbent pose of the dead, yet they equally reformulate the ways in which women and bodies are represented.

Botten’s scrolls are fastened with brown scotch tape and hung so that they press against the gallery’s glass; they read as butchers paper-stained glass windows. The biblical “Women at the Tomb” (of which the nearby Saint Patrick’s Cathedral has a version) are re-appropriated with their own energetic anatomy: the interiors of Botten’s bodies are replete with their own medley of codes and semiotic forms. Botten tells me that windows have long been part of her practice. Her last window work was featured in a 2023 group exhibition, Contradiction in Terms, at Yesterday Gallery—a 1970s first-floor apartment-cum-gallery in Naarm’s affluent inner-east. Established and curated by artist Andrew Nille, the Hawthorn gallery slots in somewhere between Melbourne’s conglomerate of house galleries (Savage Garden, Asbestos, and the erstwhile Guzzler and Meow2). The first of two exhibitions held at the Hawthorn location, Botten’s Confusion Is Sex (2023) occupied the middle of three balcony windows in the larger gallery space, set against a background of Birch trees and a powder blue sky. The title references Sonic Youth’s 1983 album; their low-fi, minimalist lyrics and musicality are encompassed in the work’s material sensibility and looming absence. A ghost-like figure reminiscent of a hollowed out Baymax from Disney’s Big Hero 6 or a chalk outline on bitumen from a 1960s crime scene is demarcated by a mash-up of Australian wool, glue, and scotch tape. While Botten is slightly taller than me, the body’s 172-centimetre height is precisely the same as mine. Standing directly in front of the silhouette makes it inviting for projection: the emptiness is both beguiling and persecutory. Is this lack of a cohesive self the despair of a cluster B personality disorder? Codependent enmeshment? Identity diffusion in which the self seeps out and fuses with whatever surrounds it? Leaving the gallery space last year, I recall a lingering presence in the form of an after-image.

It is quarter past ten on a Wednesday morning in January and raining—storms and thunder are predicted. I perch next to two older men with American accents and awkwardly manoeuvre beside them to get a closer look at Botten’s work (it is partly concealed by their posturing). There’s a flush of petrichor—an earthy perfume made of geosmin and plant oils—mixed with the distinct smell of subway sandwiches and nicotine. I choose to read the work dextrosinistral, beginning with the blue body to the far right. Two rectangles of cellophane are pasted onto butchers paper. The cellophane’s gridded creases hint at its double life as packaging, as do its jagged edges that suggest rushed scissoring and kindergarten craft. There is the faint outline of a body over the top: a fragmentary form floating in the ether. This blue form could be read as an ironic pastiche of modernist abstraction—Botten’s spontaneity parodying their hard-edged precision. Compared to the other four bodies, the blue one seems flaccid and dead. I read the second and third butchers paper bodies as less ghost-like and in a constant state of becoming, spurred on by the reinvention required by neoliberalism and an alchemical process of spiritual development.

Butchers paper body two has an alfoil head casing, evocative of hairdressing culture (foil is used in hair treatment to process bleach faster due to its heat conduction) as well as the trend of the “tin foil hat”: the stereotyped protective shield of the mentally unwell to ward off mind control and invisible forces. At the heart of this foil-headed body is a mandala-esque configuration of shells and pearls. This location is also the middle dantian—the seat of vital energy or our “life force” in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Botten is a daily practitioner of Qigong: an energetic practice involving meditation, breathwork, and movement, focused on balancing qi in the body. There is a lingering sense of the body being held together and repaired—both materially and spiritually. Three different types of tape feature throughout the work: packaging tape, band-aids, and cloth tape. Tape has its origins in healing—it was first developed by a nineteenth-century surgeon who used a rubber adhesive to join strips of fabric together. A band-aid on the head of body three is like a quick-fix to stop the blood flow—a measly ten-session, partly-rebatable course of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy through our underfunded Medicare system—but also the first move towards repair and healing.

The band-aid is accompanied by low-res photographic images of bushfires and water buckets (some are still overlaid with copyright branding) pasted along the body’s midline or “centre meridian.” It’s like the body has become a pseudo-archive for Australia’s bushfire histories, as well as psychic cleansing. In a 2014 interview with psychoanalyst, poet, and writer Eva Birch, Botten spoke of growing up in Adelaide next to a conservation park, with gum trees and Australian landscapes representing calm and emotional release. Botten uses the word “purification” on several occasions when discussing the bushfire images with me. It’s hard to know if I am looking at documentation of controlled burning—maintaining the landscape and encouraging new growth—or a blurry recollection of Black Saturday. In any case, the sixteen bushfire images and fourteen water buckets suggest a lack and cleansing to address that lack. The left hand of body three clutches an aged necklace with a pendant reading “13.” The chain coils in the gesture of the treble clef. Big Star’s 1970s song and Catherine Hardwicke’s 2003 film Thirteen come to mind. Hardwicke’s Thirteen is the shadow side of The O.C.—early adolescents seeking to have their attachment needs met through substance use, trauma bonding, and sex. Loosely based on the protagonist Nikki Reed’s own adolescence, there is a thread of the same distress that permeates Botten’s third and fourth bodies. In body four, repeated stove-burner images are pasted on the surface of a painted butchers paper body (this time closer to the lower centre dantian). Slashes of black, red, and yellow paint reverberate in the burners’ iridescent yet low-res flumes: a heat map for intra-psychic relations. Botten’s quintessential gum leaves are pasted on top of the burners, as is a single eagle feather. Like the shells and pearls, these leaves and feather are not subjected to the wind, water, and sun: they all exist in a different temporality. This temporality could be read as schizoid: fragmentary spaces between vitality and illness, physical and virtual, elegiac destruction, and purification.

The body farthest to the left is a saffron yellow one, replete with a black aura. The body has three orb-like forms that correspond to the central Qi meridians. They bear evidence of reworkings and layers: each orb has a small, red treble clef painted atop Botten’s recognisable, intertwined hands. Botten’s practice is characterised by familiar signifiers and her own referentiality: swastikas, gum leaves, stars, landscapes, windows, and treble clefs. They are, among other things, an attempt to construct a personal archive—one that continues to unfurl within itself. Writer, editor, and art historian Cameron Hurst’s review of Botten’s 2022 Freedom show spoke to Botten’s treble clefs as both ominous and “talismanic—as though ‘music’ acts as a protector, an entity that stands between overwhelming subjectivity and the external world.” The ligature of the treble clef began as primitive neumes: dashes and dots used by eleventh-century Benedictine monks for liturgical texts. The exhibition poster for Before Christ features a dated “entry” sign—one you might find at the entrance of a nineties medical clinic or Centrelink office—along with a treble clef and two broken windows. As the highest musical register, I read the treble as a portal that may surreptitiously let us in. Like staring directly into the sun—a large blinding one—only those brave enough to completely submit will understand how to enter (and exit when required).

Emily Kostos is an art therapist, multi-discliplinary artist and writer based in Naarm/Melbourne.