Barbara Campbell—ex avibus

Camille Orel

Barbara Campbell wants us to follow the birds. Her current show at the Geelong Gallery, ex avibus, retraces the global migratory patterns of wading shorebirds—a new instalment in her longstanding commitment to reconceptualise the (im)possibilities of artistic expression. In this exhibition, these possibilities are doubly explored through an emphasis on the agency of the gallery visitor who, admitted into Campbell’s constructed ebb and flow of a natural homing route, experiences the shorebird’s journey as they walk through the gallery.

Despite ex avibus’s emphasis upon a forward trajectory, I experience the exhibition somewhat back to front. Not having been to the Geelong Gallery for a couple of years, I decide to walk to the rear of the building and stop by the permanent collection before visiting Campbell’s exhibit. Swooning over the mammoth Juan Davila and Fredrick McCubbin paintings that share a name—A Bush Burial—I realise that I have already had my first encounter with Campbell’s show. Displayed directly below McCubbin’s renowned work sits a cabinet filled with several minimal watercolour paintings placed atop a two-dimensional photogram print of an Eastern Curlew shorebird specimen. Ok, duh, I get it now! The show is sprawling throughout the entire gallery so as to emulate the journey of shorebirds migrating south. Now I’m on the right track—kind of (I’m still walking the wrong way).

The paintings, a component of Campbell’s Soft Part Colours (2015) series, are chromatic studies of the “soft parts” (that is, everything except the feathers) of the Eastern Curlew shorebird. They document what Campbell describes in the accompanying artist statement as the “fugitive” colours of the birds: those colours that fade swiftly after death. Displayed under a glass cabinet, the watercolours oscillate between organic blots, fades and smudges before shifting to horizontal linearity and geometric form. Paired with the photogram silhouette of the Numenius Madagascariensis (2022) specimen below, the display is reminiscent of cataloguing practices common in the empirical sciences. This approach is splintered by Campbell’s divergent artistic impulse to capture the fleeting by documenting and archiving (and hence reifying) colours that can nonetheless only exist temporarily in the natural world.

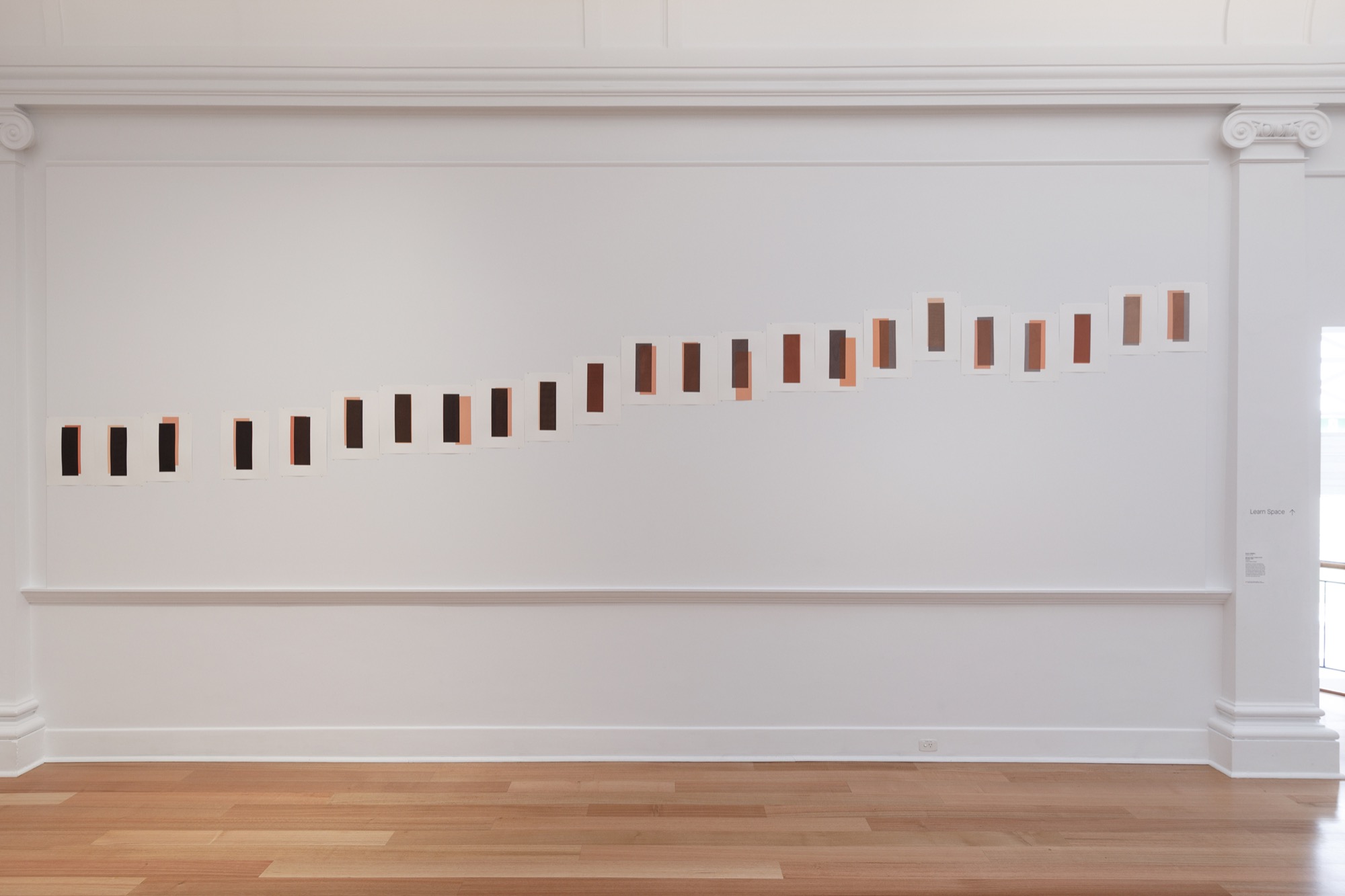

This tension between the permanent and impermanent can be followed across to the other side of the room, where a collection of Campbell’s screenprints traverses up the gallery wall. The sequence of twenty-two A3 size prints, also a part of her Soft Part Colours (2018) series, climb diagonally upward. They are displayed like art with a capital A, as opposed to the flat lying watercolour “specimens” on the other side of the gallery. The charcoal top layer of the two-tone geometric screenprints progressively loses opacity the further up the wall the prints get, revealing the different shades of peach pinks beneath that correspond with the fading “soft parts” of the Eastern Curlew shorebirds. While there seems to be less of a focus on the empirical as an aesthetic, it continues to underpin the composition of the prints. Between the two pieces from the Soft Part Colours series, Campbell ensures a formal unity in their shared rectangularity and hue that guides the viewer from one work to the other, moving around the gallery’s existing artworks.

Visually, I find the most striking aspect of this series to be how these colours re-pronounce themselves throughout the accompanying permanent collection. The blushing clouds of Eugene von Guérard’s View of Geelong (1856) become more conspicuous, as do the soft reds in the rocky foreground and the shadowed wagon in McCubbin’s aforementioned A Bush Burial (1890). Perhaps this is the moment where the question that Campbell has continued to ask throughout this ongoing project, as articulated in her PhD thesis, is the closest to an answer—“how do birds lead humans to perform other versions of humanness?” By this I mean that, here, I am made to reconsider the formal properties of these pre-existing artworks only after following the pattern of a shorebird’s migration and experiencing Campbell’s artistic output as a result of that migration.

Looking again at the artistic statement attached to this work, it is interesting to note that these screenprints are not the result of Campbell’s own visual impression of shorebirds, but a response to verbal descriptions given by the Victorian Wader Study Group. Walking through the gallery, we are not following the migratory patterns of shorebirds but, instead, Campbell’s artistic projection of a verbal description of that migratory pattern, produced by humans. Interestingly, this means that the exhibition is already in a position twice removed from the subject from which it takes inspiration for both its method and content. Furthermore, my experience in the gallery (and indeed this review which will predominantly be read in Naarm/Melbourne) then even further extends the destinations of this migratory pattern.

This chain of transmission is clear again in the video work, Chongming Dao Boustrophedon (2016), which plays discreetly on a monitor in the centre of the space dedicated to Geelong Gallery’s more contemporary permanent collection. Not dissimilar to the composition of the Soft Part Colours cabinet display, this work again bespeaks methods of empirical observation, documenting the locals and field scientists at the mouth of the Yangtze River who witness the shorebirds passing by. What this video makes clear, together with both works from the Soft Part Colours series, is that the migration patterns of these shorebirds must be siphoned through some other medium before their presence in Campbell’s artwork can successfully pattern the viewer and the shorebirds together in the gallery.

If Campbell’s sprawling exhibition is remarkable for the ways in which it transfigures the Geelong Gallery and its permanent collection—which includes some of the most distinguished pictures in the Australian canon—it is also reminiscent of a peculiarly romantic failure of the imagination. Campbell’s attempt to comprehend or explicate the influence of, in her own words, “other-than-human” agents on human subjectivity and its projections can never be successful without repeating the logic of that influence from the privileged perspective of human intervention. That is, at the exact moment you attempt to recognise the existence and influence of anything outside anthropocentrism in art, you necessarily envelop it into a grid of human intelligibility. Apparent throughout this exhibition is Campbell’s cognisance to this frustration and it is continually re-addressed and transformed throughout her artistic project.

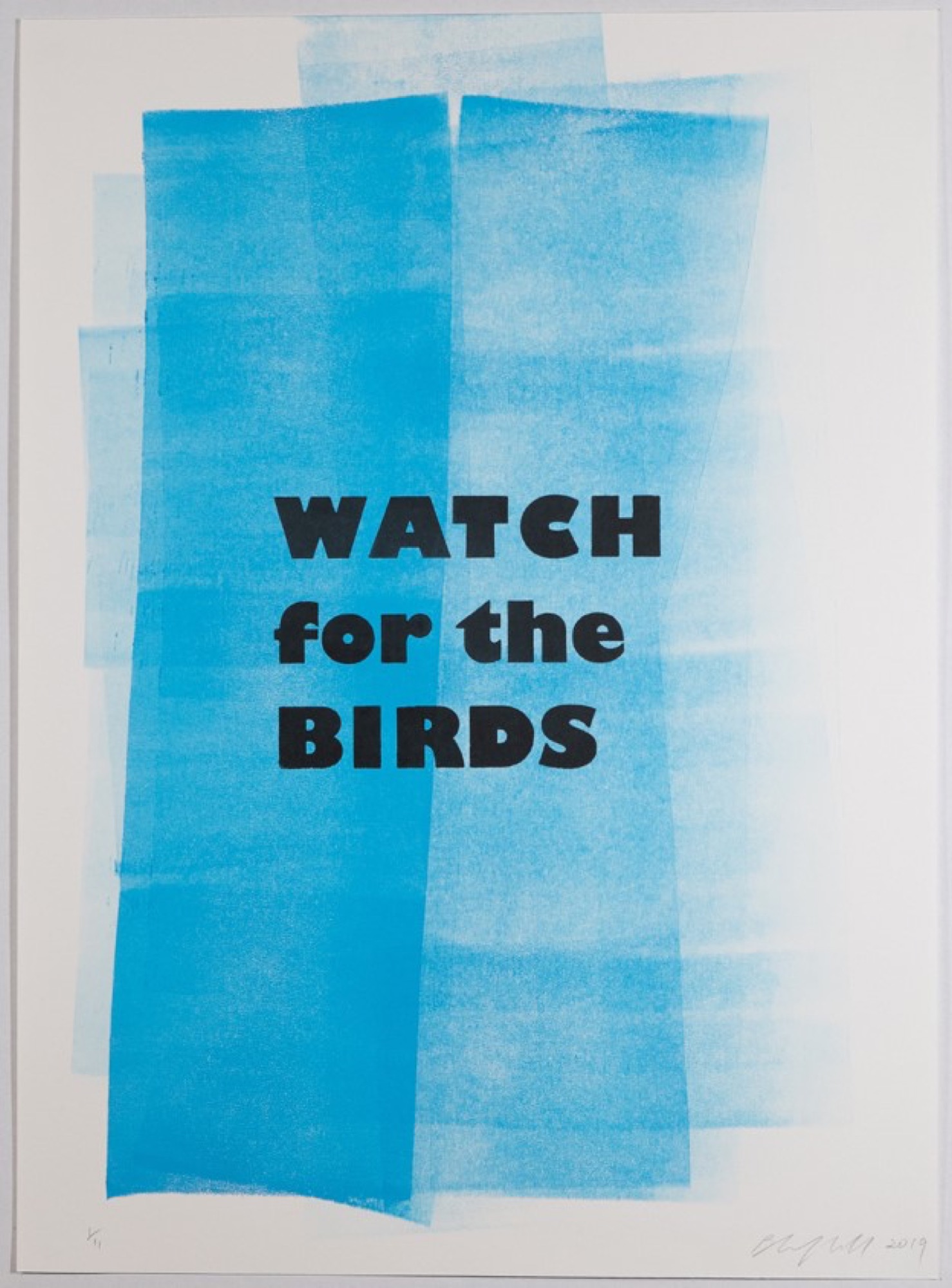

An example would be the small letterpress print, Watch For The Birds (2016), that marks the entrance to the exhibition. If I had walked through the show the “right” way, this unassuming piece that spells out “WATCH for the BIRDS” would have greeted me on my way in. The use of the letterpress immediately appeals to the historical imbrication of knowledge, technology and transmission. More specifically however, the phrase itself signals a recalibration of the shorebird’s flightpath (which, as this piece sits just outside the first installation space, is yet to be encountered) that centres a human perspective. In a gallery, one cannot simply “WATCH BIRDS”—guidance is needed. In this case, the intervention is as simple as the insertion of the word “for”. The preposition introduces intentionality. And that intentionality for the viewer informs them of their own role within the exhibition. Follow their route and the shorebirds will appear. So, too, will the art…

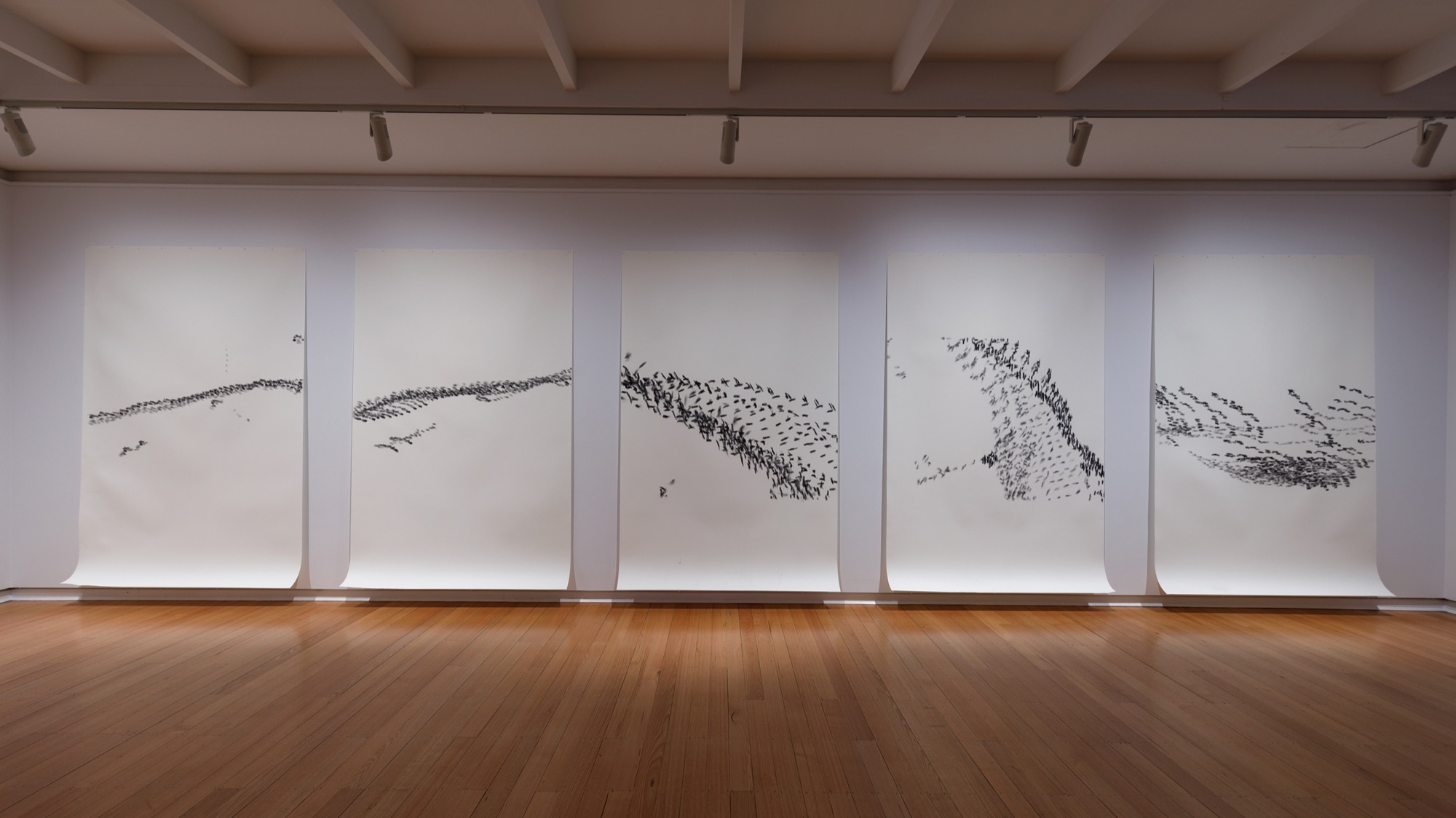

As I walk into the main exhibition gallery (this space is dedicated solely to ex avibus) the relation between the verbal and textual is established as the visual register of the letterpress print is transformed into an auditory experience. The sound installation, Well There You Are (2015), contains concealed motion sensors that sit vis-à-vis five wall-length charcoaled sketches on either side of the narrow room. The title of each drawing corresponds to the verbal expressions that sound off as you walk past the sensors, featuring the voice of Gordon Ramsay (not the chef), Campbell’s bird watching neighbour in Rosebuck Bay.

I roam clockwise around the room. But, having walked through the wrong entryway, my circumnavigation leaves the motion sensors untriggered, meaning I totally miss the auditory component of the installation. Only after circling back—and (finally) commencing Campbell’s anticipated spatial migration—am I intercepted by a muffled chorus of migrating shorebirds chirping under Ramsay’s commentary.

For once, it seems, doing what I’m told, I’m guided through the room by a voice that Campbell describes as the “fortuitous soundtrack…of departing Godwits (shorebirds) in migration formation”. I travel alongside the large-scale drawings whose charcoal markings flutter across the pages. The composition of these works really does emulate a coordinated flock of birds sweeping across a skyscape, with the direction of the charcoal strokes and smudges shifting across each sheet of paper. However, it is Ramsay’s responses to this murmuration that become necessary to the viewer’s concurrent movements by verbally confirming the migratory changes of the flock.

By the time I get to the doorway that opens into the rest of the gallery, I turn back and take in the room in its entirety. On the opposite wall the video work, also titled Well There You Are (2015), plays on a loop. There, multiple Barbara Campbells add charcoal impressions to a sheet of paper, gradually building up the flock in a seemingly choreographed harmony that syncs up with Ramsay’s voice as it is triggered as another visitor walks through the room. It looks like they’re headed in the right direction. It doesn’t really matter. As W. B. Yeats had it, “they had changed their throats and had the throats of birds”. Walking out of the gallery into the rainy streets of Geelong, the shorebird’s flight continues.

Camille Orel is a writer living in Naarm/ Melbourne