Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion

Matthew Linde

I was staying with Mona Bismarck in Capri when the news came. I was downstairs, dressed for dinner, having a drink. Consuelo Crespi telephoned me from Rome, saying it had just come over the radio that Balenciaga had closed his doors forever that afternoon, and that he'd never open them again. Mona didn't come out of her room for three days. I mean, she went into a complete…I mean, it was the end of a certain part of her life!

– Diana Vreeland on Mona von Bismarck in D.V.

Twentieth-century couture is immortalised by three masters: Chanel, Vionnet and Balenciaga. But only one is deemed the “couturiers' couturier”, or so the platitude goes. The title of Bendigo Art Gallery's latest fashion exhibition, Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion, on tour from London's V&A Museum, does little to dissuade this grand narrative. Shaping Fashion not only suggests an allegory for sculpting cloth but also the revolutionary shaping of history itself.

In 1973, Diana Vreeland opened her inaugural exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute, The World of Balenciaga. An image captured during install depicts the impresario preparing Balenciaga's now canonised one-seam coat (1961). Staged atop a plinth, appearing as grand necromancer, her hands contour the coat as if levitating its sculptural cadaver. While packing detritus, undecided shoes and background ensembles clutter the image; the coat is seen autonomously, afloat a headless bust mannequin, erected by an indiscernible metal stand.

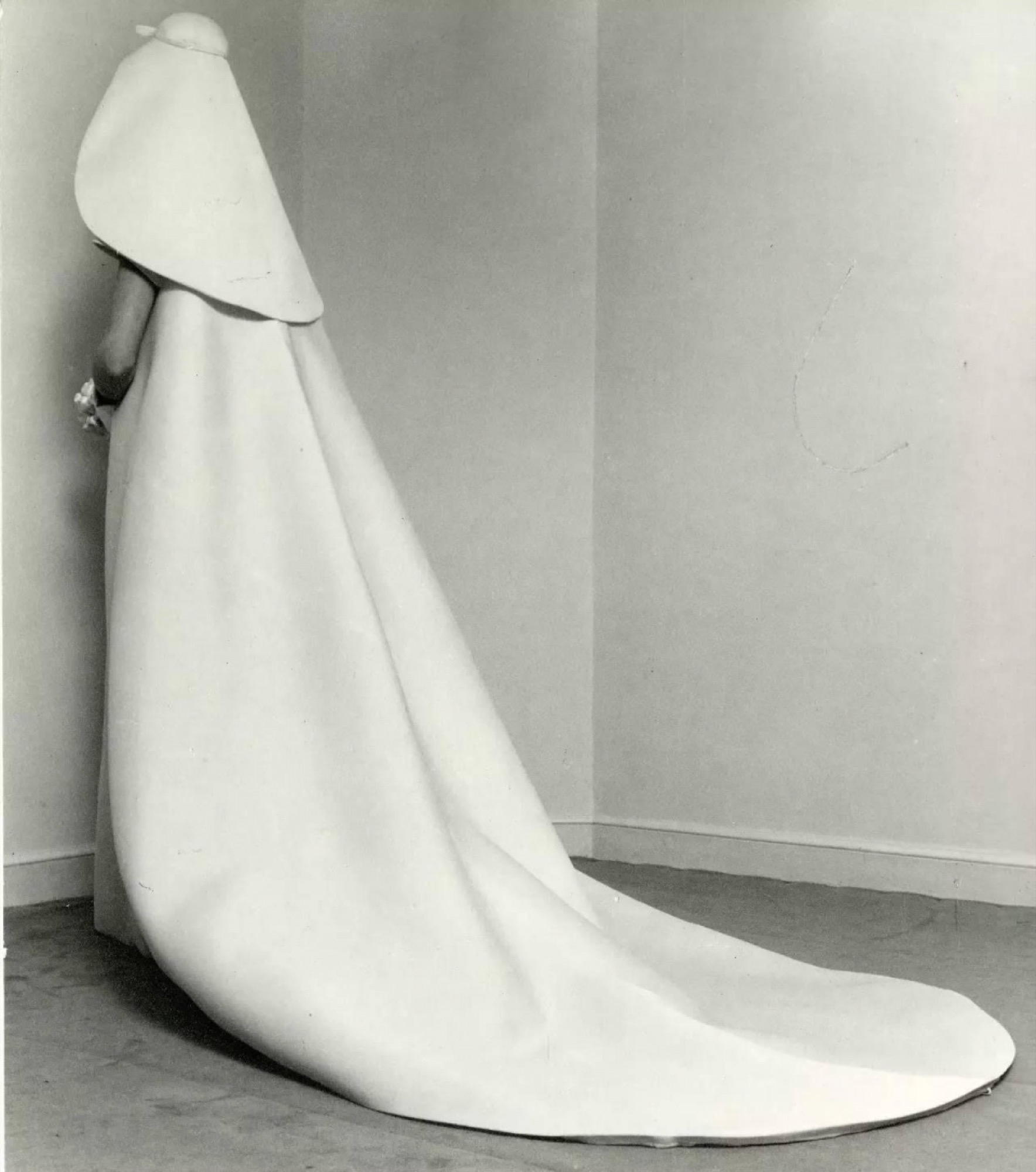

Ghostly austere, the one-seam coat exemplifies the apogee of Spanish-born Cristóbal Balenciaga's 360-degree approach to design. Known for his minimal “purist” shapes, he effaced ornate decoration and abandoned nineteenth-century construction techniques to innovate staggering new forms through experimental cutting, darting and nominal seaming. Made by one piece of fabric with a single seam running the underarms across the yoke line, the coat cocoons the body in a convex husk engineered by no less than twenty darts. Catalysing a modernist sartorial grammar for the post-war period that developed until the late 1960s, Balenciaga has been touted as the progenitor of numerous silhouettes and lines that defied the human figure. And while it's silly to declaim Balenciaga “redesigned” the woman's body, the exhibition's conceit of Shaping Fashion proposes a profound puzzle: the silhouette's innate ambivalence for the human form.

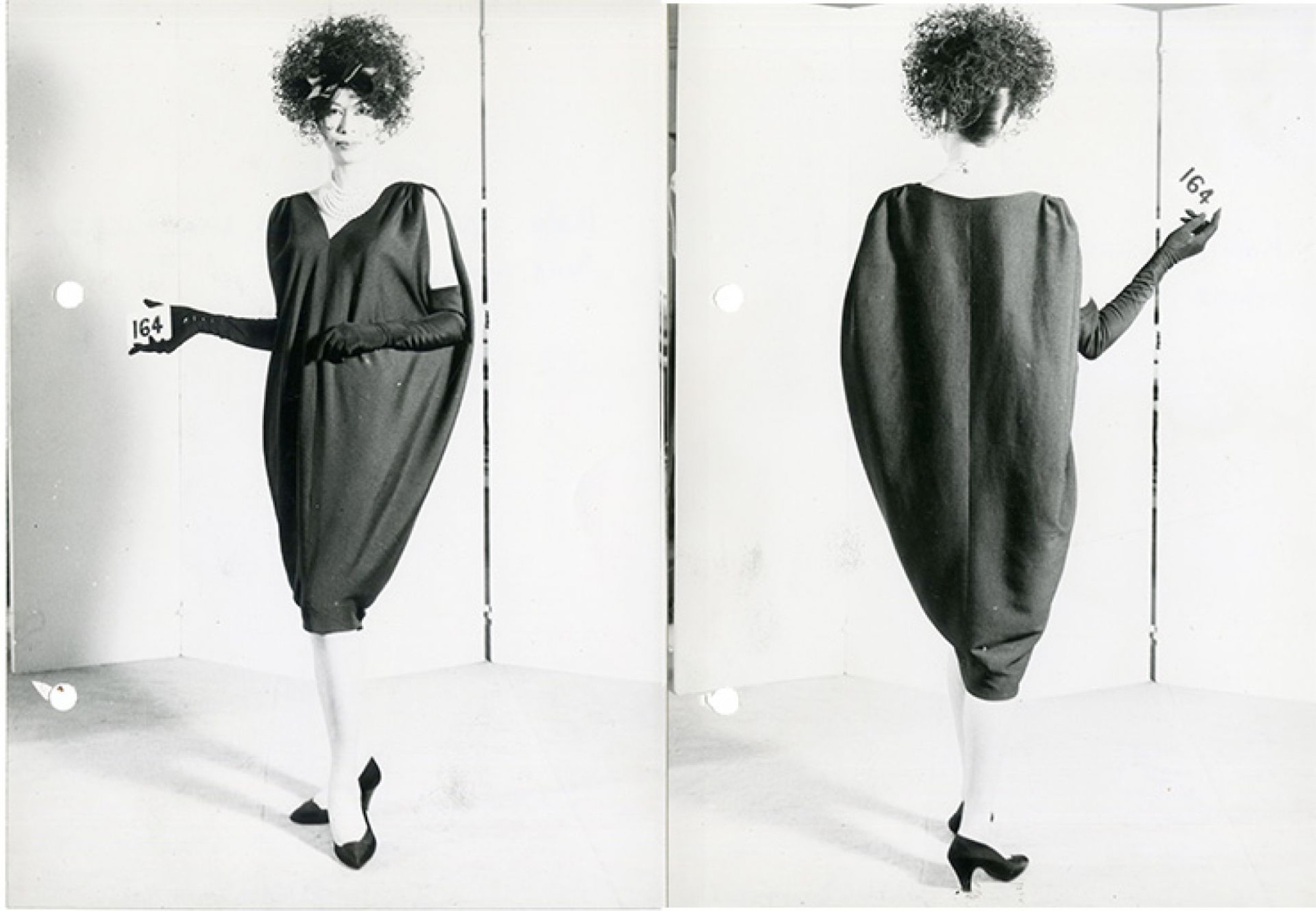

Opening his couture house in 1937, it wasn't until Christian Dior's New Look emerged in 1947—a kind of BC/AD myth-making timestamp in fashion history—that Balenciaga gained his polemical position. During this time of post-sumptuary feminine recuperation, when Dior's hailed hourglass figure saw waists radically synched in, Balenciaga debuted his controversial barrel line: a waistless ovate-moulded suit that hunched volume across the back and tapered at the skirt's hem. A relatively reduced look, it garnered much criticism from the fashion press, reconfiguring the body's geometry in unsightly proportions. By obliterating the waistline, it seemed Balenciaga had obliterated the very coordinates that conceived the self.

Walking through the exhibit, we learn of Balenciaga's many design milestones, more through explanatory notes than garments, leaving those less informed spatially guessing. He continued his figurative abstractions with the sweeping taffeta harem balloon dress of 1950, later developing into the balloon jacket of 1953, a spherical sleeveless bodice from which the head floated above. In 1955, he would reveal the tunic silhouette, a chemise-style tubular dress. Built as an elongated unfitted sleeveless bodice, its body gathered at a bias-rolled stand-away collar and was sewn into a dropped waistline forming a calf-length skirt.

Dramatising this line ever further, Balenciaga debuted the infamous sack dress of 1957. In one of its iterations, the silhouette was cut in wide curved lines that tapered slightly below the knee. Unadjusted by darts or belts, it hung with certainty from the shoulders, enveloping the body to create unprecedented space between garment and body, with its unknown figure regarded as profane yet utterly precipitating the mass-produced shift dress of the 1960s. The following year, the lampshade or babydoll silhouette was revealed, a lightweight fluted trapezoid dress with a low waist and flounced skirt. And so the list goes on (my personal favourite being the 1960 amphora line!)… In fact, decades before Rei Kawakubo's 1997 masterstroke Body meets Dress, Dress meets Body, Balenciaga had already exhausted half a career interrogating the strange aberration between garment and body.

How then might one exhibition represent such hefty hermeneutics? First of all, there is serious scepticism towards this mode of bought-in blockbuster, and for good reason. Although the escalation in worldwide fashion blockbusters expose the public's keen interest for the genre (in 2014 the National Gallery of Victoria became the ninth leg for Jean-Paul Gautier's retrospective as part of an international twelve-stop museum circuit), these touring hagiographies simultaneously thwart curatorial exploration and critical response. As fashion Professor Peter McNeil has written, “The reality within museums– in Australia at least– is that the curatorial commitment to sartorial fashions has declined– not been buoyed– in recent years,”, suggesting that the increased dedication to the blockbuster's triumphalism has outweighed the need to build both “collections and the careers of curators”. Under the directorship of Karen Quinlan and now Jessica Bridgfoot, Bendigo Art Gallery offers a possible alternative to this narrative. For if museums aspire to be assemblies of market interactions, then at least pessimistically it's productive to reroute such a blockbuster to this regional town.

However, more than just providing key economic stimulus for Bendigo, the gallery's shows generate unique community dialogue and exposure with the work, and because of its smaller scale and strictures could hopefully even spark new curatorial experimentation unexplored by goliaths like the V&A or NGV.

Amongst the various garment highlights, the most astounding was to finally encounter the evening gown and cape (1967). Carrying all the motifs of his most iconic ensemble, wedding dress (1967), an impossibly costly artefact to have had mounted here, it exudes Balenciaga's ecclesiastical tendencies. Miming the shapes of clergy vestments (mozetta and soutane), this sweeping black sleeveless dress with mirrored cape both demonstrates Cristóbal's expert cutting, its sculptural form achieved by a single centre-back seam, as it also recounts the famous clientele he garnered. Made for Gloria Guinness, often cited in International Best Dressed lists, his other devotees included Pauline de Rothschild, Ava Gardner and Mona von Bismarck, who, as one of the world's richest women, reportedly bought one hundred and fifty pieces from a single season.

The raciest moment however, was to be found in video: a small projected montage of several salon shows. Here we see his spectral figures in flight, presented in hushed solemnity, representing the antithesis of Christian Dior's exuberantly graceful shows, with their serious attitude imbuing the designer's own taciturn character and ascetic work ethic. In discussing Balenciaga's tense performances, modelled by “monster mannequins”, Ernestine Carter, fashion editor of The Times of London, wrote of one prolific Balenciaga model, Colette:

with her Dracula walk, her big head low like a bull ready charge, her shoulders hunched down, her arms swinging low, and a look of almost violent hatred on her face as she passed, concealing the number of the dress from the spectators.

Wrapped up in Balenciaga's religious references and monastic reverence another, perhaps stranger, magic emerges—the silhouette's psychic medium. The conundrum of the silhouette persistently troubles us: the fact that, despite our best efforts to load it with temporal significance (the 80s “power” shoulder = the new woman CEO, etc.), the silhouette's relentless proleptic mode demands that its meaning be detached and abandoned for its own self-preservation.

In Elizabeth Wilson's archaeological Adorned in Dreams, the author refers to René König's psychoanalytical account, seeing its “perpetual mutability, its 'death wish', as a manic defence against the human reality of the changing body, against ageing and death.” If the body is dangerously ambiguous, the silhouette serves to capture the volatile self in the certainty of its image. Many have also confronted the changing silhouette as axiomatically the project of modernity. Anne Hollander has charted the origin of this relationship through the advent of thirteenth-century plate armour. By mathematically mirroring the anatomical lines of the body, plating improved the functionality of its clumsy chainmail predecessor by generating its own dazzling abstraction, expressing our rationalisation of the body but only through its representation at a remove.

Then there's the truism of the commodity fetish—handy in discerning sartorial integrity, it still doesn't explain the silhouette's scriptural supremacy, which, seen on a large scale, reshapes entire historical structures as a kind of ritualistic mad rationality. Considering this dilemma back in the 1930s, Walter Benjamin became fascinated by the strange anachronistic silhouettes of his time, the Belle Époque revivalism. Benjamin's famous musings of fashion's insubstantiality to historical linear time led him to write of modernity as “the eternity of hell”. The Silhouette, as our sick collective medium, represents revolutionary change deprived of all telos.

Such visions of Balenciaga's psychic shape-shifting, I would argue, are never quite fulfilled in Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion. The most consequential disappointment was just how unbearably claustrophobic the initial vitrines were. For an exhibition devoted to the onerous idea of Shaping Fashion, tamping these mannequins into such tight containers, visually cluttered by didactics, ephemera and pokey downlights, rendered these sculptural paragons more like dusty doodads.

This was especially true of the royal tulip dress (1965), an architectonic gown featuring a curvilinear petalled line, in which a suspended panel of fabric built into the shoulders creates the illusion of monumental bloom. Here it looks just desperately inconvenient.

On the other hand, it was fantastic to see his fabric swatch books, outlining the designer's long-term collaboration with Gustav Zumsteg, a Swiss textile manufacturer, on his most signature cloth: gazar. A nubbed silk intended to imitate cotton bandage, it bestowed deep, structural folds without the need for superfluous reinforcements.

The second, bulkier arena of the exhibit covers Balenciaga's legacy, those later designers evangelized by his work. Vanguards such as Mary Quant and André Courrèges expound upon his exceptional wasitlessness, translated through novel prêt-à-porter, while there was the clever inclusion of Sybilla's green balloon dress (Spring/Summer 1987), whose undulating sculptural balloons emulate Balenciaga's free-floating caterpillar dress(1961) (not featured in the show).

While many other participants provide contemporary delight few offer actual insight into his design impact. Sure, Molly Goddard churns out the tulle babydolls season upon season, but how do they contribute to either technique or shifting corporeal ambivalences? Or there is the tenuous inclusion of celestial Disney warrior Iris van Herpen, now a typical presence for so many of these blockbusters in general, with her tormented addiction for mirrored fractals seemingly unlocking the pineal gland of any stuffy museum. Reinforcing the rather dreary claim that fashion is daringly eclectic, Balenciaga's “legacy” lacks the curatorial precision other exhibits have taken to wrestle the shifting silhouette, like Richard Martin's superbly syncopated Three Women: Madeleine Vionnet, Claire McCardell, Rei Kawakubo at the FIT Museum, New York; or Véronique Belloir's and Olivier Saillard's Balenciaga-specific Balenciaga: l'Oeuvre au Noir at the Musée Bourdelle, Paris. Both suggest less is more.

Given this unfocused trajectory, I took the liberty to target a different storyline: the house's own continued governance. After two revival attempts in 1987 and 1992, it wasn't until Nicolas Ghesquière's appointment in 1997, loved by patricians and hipsters alike, who upheaved the house from obscurity—none are ungrateful to see here his fantastically armoured PVC sliced sack dress (Autumn/Winter 2008), layered with spongy lining and bonded seams, installed with the same singular valour as Vreeland's one-seam coat. Succeeding Ghesquière was Alexander Wang, whose 3 year stint was as pitiful as Demna Gvasalia's current reign is colossal. Occasionally reinterpreting Cristóbal's deft sculptural manoeuvres, the exhibition includes Gvasalia's salient Helly Hansenski jacket (Autumn/Winter 2016), whose dart values have been merged into the zipper line so that, depending where it's fastened, the silhouette arches new volume away from the bust or back! Despite this and other cunning silhouette studies (of which warrants its own review), Denma's Balenciaga obviously plunders a different cultural junkyard to that of Cristóbal's or even Nicholas'. Thanks to the ascendency of new emerging markets, an info-supremacy society and the levelling towards meaner production, the house, mechanised through the gruesome power of its parent conglomerate Kering, has come to epitomise the memetic image of the moneyed globalised streetwear hipster; a new target much more influential than the bygone high society Madame.

This is hardly a nostalgic whinge for a lost heritage –von Bismarck has had her day—only the recognition that Balenciaga has successfully re-mastered the new conditions of sign-value circulation. Online cultures and disposable soft irony now define the house; no wonder megastar Anne Imhof is a Balenciaga associate, her libidinal malaise the leitmotif of our atomised internet age. Christian Dior's famous deification of Balenciaga as “the master of us all”, today reads deliciously Orwellian under Gvasalia's tutelage.

Neglecting to satisfy my lust for either spatial penetration or insightful comparisons, the exhibition does bare the silhouette through clues of technical striptease. The full ensemble x-ray scans by artist Nick Veasey evidence the invisible weights embedded in evening gown and cape's hem, while the calico replica of the fuchsia ballgown (1954) reveal the unfastened internal ties that would otherwise suspend its majestic pendulous hem. Interesting in terms of construction, exposing the ghost in the machine also reminded me how couture evinces an extremist mode of secularist mysticism, in which technique is bestowed with supernatural reverence. And that unlike the liturgical vestments Balenciaga so wonderfully evoked, it was the magic of beau monde materialists that encrypted his designs with divinity. Whereas other designer exhibitions mightn't need to illustrate their commercial frameworks, this show did well to outline, throughout its didactics, the patronage of socialites and royalty who equally shaped this fashion history.

If that seems an obvious observation, it was also one that spoke to me about the deeper potential of fashion's irrationality. Skim the surface and there's no dearth of highfalutin Balenciaga anecdotes. As Vreeland once remarked:

One never knew what one was going to see at a Balenciaga opening. One fainted. It was possible to blow up and die.

Easily read as rabid affirmations of consumerist culture, this fetishistic drive also points to spiritual encounters, a horizon line breaching the non-sentient world. Like the talisman of embedded weights or hidden ties, the poetic mutations of the relaxed waistline or new silhouette cannot be adequately justified by reason alone nor do they adhere to the mechanical standardisation or scientific progress of our time. To quote Elizabeth Wilson quoting Walter Benjamin, fashion accumulates within itself “the dream energy of society”, of which he felt culture had otherwise been so drained. In a world of such wholesale commodification, the Silhouette, whose inbuilt perpetual novelty renders itself the perfect capitalist gift, can also become its most ardent opponent. Delivering messianic self-implosions, Balenciaga's abstractions point to the fallibility of our collective experience, and through it we may glimpse an escape route. And, in this sense, the exhibition's ludicrous title seems almost deserved.

Matthew Linde is a fashion exhibition-maker and PhD candidate at RMIT University, School of Fashion & Textiles.