Lucina Lane and Alexandra Peters, As of hornets smoked out of their nest, 2025 (installation view). Courtesy of the artists and 1301SW

As of Hornets Smoked Out of Their Nest

Giles Fielke

Who would win: Ben Roberts-Smith or Ted Kaczynski?

It might be an obvious thing to say now, but modernism is a competition. The terms for defining the work of art and the conditions placed upon it after the industrial revolution have been continually fought over since the mid-nineteenth century. The civility of this discourse is most often courteous, but it does get feral on occasion. Think of Michael Fried’s youthful and regrettable jape—“faggot sensibility”—expressed in private correspondence to then Artforum editor Philip Leider. Perhaps aimed at John Cage and tempered by the term “theatricality,” it was dug up fifty years after the initial publication of Fried’s “Art and Objecthood” essay by Christa Noel Robbins to deliver the knockout blow to Fried’s insistence on a kind of dead-eyed version of artistic conviction. Now the term carries a valence that might be more readily recorded as a cancellable offense. Nothing serious.

Needless to say, the competition for the terms that most eloquently articulate what modern art is remains ongoing. One solution has been to accept (nearly) all modernisms as valid; this is liberalism gone wild. As of hornets smoked out of their nest, an exhibition of new work by Lucina Lane and Alexandra Peters currently on show at 1301SW, demands further interrogation, not least because oblique references to terrorism and military livery nested in the works carry far more weight nowadays than during the “holiday from history” we have just been abruptly returned from. This is especially the case when a digital glance at documentation of the show might enamour you to the post-minimal impact of the ten objects on display. Five individual works by each artist face off across the former factory floor, inverted: in the Front Gallery Lane has three smaller untitled paintings from a series that employs roughly hewn tree branches as frames—credited as found elm—all dated 2021. In the Rear Gallery Peters has three paintings from a 2025 series installed in a way that balances, or cancels-out, the two larger works each artist is showing in the alternate gallery. It’s pistols at dawn; all that is missing here is an Ennio Morricone soundtrack piped into the galleries.

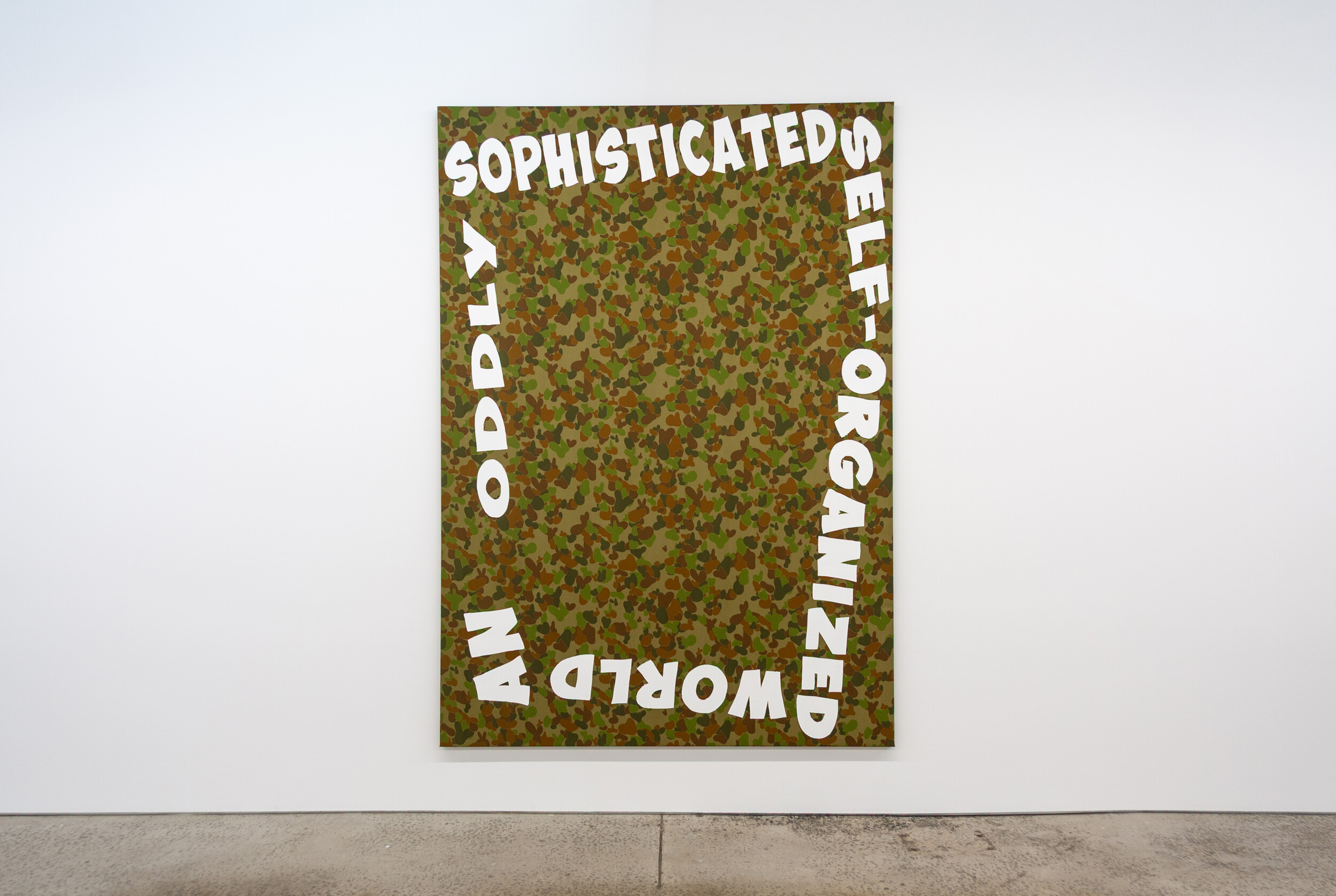

Lucina Lane, Untitled, ((An oddly sophisticated self-organized world) DPCU version), 2025, acrylic on Cordura, 238 x 168 cm. Courtesy of the artist and 1301SW

How productive the narcissism of small differences might be is the central tenet of the show: the hornets are smoked, however, for now the stingers becalmed, stoned. Curated by director Jack Willet, 1301SW is a relatively new commercial gallery usually carrying work by represented artists like the Brisbane-based Michael Zavros or the Canadian-American Jessica Stockholder. A trans-Pacific model links it to separate but related dealer-galleries in L.A. and Auckland, as well as another 1301SW gallery located in Sydney. In South Melbourne, the gallery presents a slightly more experimental project. To enter the logic of the show I recommend starting with the two text-heavy works opposed in the Rear Gallery. The largest work by Lane, Untitled, ((An oddly sophisticated self-organised world) DPCU version), hangs across from a set of three works by Peters, from a series of acrylic, pigment, and water-based ink paintings screen-printed (and pasted?) onto leatherette. Surrogate Activities (nos. 3, 4, and 2) have their title stencilled six times in a circular logo mimicking a vortex, whereas Lane’s haphazard text traces the edges of the canvas. This echoes a previous commission for the ACCA exhibition Like a Wheel That Turns (2022), where the text was a part of Lane’s mural-sized wall painting that responded to the title of the show, with a quote by the South African artist Marlene Dumas, and another lifted from the pages of Spike Magazine. At 1301SW, both of the works with text recall to my mind the work of Liam Osborne, who was a central part of the small scene of artists working in Melbourne over the past decade, and who eschewed commercial aspirations, instead obsessively mining contemporary culture as an archive of post-industrial detritus. The echoes offer a kind of reliquary to the mood, which I had noted at the time was a return of recession art, in turn echoing Peter Cripps. Now placed in a factory setting for commercial art this is what gives me the idea of small differences: networked painting, worlding.

Alexandra Peters, Surrogate Activities IV, 2025, Acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, 135 x 135 cm. Courtesy of the artist and 1301SW

Here is how George Egerton-Warburton described Osborne in his 2022 scene report published in Spike: **** **** ** **** ****** * *** *****. Another line from this piece provided the text for Lane’s untitled text work. Today the words “an oddly sophisticated self-organised world,” describing sub-cultural Melbourne back to itself, are painted on DPCU Cordura fabric. Now phased out of the Australian Defence Force uniform, Disruptive Pattern Camouflage is also known as “hearts and bunnies,” presumably because of the comic shapes of the four different coloured swatches printed onto a lighter ground that is based on the jungle green of the army’s initially monochromatic uniform. Interestingly, military camouflage intersected with art at the height of European avant-gardism, perhaps giving the military metaphor some concrete meaning. British artist Norman Wilkinson’s “Dazzle Section” was set up at the Royal Academy in 1917 so as to protect merchant ships from being torpedoed by the Germans in the Atlantic. The productive binary camouflage/dazzle here is important, however: our optical attraction to something that repels our gaze might just be the fundamental definition of the scopic regime. The military-industrial complex also encompasses art, another definition for total war, in fact.

In combination with Egerton-Warburton’s writing, which at the time appeared to be participating in attempts to reverse-provincialise the centres for art (specifically New York, where he now lives and works), Lane’s work reflects a sentiment seemingly shared by the square panels opposed to it. “Surrogate Activities,” I am told by a user named “froasty” who is posting on the topic “Does computing make the world better?” at the ycombinator Hacker News site, refers to an idea by Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber and domestic terrorist who—despite his death in 2023—continues to inspire what might be called a cottage-industry in militant and doomer-adjacent contemporary art communities. His domestic terror campaign and manifesto Industrial Society and Its Future was originally published as a negotiating tactic in the Washington Post (now owned by Jeff Bezos) on 19 September 1995. It can also be found today as a neatly designed print edition, available in the gift shops attached to contemporary art institutions (I remember seeing it on display at the New Museum, for example).

For Kaczynski, who had conducted his primitivist campaign alone but using the name “Freedom Club” from his remote cabin near Lincoln, Montana, surrogate activities are “directed toward an artificial goal that people set up for themselves merely in order to have some goal to work toward, or let us say, merely for the sake of the ‘fulfillment’ that they get from pursuing the goal.” His example is Hirohito (1901–1989), who pursued and distinguished himself in marine biology after surrendering to Allied occupation after 1945, where formerly he was the Emperor of Imperial Japan. Napoleon III (1808–1873), who designed heat-efficient stoves while exiled in Kent after the French Army was defeated at the Battle of Sedan in 1870, could be said to have pursued a surrogate activity. Perhaps—at least for Peters, who has also shown at ACCA recently, as well as in group shows like Mildura Atrocity Exhibition at NAP Contemporary—the practice of art today is the very definition of an artificial goal, and so the Unabomber reticently offers us a definition of contemporary artistic subjectivity. Here Peters agrees with froasty: “If you’re making useless things, you have a surrogate activity.”

Lucina Lane, Still more to say, 2021, Neoprene rubber, galvanised steel fixings, found elm wood, 225 x 190 x 20 cm. Courtesy of the artist and 1301SW

Egerton-Warburton’s text appears to have been taken down by Spike, the online art platform based in Vienna and Berlin. In his discussion of a very small set of artists’ practices shown in the minor spaces for art in Melbourne and graduating to the minor spaces for art in Australia (ACCA) over the previous decade, one assumption is art’s purposive purposelessness. The thrust of the activities is obvious: the work is strongest when it is small and unambitious. Lane’s elm-wood-framed pictures, iterated throughout the show, seem to eulogise a period that has now passed. Like lifting a rock in a construction zone, all these dank forms of life scatter when exposed to the sunlight for too long, slipping through the cracks, and perhaps gathering elsewhere while new forms are built. The cadmium yellow moss on one section of an elm-branch frame matches the similar yellow of the synthetic fabric that fills the internal void. It is a potent metaphor that, along with the persistent theme of trash or detritus that similarly defines the era of Joint Hassles and Punk Café as locations for this art in Melbourne, might suggest the transmissions or migrations of the same tendency despite the relocation of the work to new contexts.

When the artist-run spaces have become overly politicised and every show feels like a vaguely-defined “action”—against power, against injustice, for Palestine, for (artistic) freedom—or, alternatively, when the major art institutions become so saccharine and smug in their cannibalisation of the entire art world around them (artists either exhibit at the NGV, or work there as installers), it remains refreshing to still be able to enter a commercial gallery showing work like this. As the third arm of the industry, they exist to accommodate the Kaczynskian approach to art as a surrogate activity, a pursuit that is essentially alienating and vocational, professional in the sense that everything is now agreed to be an artificial goal (especially art). Of course, commercial galleries can also become flaccid and self-serving (witness the other month’s art fair/expo and in particular the unconscious symbolism of the blow-up VIP lounge). Artwork here also has a utility, as unashamed commodity. Yet in their carefully put-together and permanently paranoid posturing as both “available” and “exclusive,” commercial operations such as 1301SW can offer up a salve to the artwork instrumentalised by meaning, and instead allow us to see art that is only instrumentalised by capital. This is the natural home of the avant-garde: petit-bourgeois and unattached, purposely purposeless.

Alexandra Peters, Fenestration (Auto-Extrication), 2024, acrylic and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, four parts, 250 x 480 cm (overall). Courtesy of the artist and 1301SW

There is one problem, however. “Only through hardship, sacrifice and militant action can freedom be won,” says Nelson Mandela. (At least Bibi Netanyahu had the conviction to skip the anti-apartheid leader’s funeral in 2013). Mandela led South Africa in the same moment as the Freedom Club’s domestic bombing campaign in the US. Peters’s screen-printed abstract canvases, especially Fenestration (Auto-Extrication) (2024), could be considered a type of camouflage in the ab-ex vernacular of the twentieth century. Hidden deep within the forest of contemporary art is a different type of conviction, a belief in the authenticity of radical gestures. In an essay recently submitted to my class on Post-War Art, Hoang Tran cited a typically incisive remark by Andy Warhol. It replayed in my mind as I looked at both Peters and Lane’s work on display in the gallery: “It must be hard to be a model, because you want to be like the photograph of you, and you can’t ever look that way. And so you start to copy the photograph.” The radicality of the print that hides the expressive gesture mimicking the print—a strategy that seems to be at play in Peters’s use of the screen-print medium—expands the notion of the model outward from its embodied image of Warhol superstars and cinematic tragedies and into the objecthood that is their destiny. The real is found in the copy, yet Peters’s conviction here is a challenge to Lane’s ironic distancing effects. Despite the pairing of two artists with formal similarities in their work, their intentions are revealed to drastically diverge.

Let me expand on this in a final example: Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson’s film Elms (2015) is a sub three-minute short for promoting the release of Maddin’s My Winnipeg (2007) by the Criterion Collection. “Elms are everywhere in Winnipeg,” Maddin claims online. “When a Winnipegger beholds a beautiful elm, he or she uncomprehendingly beholds almost the entire history of the city.” The reticulated voice-over in the short film notes how, “in winter, the towering elm sheds its leafy vestments and takes on sinister and portentous aspects.” This is how I understand Lane’s use of elm—as crudely-wrought stretcher bars for found and soiled synthetic fabrics holed away between the branches. What is sinister, ultimately, is the dead wood that comes from diseased and atrophied European stock that continues to thrive in the former colony. There is a hidden crowbar behind Peters’s Double Happiness (2025), which holds it to the wall-mount. It’s timber versus steel. Rock, paper, scissors.

Giles Fielke is an editor of Memo Review.