Gabi Briggs, ARKAN & IRBELA, still from moving image, 2024. Courtesy West Space.

Arkan and Irbela

Susie Anderson

I know these hands is my first thought as I begin watching Arkan & Irbela, the debut filmic work by Anaiwan Gedyura artist Gabi Briggs currently showing at West Space. The video shows a group of women sitting around a dimly lit table, dressed in plush bathrobes, carefully sorting through blades of lomandra. It’s adorned with finely woven mats, vessels, and candles, casting a soft glow around the room. From a bird’s-eye view, I watch as bony, brown, and bejewelled hands reach for their next blade. At the centre of the table sits the artist, using her long nails to split the grasses into smaller pieces for weaving. The nail colour of each woman matches her robe, and they sit close to others wearing the same colour. One woman suddenly gets a nasty jab as she bundles up several grasses. I wince. It’s a familiar sting—like a paper cut, but worse. She shakes her hand gingerly and keeps going.

This subtle humour threads through the film, balancing the strength and pride that anchors the artist’s central messages about family, resilience, and culture. In this scene, there’s a focus to their work, an almost serious attentiveness to the task at hand. There are certain obvious artistic references in the mise-en-scène—da Vinci’s The Last Supper immediately comes to mind (or is that van Bijlert’s The Feast of the Gods?). Briggs joins a lineage of First Nations video artists who use the medium to retrace steps and reclaim Country through immediate or ancestral family stories. Though varying in their tone, references like Richard Bell’s recent No Tin Shack (2022), Amala Groom’s The Union (2019) and r e a ’s PolesApart (2009) surface, as well as the more closely linked Julie Gough’s film Observance (2012). There’s also something of The Sopranos’ dark humour in the scene, reminding me of the table in the back room of one of Tony Soprano’s venues, and the sense of power emanating from each cluster of women, and what they may be capable of. An occasional word or remark is exchanged, and if this table is anything like the weaving circles I’ve sat around, I bet topics range from serious to funny to sad and back again.

But we don’t hear what they’re saying. In the film’s background are woman’s voices, a partially audible crackling fuzz. This is a poetic execution of the inter-generational dialogue referred to in the exhibition statement, evoking conversations Briggs’s nan, Patsy Cohen, undertook as part of the research for Ingelba and the Five Black Matriarchs (1990). This important book was a project for Patsy Cohen, who commenced a series of walks on Anaiwan Country in Northern New South Wales in the late 1980s with family and community members, to recover and surface family knowledge of Country. The book holds stories stretching back to the 1800s and was vital in Briggs’s development of Arkan & Irbela. A well-worn copy of the book sits at the gallery entrance, but it is helpfully also available online. Voices ebb and flow over the whispers and rustles of the grass blades, creating a compelling soundtrack. It simultaneously feels as though you are being told something crucial, or trying to recall a memory you can’t quite remember—yet the volume won’t go any higher.

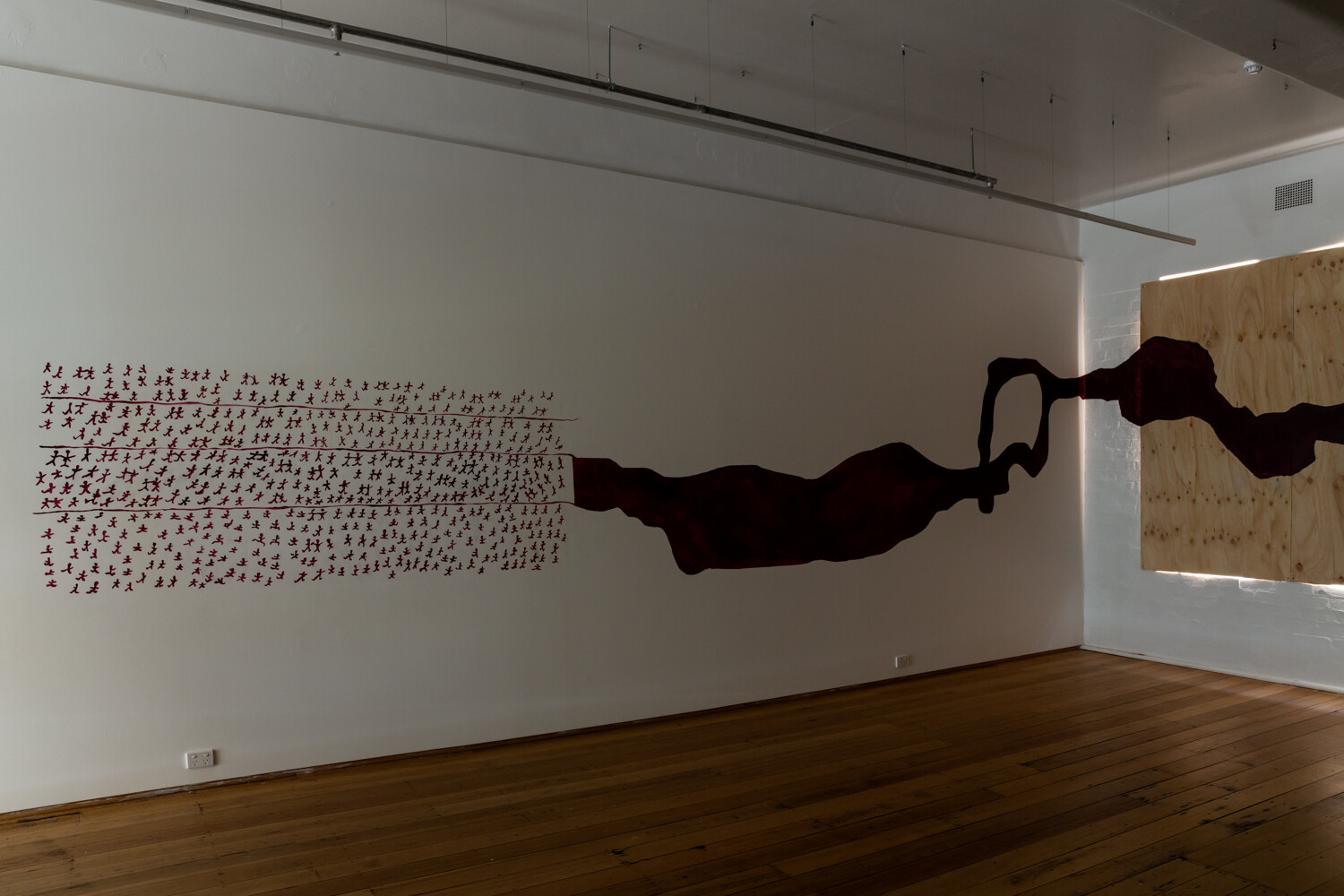

Gabi Briggs, ARKAN & IRBELA, installation view, 2024. Photography by Janelle Low.

These sophisticated symbolic choices continue throughout the exhibition. The short film follows the women and their family members from the domestic scene to a gathering on Country, walking through the bush, and by the river. The river is another key feature of the physical space, recreated in a deep, blood-red mural, which flows forth from an illustration at the gallery entrance. This mural is drawn directly from Black Matriarchs, indicating the generations and descendants of the five Black Matriarchs from Anaiwan Country. I’m obsessed with the colour. It is deep, bold, and inky in some places, transparent in others. Despite the tonal variation, I nearly missed the other illustrations from the book, painted subtly into the river around the gallery walls. They are so understated that they’re easy to miss. One section is lit to invite a deeper look, revealing further sketches of Patsy’s Ingelba encoded within the river.

By then, I was already downstream in my many other readings of this blood-red river: it’s simultaneously connection between generations and family; the colour of red ochre, the earth; what was spilled during invasion, displacement, violence against our people; and the insidious classification systems that gave government permission to separate families. In Ingelba and the Five Black Matriarchs, Patsy Cohen details how her early life was marked by the latter policies. Yet here, the blood connects generations, rivering its way across Country: “retta ya-na/the river still flows.”

Gabi Briggs, ARKAN & IRBELA, installation view, 2024. Photography by Janelle Low.

West Space’s four large windows are covered by plywood sheets to darken the room for the film’s projection. This material recalls the shacks and structures from Patsy Cohen’s walk on Country at Ingelba. Light sneaks through the uneven edges of the windows, creating a beautiful ambience in the room, and offering up another symbol between the space and the film: what (or who) is on the other side? The exhibition is full of these cyclical metaphors, and actual poetry is woven into the film: “Our hands dance with reeds to make netbags.”

The exhibition blurb states there is a “coded knowledge and stories from family history” throughout the show. Certain scenes in the film refer directly to information or photographs from Black Matriarchs, such as the plywood for the shacks or the robe colours symbolising family belonging. I appreciate that only some of these codes are available to me; but they also evoke other key scenes from Australian art, such as the scene featuring family members seated on the granite outcrop holding a coolamon in their lap, reminding me—although it’s different Country—of William Barak’s drawings of women at corroboree playing possum skin drums.

Gabi Briggs, ARKAN & IRBELA, installation view, 2024. Photography by Janelle Low.

On each viewing of the film, I pick up something new. Although it’s short, it becomes almost like a meditation as my attention rests each time on something different, so I’m not just entering a different place, but also a different time. This feels similar to the way the five Black matriarchs are described in the book: they “straddle two worlds.” As Margaret Somerville, co-author of the book states: “They were born to parents who would have known life before white settlers arrived, but by the time the five matriarchs’ children were born, almost every aspect of their lives had changed.” While I read the cues and understand parts of the coded messages, I remember the hands of my aunts or recall weaving circles I’ve sat around. Ultimately this project foregrounds Anaiwan knowledge, skinship systems; it is about and for family.

Even as I tread lightly through the space, there is a form of eavesdropping going on, from non-Aboriginal audiences who view projects like this. Arkan & Irbela is playing with these layers of access: that’s why the muffled voices are amplified. Those who are implicated in the very reasons First Nations families must work to recover culture across generations should, perhaps, have limited access to what the women are saying. Settlers imposed their own lineages on top of ours, bringing with this erasure an unwillingness to hear what other stories Country held or what Aboriginal people had to say about their experiences. The soundscape of the film also prompts the listener to wonder whether they should have the privilege to listen in now. What layers of meaning are available to whom becomes a key question of the work. As the family members stand in their skinship clusters in the final act of the film, the artist staunchly reminds all of us this will always be an Anaiwan Gedyura artwork that both enlivens and memorialises culture for community.

During my later reading of Ingelba and the Five Black Matriarchs I was moved by the section of the book called “The Ingelba Event,” involving a walk on Country with community members. This particular moment was instructive for Briggs in developing the exhibition, in terms of its content and many of the photos that are replicated in the film’s scenes and illustrations in the mural. Here Patsy’s conversation with Ethel de Silva, a senior woman in the community, is hauntingly relatable, with both lamenting that they should have “done this years ago … when Uncle or Aunty was still alive.”

Gabi Briggs, ARKAN & IRBELA, installation view, 2024. Photography by Janelle Low.

This is an important, human reminder that even those who are now our Elders have experienced times where it felt like important knowledge was fading from view. It brings a certain melancholy, as I feel aligned with a generation that seemed lucky to have connections to their Elders—some with knowledge of traditions and practices stretching back to the days of first contact. Yet this is the reality of being colonised people: it feels as though something is lost every day.

Patsy’s foresight in preserving what her Elders remembered, to recover what was taken from her, shows her profound dedication and care for future generations. Gabi Briggs continues this lineage, taking a crucial next step in Anaiwan cultural revitalisation within her arts practice. The cycle continues as ancestral knowledge, family voices, symbols of time, place, people, and Country now flow within the film and exhibition Arkan & Irbela.

Susie Anderson is a Wergaia & Wemba Wemba writer. Her poetry book ‘the body country’ was shortlisted for a NSW and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award.