Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

Archie Moore, kith and kin

Verónica Tello

On a balmy Sydney evening, I board the EK413 9:10 pm flight to Venice (with a stopover in Dubai). After walking past the friendly Emirates hosts, impeccably dressed in beige suits and lush, red velvet hats, I eventually find my seat, 64J. Out of the seven hundred passengers on board this Covid-19 cesspit, the art gods have determined that I will sit next to the renowned curator Djon Mundine—a long-term confidante of Archie Moore and advisor for kith and kin at the Australian pavilion. I only know Mundine by reputation. But he is unmissable in 64H, where he sits with his crown of epic dreadlocks.

Before taking my seat, I spot my colleague José Da Silva, Director of UNSW Galleries, a few rows behind me. He walks over, asks Mundine and me if we know each other, and then enthusiastically introduces us. As I secure my seat belt, Mundine mumbles, “I hear you’re a critic. I better watch myself: this will be deemed either a very good or very bad flight.”

For those who know Mundine, you’ll rightly assume that as soon as the plane lifted its little wheels off the ground, we didn’t just begin a sixteen-hour journey to Dubai but a marathon conversation. Incredibly well-read and unsparingly generous, Mundine was keen to discuss many topics, including his essay in the kith and kin catalogue. He tells me how he opens the text with an anecdote about an enigmatic and rare night parrot that has never been seen, was once thought extinct, and leaves only the faintest traces of its existence behind. Then he reflects on how Moore’s often autobiographical work, such as his 2018 solo show Archie Moore 1970–2018 at Griffith University Art Museum, allows the artist to recuperate histories under threat. And then how, for the Venice Biennale, Moore uses himself once more as an origin point for generating a vast tree of life.

Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

As we flew over the Indian Ocean, I veered our conversation toward the history of international exhibitions of Aboriginal art. I asked Mundine if he’d been present at the 1983 exhibition From Another Continent: Australia, the Dream and the Real, curated by his friend and collaborator Leon Paroissien at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Or if he remembered much about a panel he was on with Gary Foley, Juan Dávila, and the French-Chilean essayist Nelly Richard about Aboriginal and Third World solidarity at the 1986 Biennale of Sydney, curated by Nick Waterlow. Mundine hadn’t been in Paris for From Another Continent, but he had heard that the esteemed French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss had attended and said something like, “Look at the Aborigines, look at their fascinating gestures,” reducing them to objects to be analysed. At the 1986 Biennale of Sydney, he said the panel, particularly Foley, confronted the persistence of the ethnographic gaze toward Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and artists from the Third World in Australia.

As we compared notes on the history of international exhibitions, Mundine also related how, in Australia, Aboriginal people are refugees in their own country. He told me that his father needed to carry a passport for much of his life; the missions were like a prison on the island continent for Aboriginals, while most of the settlers from the old world roamed free.

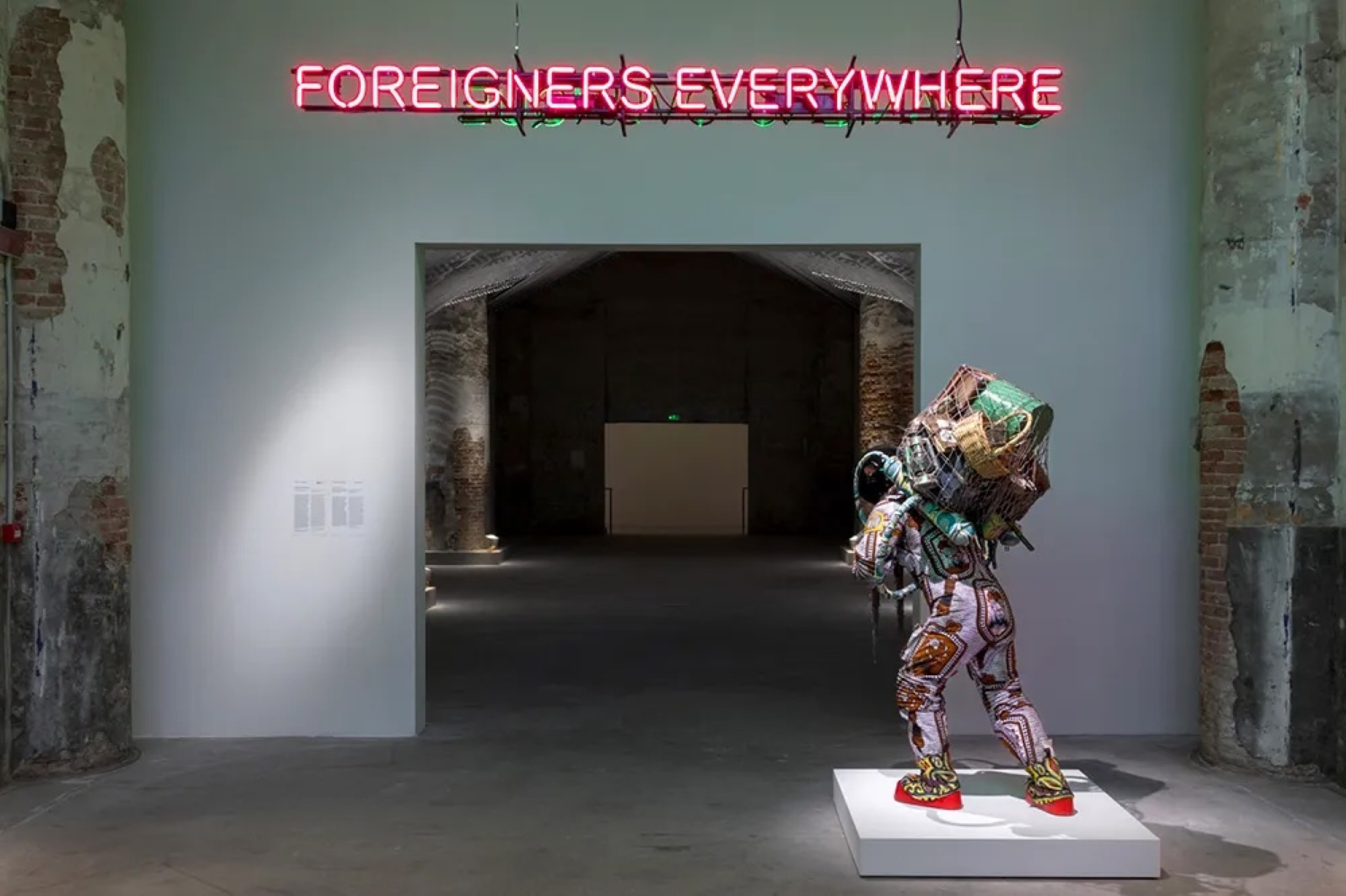

Installation view of Foreigners Everywhere (2004–) by Claire Fontaine and Refugee Astronaut VIII (2024) by Yinka Shonibare at the 2024 Venice Biennale. Photography by Marco Zorzanello. Image courtesy of the artist and La Biennale di Venezia.

Foreigners Everywhere is the title of this year’s Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP). It’s worth dwelling on Pedrosa’s theme. Because even though it does not frame the national pavilions such as kith and kin, public reactions to the theme revealed how some people, other than Pedrosa or Mundine, relate to the label “foreigner.” When it was announced a few months ago, it provoked strong reactions. Some enacted moralistic takedowns of the title, even though the Biennale had not yet opened, arguing something along the lines of “it’s unethical to brand indigenous artists in the Biennale as ‘foreigners.’” Pedrosa’s title is drawn from a work by Italian-British collective Claire Fontaine: a neon sign that shows the phrase “foreigners everywhere” translated into dozens of languages. The phrase sounds like the sort of thing right-wing politicians say to fuel xenophobic border politics and protect the purity of the nation-state. Pedrosa’s intent is to co-opt the phrase and power of foreignness—of being labelled “not of this place”—and to, in turn, invent joyous, radical, potent, dangerous, and unfamiliar ways of being. While kith and kin is not part of Pedrosa’s curated exhibition, both shows approach the category of the foreigner and its binary opposite, the citizen, with caution. Indeed, Moore and the curator of the Australian pavilion, Ellie Buttrose, made the point in communications for kith and kin that the artist was “presenting” work in the Australian pavilion and not “representing” the nation-state.

Given how much media attention Moore’s work has received in the last three weeks, it feels like overkill to describe kith and kin again. But what is a review without visual analysis?

Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

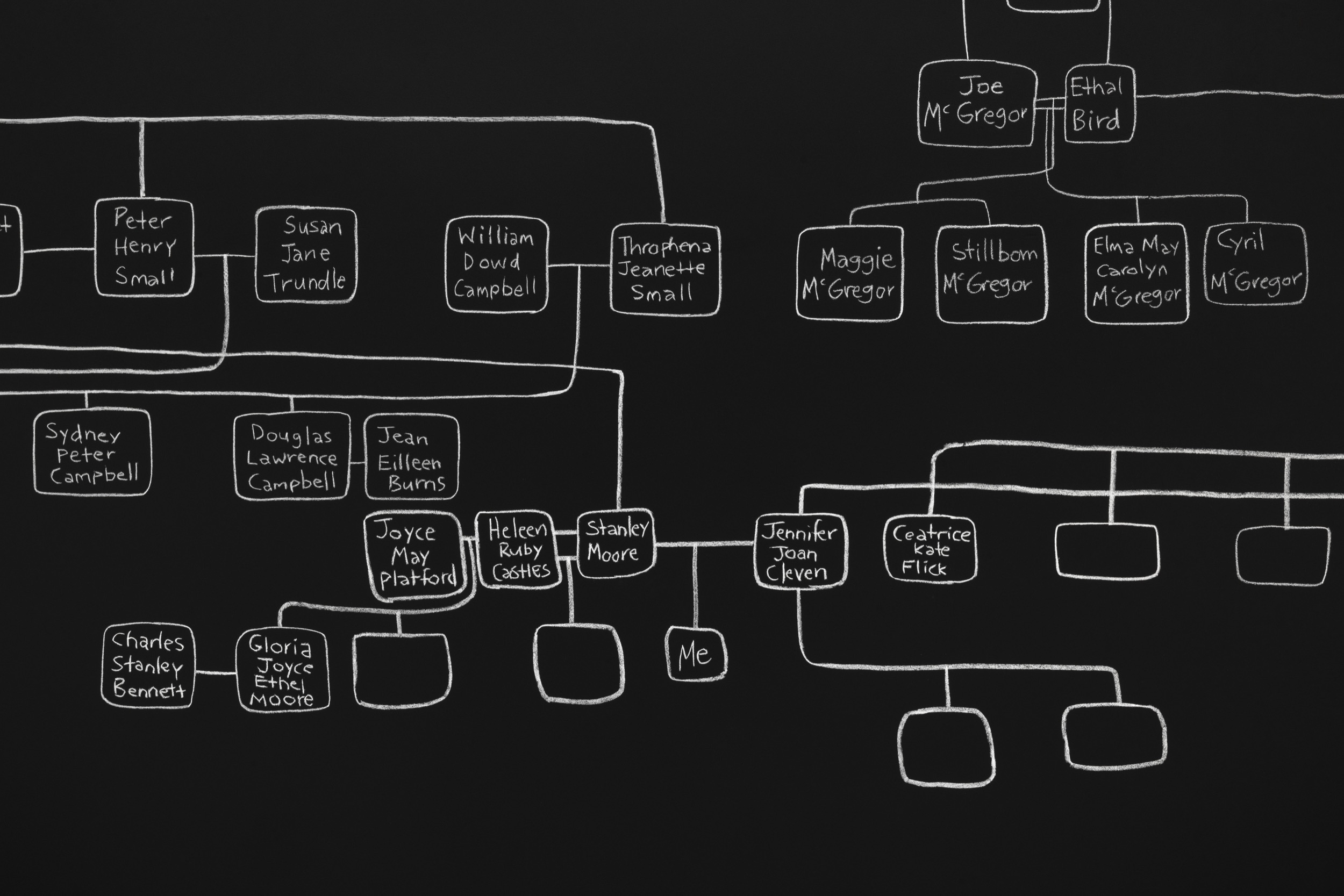

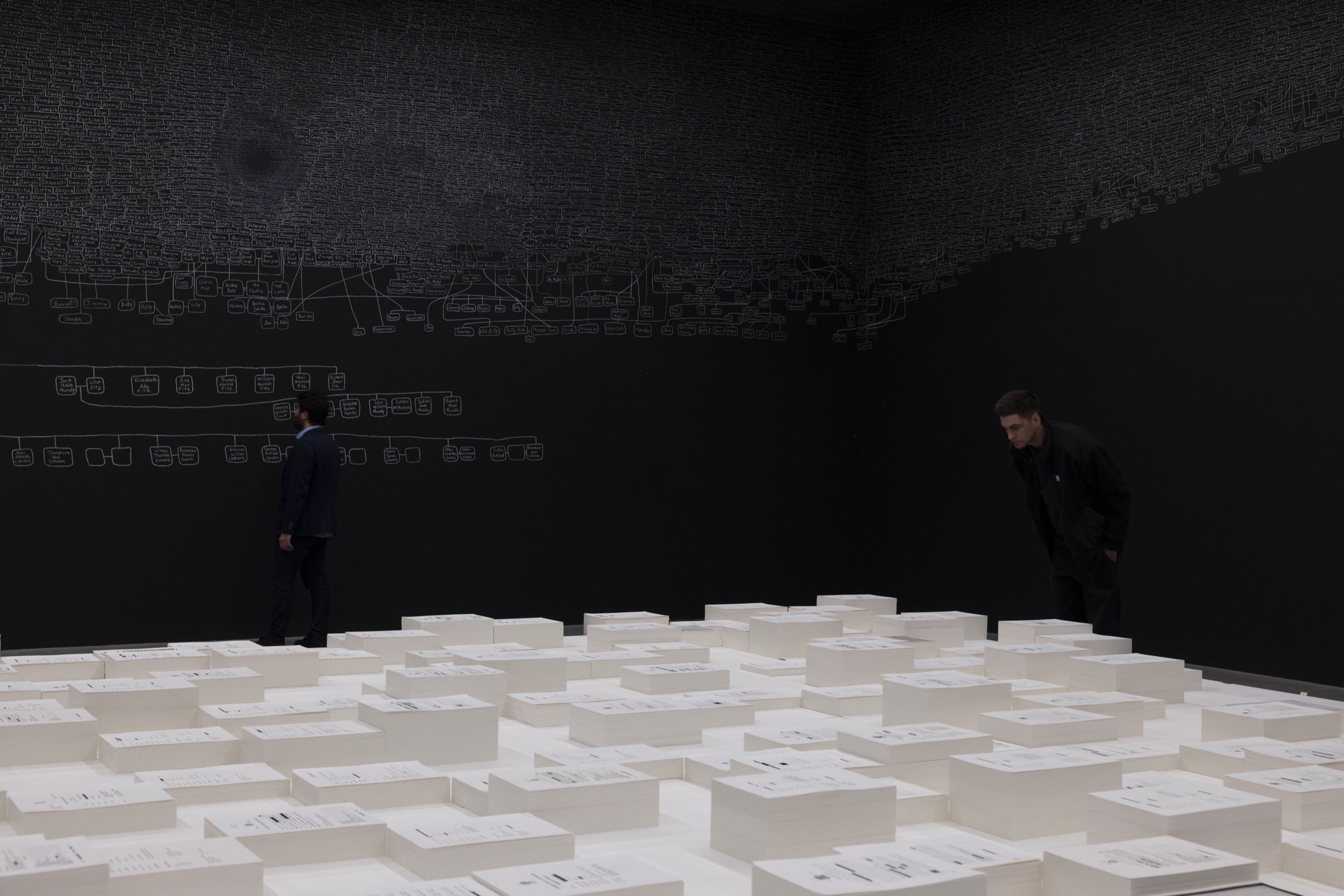

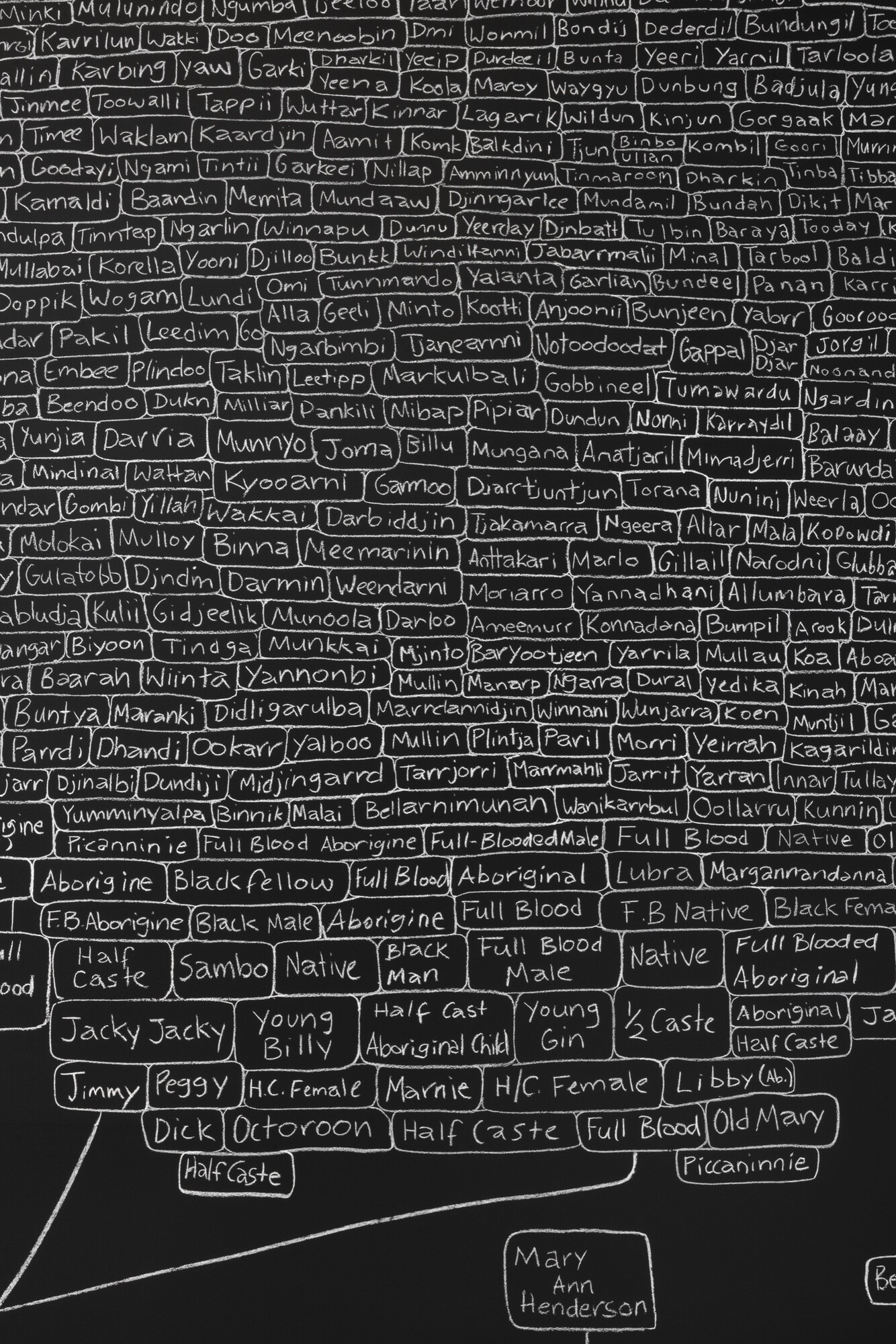

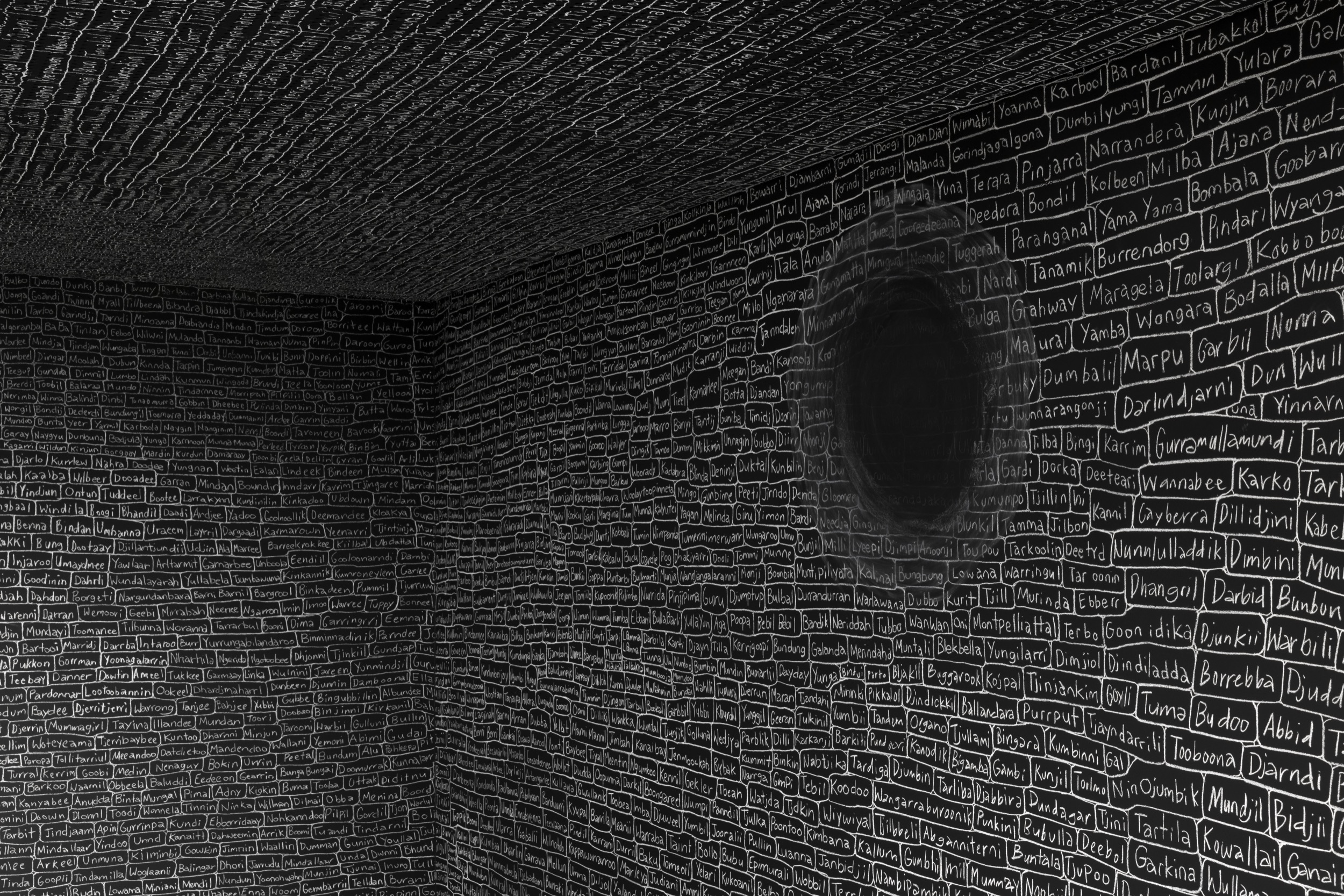

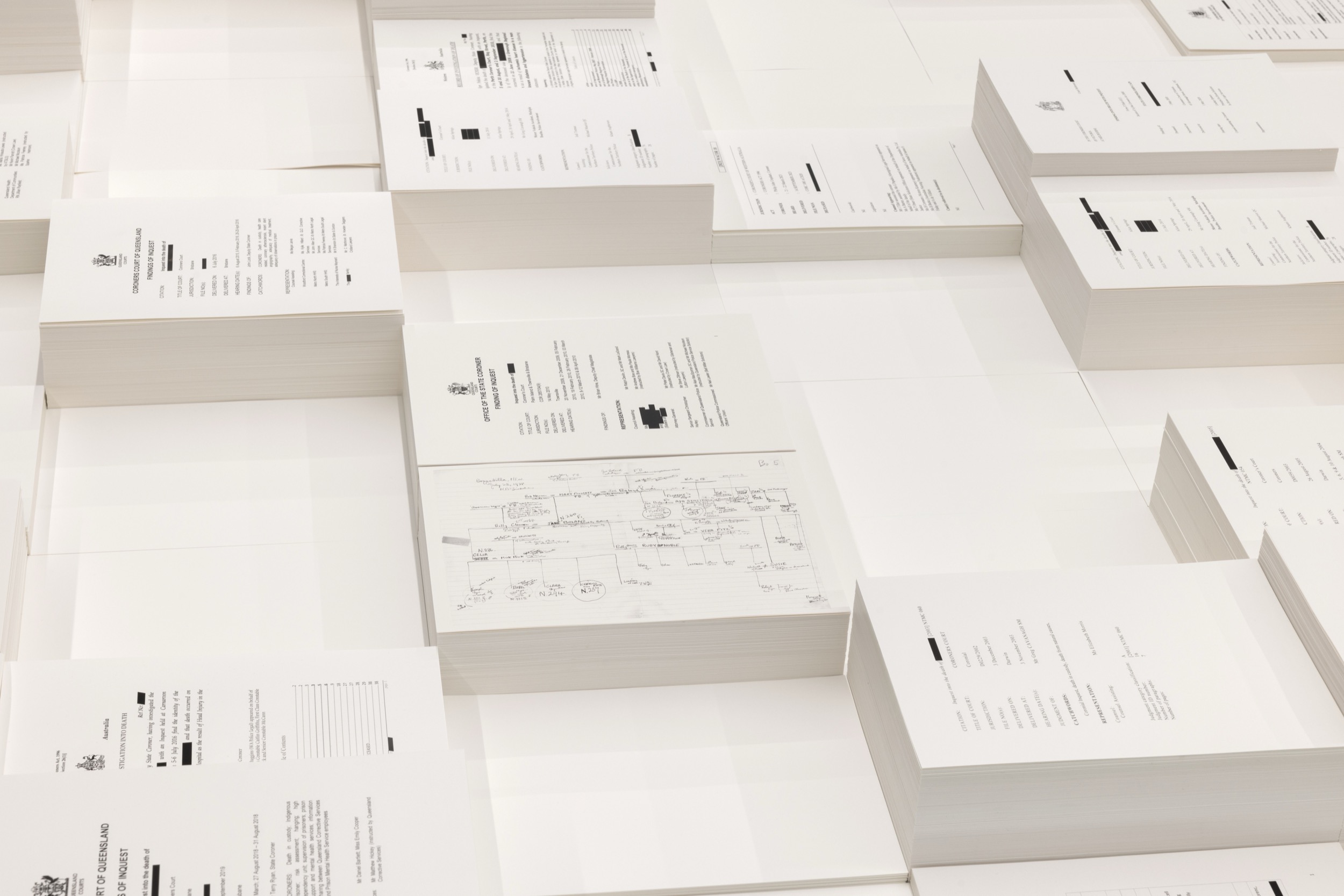

As almost every report on kith and kin notes, the work demands an attentive viewer. The pavilion is dimly lit. Its walls are coated in blackboard paint, while its centre holds a large black and white plinth bordered by a shallow pool of water. On the plinth sit more than five hundred stacks of varying heights comprising hundreds and hundreds of redacted documents. The documents mainly represent coroners’ reports of Indigenous deaths in custody—generated since the 1991 Royal Commission on Indigenous Deaths in Custody. But, some of the stacks also hold documents from Moore’s family archive, revealing how the nation-state has systemically surveilled them and restricted their movement and freedom since colonisation. Initially, the white glow of the documents absorbed my attention, but I was also vaguely aware of the white chalk drawing on the walls. As my eyes adjusted to the light, the scale and intricacy of the wall drawing emerged. The drawing is, in fact, a map or family tree of blood and chosen kin, which stretches all around the pavilion. As the wall text in the pavilion notes, the tree spans at least sixty-five thousand years, affirming Indigenous sovereignty. The family tree starts just below my eye height and crawls up toward and across the ceiling. There are thousands of names. Names registered by the nation-state, names inflicted on people, names as tools for surveillance, names that become stuck and unstuck, names branded by racial slurs, Indigenous names, names lost and reclaimed, and speculative names. At dinner later that night, a friend told me they thought they had seen “Eminem” on the map. I’m sceptical.

Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

On the opening day, people gathered around a particular section of the pavilion. I walked over to join them. Here, a humble “Me” is etched in chalk onto the wall, signifying the artist himself. Moore’s mother, “Jennifer Joan Cleven”, of Kamilaroi and Bigambul descent, sits above, branching out to Moore’s right. The artist’s paternal line, of British and Scottish convict heritage, branches out to the left via his dad “Stanley Moore.” I hear Buttrose tell someone that the circular, sometimes smudged, voids in the family tree reference the erasures and historical breaks born out of genocide, disease, and the destruction of records.

Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

As I walk around, some people willingly put their shoes—Hokas, Salomons, Docs, Balenciagas—into the pool surrounding the central plinth, checking if it contains actual water. It does. Others are accidentally stepping into the pool, presumably attempting to read the covers of the coroner reports, an arm’s length away on top of the plinth. The work holds the viewer at a distance, affirming Indigenous peoples’ right to privacy and opacity.

A heedful viewer would see the chalk drawing of celestial names and their image reflected in the pool. As Moore has repeatedly said, his family tree stretches back so far that it connects all humanity, including you, me, and them. However, for Moore, the idea of “kith and kin” is not limited to human bonds or friends and family. It taps into a forgotten fourteenth-century-old English understanding of “kith,” which grounds this concept in human connections to the land, resonating with Indigenous kinship systems.

Tahmina Maskinyar viewing Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

A work of undeniable conceptual and technical accomplishment, kith and kin is nonetheless a quiet and earnest work. It is an anti-spectacle, which places it in stark contrast to some of the more popular—or most queued for—national pavilions during the Vernissage week (i.e., before the Golden Lion was announced). Germany and Egypt, which exhibited flashy, resource-heavy, expensive-looking artworks (including immersive trompe l’oeil installations, complex kinetic sculptures, and epic video art), demanded one to two-hour queues. While waiting outside the Egyptian pavilion, I heard someone say they couldn’t see the family tree all that well as the Australian pavilion was too dark. Another person reported that the Australian pavilion wasn’t exhibiting “Aboriginal art.” During the Vernissage, people are in a rush, chasing the hype and not always paying attention to the details.

Queue for German Pavilion. Photo: Verónica Tello

The hubbub of the Vernissage reminds me of the sheer strangeness of the Biennale format: a collection of nation-states (each represented by a pavilion) vying for crowds, media attention, cultural capital, soft power, and the coveted award for best pavilion—the Golden Lion. Yet, as protestors, organised by the Art Not Genocide activist group, arrived at the Biennale to call for a ceasefire in Gaza, I was reminded that, for all its spectacle, this event can still offer a platform to critique and contest state violence.

Protests organised by Art Not Genocide outside the US pavilion (pictured) and the Israeli pavilion (not pictured). Photographer unknown.

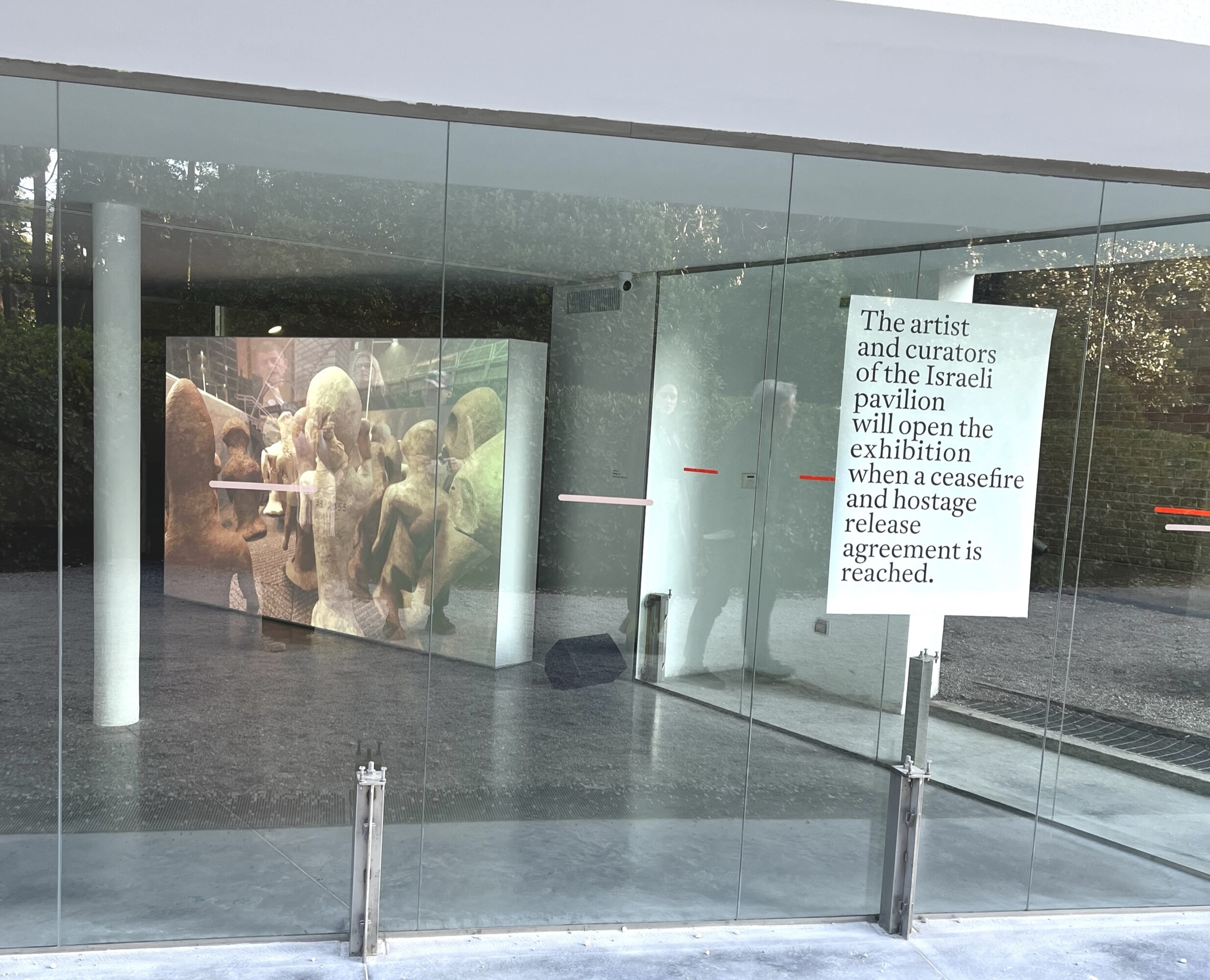

Some pavilions tried—or gave the impression of trying—to challenge the nation-state. They delegated their exhibition spaces to precarious states: Russia opened its pavilion to Bolivia, Poland to Ukraine, and the Netherlands to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (by way of Dutch artist Renzo Martens). The Israeli pavilion refused to open its doors without a ceasefire (and the release of hostages), a decision made by exhibiting artist Ruth Patir and curators Tamar Margalit and Mira Lapidot.

Poster outside the Israeli pavilion declaring conditions upon which it will open. Photo: Verónica Tello

Are these varying gestures of border-crossing solidarity simply compensating for the fact that, outside the bubble world of the Venice Biennale, the nation-state remains a robustly colonial project? Within the context of the Australian pavilion, does kith and kin fall into the same genre of pavilion as Israel, Russia, Poland, and the Netherlands? I don’t think so, but it’s worth exploring the stakes of the work to figure out what’s at play.

The stakes of kith and kin are quite literally life and death. kith and kin is the culmination of the extensive research that Moore has undertaken into both his family history and the history of Indigenous deaths in custody in Australia. Moore draws on The Guardian’s “Deaths Inside” online database of coroners’ reports on Indigenous deaths in custody from 2008 to 2021, and combines this with earlier and more recent reports, downloaded directly from state and territory coroner’s websites. If you could read the documents on the plinth, or if you open the reports in “Deaths Inside,” you would find expressed again and again coroners’ frustration at the failure to implement recommendations from the 1991 Royal Commission. As well as an examination of the circumstances of their deaths, most of the reports include information on the deceased’s life beyond their incarceration, including their kin.

Placing the coroner’s reports at the centre of Moore’s family tree not only references experiences of imprisonment on both sides of Moore’s family, but also that the deceased are themselves bound to all of humanity through kin. Lorena Allam, The Guardian’s Indigenous Affairs Editor, emphasised the importance of family, whether blood or chosen, when she spoke at the kith and kin symposium on 18 April, the day after the show’s opening. Allam described how the “Deaths Inside” project had changed how The Guardian reports Indigenous deaths in custody, with reporters now speaking first to family members of the deceased and centring their experiences.

Archie Moore, kith and kin 2024. Curated by Ellie Buttrose. Australia Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Project team: Adrian Collette am, Diego Carpentiero, Gillian Mercer, Mikala Tai, Niwa Mburuja, Tahjee Moar, Tahmina Maskinyar, with the support from the wider Creative Australia team. Photographer: Andrea Rossetti, © the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and The Commercial.

A couple of days after the symposium, on 20 April, kith and kin was awarded the coveted Golden Lion. In Australia and internationally, the news stories have been consistent and abundant. Social media has also gone mad for kith and kin, with what seems like hundreds of posts and stories—even Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, @albomp, joined in, celebrating the “win.” Many Australians and local news outlets have compared the Golden Lion to winning the World Cup or Olympic gold. These sporting metaphors are not interesting or novel. And that is the point. We are familiar with celebrating our sporting heroes. Competition is a staple of Australian culture. But Moore and Buttrose refuse to “represent” Australia.

Screenshot of Anthony Albanese’s Instagram account celebrating the Golden Lion win.

And what of the relational, collective ethos of kith and kin? It rubs against the grain of exceptional individualism that events such as the Venice Biennale traditionally encourage. It asks us to, instead, have a duty to each other. And, to borrow the title of kith and kin’s symposium, it proposes that we do so because this is “art for abolition.” As abolitionist and writer Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, “one need not be a nationalist, nor imagine self-determination to be fixed in modern definitions of states and sovereignty, to conclude that, at the end of the day, freedom is a place. How do we find the place of freedom? More precisely, how do we make such a place over and over again?” Part of the jubilation following the announcement of the Golden Lion came from the wanting to commune and join forces with kith and kin, and negate a world that systemically creates social, political, economic, and cultural losers and winners.

Moore and Buttrose with the Golden Lion at the Biennale’s award ceremony. Getty Images: Felix Horhage

Paradoxically, part of the jubilation was also born out of the reprieve the Golden Lion offered those suffering from cultural cringe, as it showed some that “we”, Australians, can be the winners of international art after all. Others just appreciated Moore and Buttrose’s anti-spectacular, quiet, smart, thoughtful, relational, and emotional approach to exhibition-making.

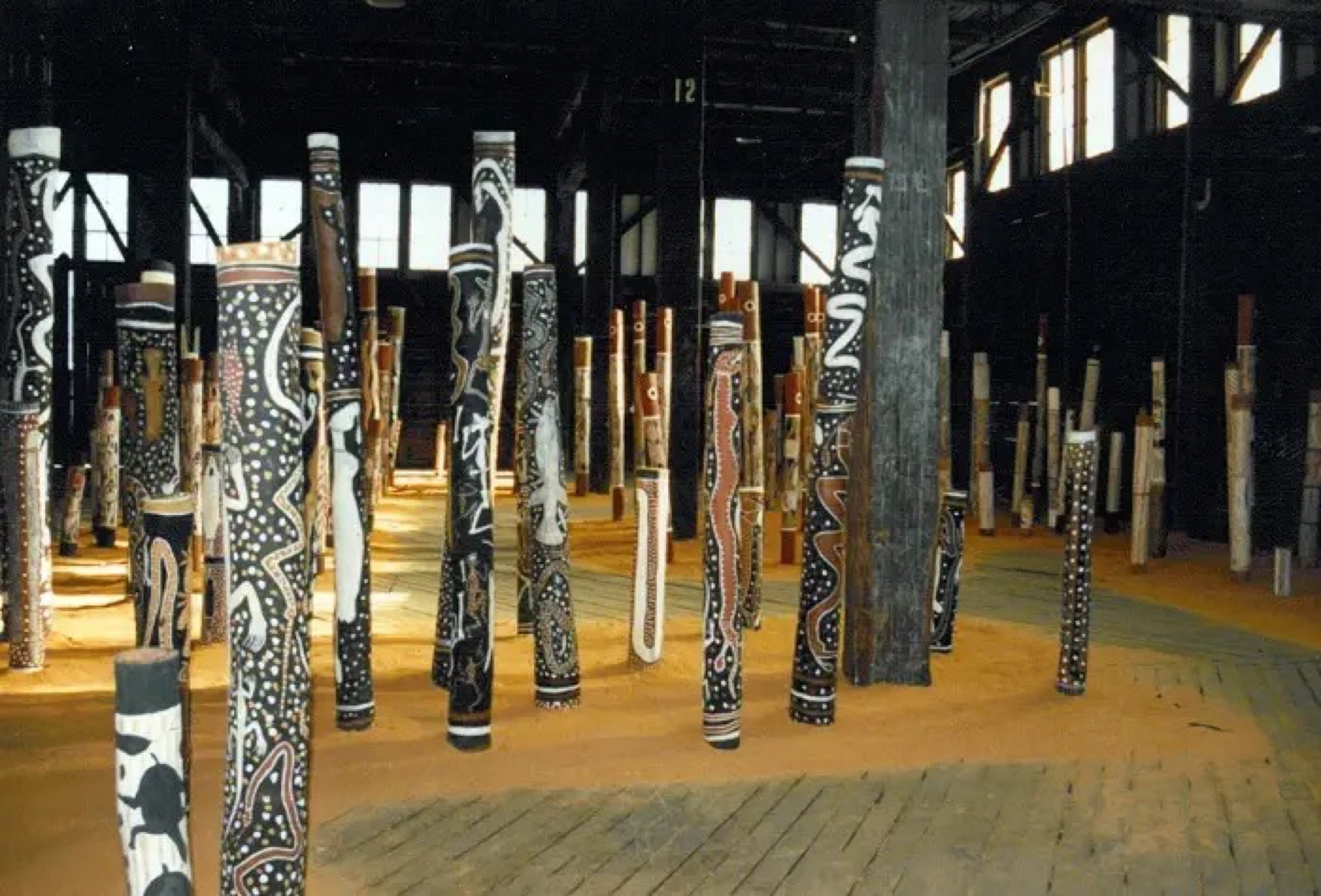

It will be interesting to see the reception of kith and kith when it is shown outside Venice and within the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in 2025/2026 (date TBC). I doubt comparisons between Moore’s sombre, moving, demanding memorial site and the World Cup or Olympic gold will be made there. Instead, I imagine the exhibition will powerfully invoke The Aboriginal Memorial (1987–88), conceived by Mundine in collaboration with Yolngu artists. Moore’s work stands not only in the space of global contemporary art but also within a more local history of Indigenous memorialisation, in which Mundine is a crucial figure.

Djon Mundine and his crown of dreadlocks entering the Venice Biennale. Photo: The Commercial

The Aboriginal Memorial (1987–88) commemorates the tens of thousands of Aboriginal peoples who lost their lives fighting for their land and sovereignty from 1788. Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia and first shown at the 1988 Biennale of Sydney, directed by Nick Waterlow, the Aboriginal Memorial was part of the social and cultural movement that ruptured and refused the euphoric celebrations of the Australian Bicentenary. It used the space of global contemporary art via a biennale to mobilise change on a local level.

The Aboriginal Memorial, 1987–88, 200 hollow log bone coffins, installation view, 7th Biennale of Sydney, Pier 2/3, 1988. Courtesy of the artists and the Biennale of Sydney

Almost forty years after The Aboriginal Memorial, Moore’s work is doing (at least) two things that are especially meaningful within the context of the Venice Biennale and contemporary history and politics in Australia. On the one hand, kith and kin is enacting a forceful and damning critique of the nation-state by framing the history of Indigenous deaths in custody. On the other hand, the work proposes its own sovereign reality—which Moore calls “kith and kin.” This form of relationality is neither the smooth network of global contemporary art (or capital) nor bound to the geographical, political, and bureaucratic limits of the nation-state. Instead, it emerges from Indigenous kinship systems, dispossession, displacement, family connections, friendships, love, death, birth, and shared loss.

In this context, the Golden Lion win poses some interesting challenges to the legacy and future of kith and kin. On the one hand, it could risk the work’s subversiveness—it is an attempt to refold the work back into the Biennale’s logic of global art competition and the nation-state (Albanese claiming Moore as a national hero while obscuring the history of Indigenous deaths in custody for which he, as Prime Minister, is responsible). On the other hand, kith and kin, is structured by its own logic, shaped by Indigenous knowledges, seeking to create the kind of “place of freedom” that Ruth Gilmore talks about. And now it has everyone’s attention.

We can celebrate the Golden Lion win without buying into the nation-state’s co-option. The question is how will kith and kin—and its insistence on the interconnectedness of memory, life, and death—move us when the work is presented in Australia? How do we support it to find the place of freedom again and again?

Finalised just three years after the Bicentenary celebrations, the 1991 Royal Commission asked for each Indigenous death in custody to be investigated and for the findings to be made public with the hope that it would precipitate change. The reports are fragmented across disparate state archives and held in clunky online portals, making it difficult for the public to search and access them. While The Guardian’s “Deaths Inside” makes the reports more easily accessible, the point of kith and kin is to emphasise the distance between the viewer and these documents while simultaneously connecting us to the lives and deaths in these coroners’ reports and the family tree. In Moore’s conception of “kith and kin,” we are mobilised to action (if not, we all lose).

Verónica Tello is a writer based on Gadigal land and a senior lecturer of art history at UNSW Art & Design.