Angela Brennan: Forms of Life

Julia Lomas

In Angela Brennan’s exhibition at the Potter, a wall painting of textual fragments poses the question: “What do you want a poet for? To save the city of course!” Brennan’s engagement with the artefacts of early Greek and Cypriot civilization has been framed as an investigation into how such signs, symbols and forms persist through the ages, contributing, as director Kelly Gelatly’s catalogue essay has it, to “thinking and making in contemporary art”. Brennan has crafted responses to the University of Melbourne’s Classics and Archaeology Collection, and the conventions and mannerisms of ancient pottery and vase painting are here rematerialized with exuberant and poppy splashes of colour, thick brushstrokes and simplified cross hatching, and polka dot and stripe patterns. The premise of the exhibition – to investigate how such forms resist periodisation and inform contemporary sensibilities – seems rather like a foregone conclusion. To me it seems the question is not whether motif and symbol from antiquity inform contemporary aesthetics, but what does it mean that they do?

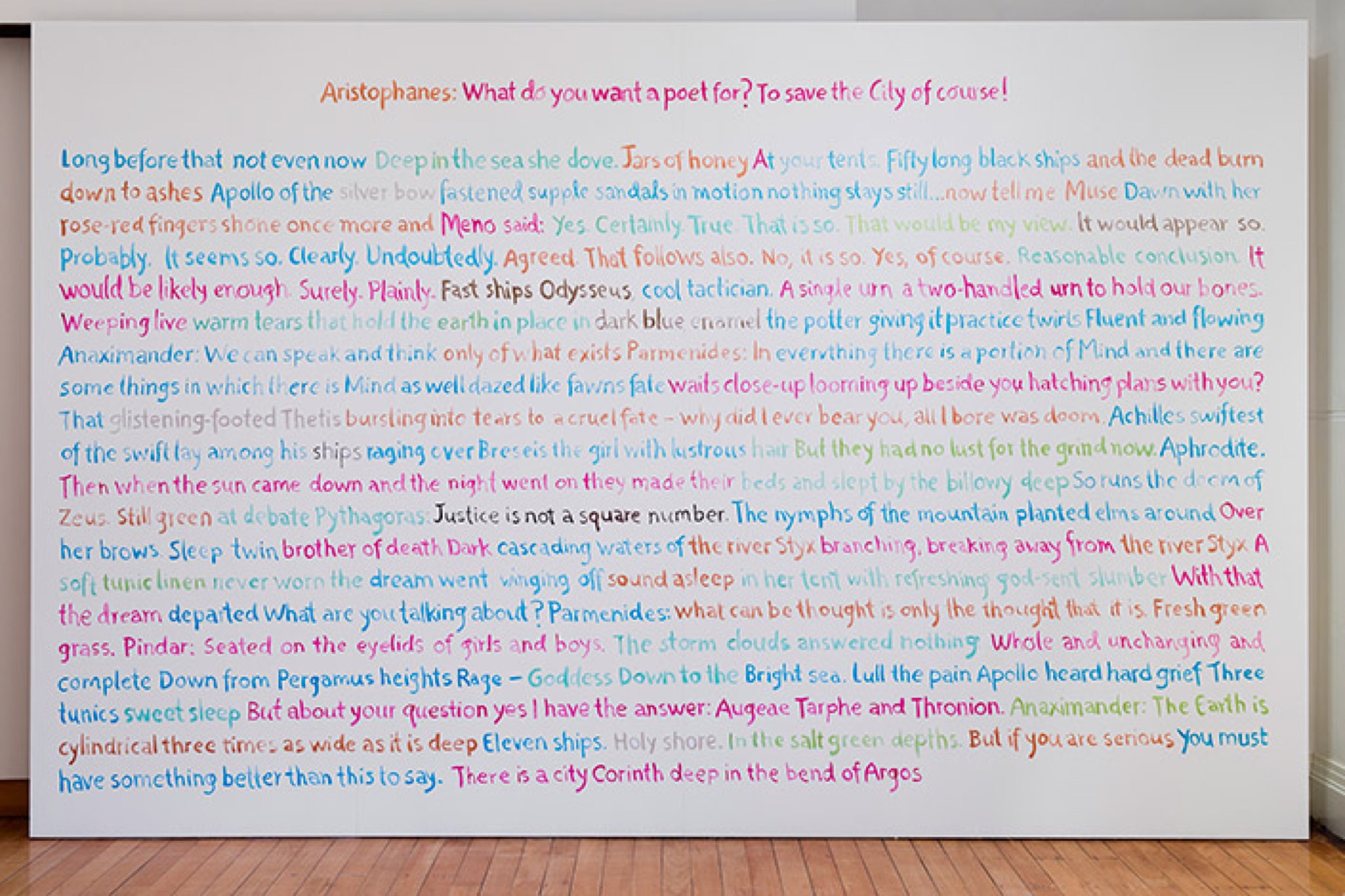

The exhibition has come from a fruitful collaboration between the artist and the Classics and Archaeology Collection, after a residency Brennan undertook with Sydney University’s Paphos Theatre Archaeological Project in Cyprus. Her treatment of this source material has yielded a response that traverses these histories and sites, the antique objects blending with Brennan’s own investigations into pottery and ceramics. A central source of inspiration for this exhibition is the Classics Department’s collection of lekythos vases, once used to pour ceremonial oils to honour the dead. These elongated forms are distinct from the rounded wine jugs and drinking vessels that also appear on display. Brennan has responded to the University Collection by creating contemporary versions of the Greek and Cypriot urns and vases, while also creating staging devices for the display of selected historical objects. Her examinations have also produced studies of the aesthetic and formal conventions of vase painting through drawings and sketches, as well as a line-up of printed tunics that hang against the gallery windows. A large wall painting, titled after a quote from Aristophanes’ 405 BCE comedy Frogs, arranges text and references to the figures and settings of well-known Greek dramas in a colourful weave of fragmented verse.

The display case facing the entrance boasts a colourful array of Brennan’s ceramic vases. Many of these generously shaped forms are topped with miniature figures that might represent the mythic personages that give the pieces their titles, such as Clio, Calliope, and the Naiads. On the opposite site, some of the classical pottery out of the University Collection has been displayed against a colourful cross hatched painted backdrop, adjacent to a further collection of Brennan’s own riffs on the urns and vases. Brennan’s ceramics are a joyful contrast to the historical objects, and her painterly interest in the bulbous orbs and stretched-out cylindrical forms of the antique objects is manifest in her own tulip-shaped, curvy variations. In one of the display cabinets, a collection of Brennan’s lekythos in smart pink and black decoration form a small cluster, while in another display unit an assortment of plates and a small population of miniature figures and vases are arranged as if in dramatic composition staged on an amphitheatre. On each of the plates, a short text with fragments drawn from theatrical dialogue has been painted, alluding to Socrates, Aristophanes, Apollodorus, and Eryximachus.

Continuing the theme, a series of tunics named after the Greek gods Pan, Pollux, Aphrodite and Athena are hung against the nave windows of the gallery. Emblazoned with drawings and prints that evidently depict the eponymous deity in question, the garments are backlit by the window, a little like stained glass illuminations. These vestments also contribute to the sense of theatricality in this exhibition: while they are good replicas of the tunics worn by the figures on the vase paintings, they might also reference the costumes for the tragic dramas and comedies referenced in the wall painting. A series of sketches, titled Vase Drawings, are displayed against the rear facing partition wall. These drawings look rather like concept sketches for the performance of a play; in one of the two larger prints the figures are engaged in dialogue, in the other, they perform Dionysian rituals. Michael Graf notes in his accompanying exhibition essay that, for the followers of Dionysus, the ritualistic consumption of wine to induce ecstatic states was considered a manifestation of the bond between the god and his devotees. The vases and drinking vessels such as that are on display in Forms of Life were also sometimes also buried with the dead as utensils for use in the afterlife.

As if forming a climactic apex to the exhibition, the colourfully rendered text decorates the farthest wall. The title of this piece, What do you want a poet for? To save the city of course! alludes to dialogue lifted from a play by Aristophones. Frogs was written in 405 BCE, just before the fall of Athens in the Peloponnesian war. In the play, Dionysus, the god of wine and theatre, has journeyed to the underworld to retrieve his favourite poet, Euripides. Dionysus becomes entangled in a contest between Aeschylus and Euripedes over who is the greater poet. As the battle for literary supremacy between the two playwrights wears on, Dionysus eventually sets a definitive measure: the best poet will be the one who can save Athens.

With this in mind, the collection of the historic objects, set against Brennan’s exuberant backdrops and her own ceramic studies, has the unexpected effect of being almost elegiac. The exhibition has the kind of bright, energetic vigour that seems befitting of a Dionysian revel, and it is in this joyful, celebratory mode that the exhibition reflects on the passing of an era. The staging of funerary urns and other quotidian vessels from antiquity feels like a theatricalized take on a civilization that is ultimately distant from our own reality. Brennan’s scenography stages the historical objects in equivalence with her own pottery, and it is this very correspondence between her vases and the antique vessels that I think emphasises the gulf between these contexts. Rather than showing how ancient motifs might resist periodisation, it feels to me that the effect is rather to affirm the passing of time as a certainty that connects us all.

Viewing the exhibition, I was reminded of a clip from American artist Shana Moulton’s video series Whispering Pines (2002-ongoing). In episode nine, Cynthia (a neurotic shut-in played by Moulton) watches a clip from the TV series Antiques Roadshow, where a Native American vase is appraised by experts to a value of $25,000. Cynthia notices an identical object in her own living room and this sets her off on a bathetic psychic journey that temporarily releases her from her confused and anxious reality.

In Moulton’s interior landscapes, ancient artefacts blend with gift shop knick-knacks and New Age trinkets. Back in 2010-ish when Post-Internet art was all the rage, and not yet an awkward term, I remember Greek vase painting and sculptures that mimicked ancient urns and pottery seemed to be a ubiquitous item of installation décor (Broodthaersian potted palms and ferns were the other omnipresent article). Mining antiquity for forms and shapes that might appeal to contemporary problems and questions doesn’t in itself ask anything new, or tell us anything different. But as Moulton reminds us through Cynthia, it does offer a kind of salve for our own present-day anxieties and frailties.

The question asked in the wall text painting, “What do we want a poet for?”, is an intriguing provocation. Frogs was written on the very eve of the fall of Athens. The answer, “To save the city of course!”, almost feels tragi-comic. The city could not be saved by the poets, and the disjuncture between the historical and contemporary objects on display here seems to be a marker of our shared temporal condition – we are all ultimately vulnerable to the passing of time. The display of these objects creates a kind of archaeological stage set, where it is as if we encounter a connection between antiquity and the contemporary as a theatrical concept. In this manner, Forms of Life proposes continuity of form not as an object of kitsch, retro fascination, but as a reminder of always being caught in time, and perpetually on the verge of disappearing.

Julia is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.

Title image: Angela Brennan, Forms of Life, installation view, Ian Potter Museum of Art. Courtesy Niagara Galleries, Melbourne and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Photo: Christo Crocker.)