Amrita Hepi, Monumental

Rex Butler

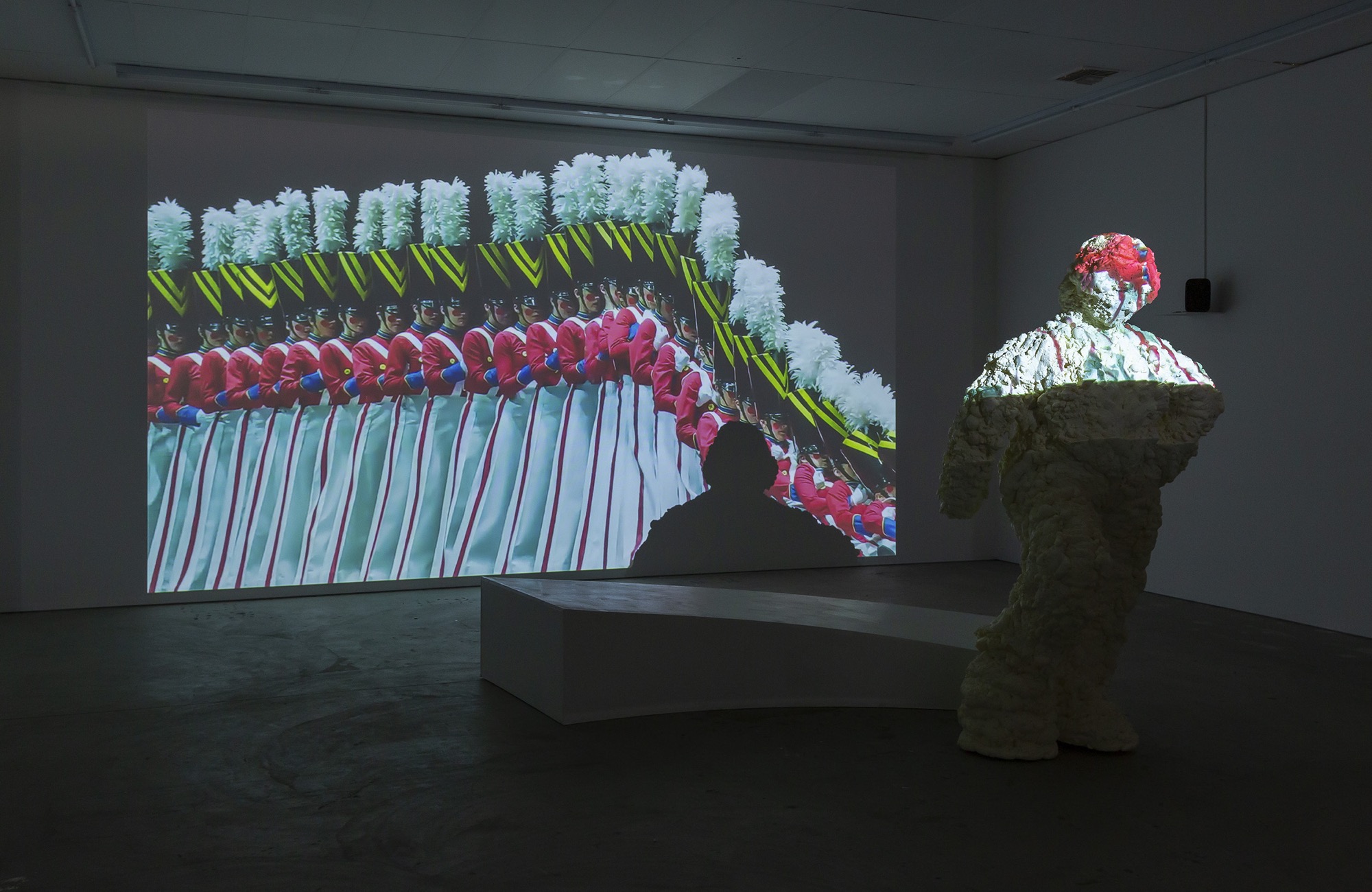

I got there late one Saturday, a week after it opened. In the room in which I sat to watch it the low afternoon sun streamed in through an open curtain from nearby High Street, casting my dark shadow up against the wall. On the wall of the gallery there is another sun, this time projected. Seven dancers hold still, five standing and two crouching, while behind them a white styrofoam statue stands atop a plinth, hips tilted and arm resting on its waist.

The previously still dancers come to life, moving sinuously and gracefully as they gradually uncoil in the manner of contemporary dance. They slowly grow more and more agitated, picking up a paddle and cricket bat and begin attacking the statue. It falls from the plinth to the ground under their blows and the dancers continue to pursue it, striking it again and again until it breaks up into little pieces. Then at the end, as the deep resonant synthesiser music rises to a climax and pauses, the dancers themselves take the plinth and adopt the poses of statues, while beneath them the pieces of broken styrofoam lie scattered on the ground, illuminated now by what might be a sunrise instead of the sunset of the previous colonial moment.

But actually I’m mis-narrating. It’s not as linear as that. From the very second shot of the video the dancers are furiously attacking the statue. At the end, after they have mounted the plinth, the whole video begins to reverse in fast motion, ending up with a shot from what might have been one of the original ships crossing the ocean to colonise the Pacific with another red sunset on the horizon. And throughout, interspersed among the dancing, there are shots taken from TV news reports of the Black Lives Matter toppling of statues from around the world, images of statues of Matthew Flinders wearing a COVID mask and James Cook splashed with pink paint and excerpts from the watery regimented dances of Busby Berkeley musicals and massive, almost cult-like variants of this from the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

It is Bunjulung dancer and choreographer Amrita Hepi’s Monumental (2020), and obviously one of the questions raised by the work is what exactly is the relationship between dance and the monument. Of course, the logic of classical dance is monumental, with the dancer in principle—this is the balance and poise at stake in the art—being able to break their movement at any point and hold their pose. Movement in classical ballet is precisely to be understood as a series of held poses strung together.

But then at some point in the late nineteenth century, encouraged by the advent of film, a revolution overtook ballet. Just as Eadweard Muybridge’s famous images of a horse in motion—the most naturally or unnaturally graceful of animals, as seen in all of the steps equestrian events put them through—revealed that it was not balanced and stable but seemed to stagger and stumble from one point to another, so contemporary dance does away with the held poses of classical ballet and instead seeks to capture those unbalanced and uncomposed moments in between.

Undoubtedly the great artist who captures all of this is Edgar Degas, who will in the same image paint young ballerinas at the barre, learning how to raise their ankle high to the side while remaining balanced on the other foot, undoubtedly encouraged to do so by the slap of the elderly ballet master’s stick, and other young ballerinas slumped exhaustedly in a chair, legs inelegantly askew and elbows resting on their knees. And then, in an extraordinary premonition of something like breakdancing, he will cast a woman on her back washing her vertical legs, in what must be considered a deliberate inversion of the logic of classical dance.

Hepi, in a 2019 interview to accompany a performance at the Melbourne Immigration Museum, speaks about how dance for her is fundamentally a group exercise and inseparable from the actual space in which it takes place, and in this it is exactly a refusal of the essential singularity of classical ballet (where there is always a lead dancer) and the idea that the space in which the dancer’s body moves is irrelevant (it is only given meaning or made visible by the poses that traverse it).

This is the real meaning of the anonymous communal dancing that takes place at the foot of the statue in Hepi’s work: it is already, before the dancers turn to attack the statue, unposed, unmemorable, unmemorial. It is not able to heroise or singularise the dancers’ bodies, hence all of those moments where they do the same thing, either in or out of sync with each other. Instead, Monumental brings out their anonymity, their indistinguishability, their continuity. (There is one moment where Hepi arcs gracefully through the air, but later this is reversed and we realise that it is only an effect of the video being run backwards.)

The body in classical ballet is always on a kind of plinth: elevated, separated, weightless and incorporeal, like those graceful mythical cygnets that scissor across the stage in every production of Swan Lake, able to be lifted effortlessly above their heads by the male ballet dancers (although, if you sit close enough to the stage, you can always hear the squeak of the ballet shoes and the subtle grunt of Siegfried as he strains to keep Odette above his head in the final scene).

The catalogue writer says a beautiful thing in the gallery flyer for Hepi’s video. “Monuments are dialectical”, they declare, in what could appear to be a classic example of artspeak but is actually very insightful. But how are statues “dialectical”? Put simply, it is because there is always a kind of split in them. This arises from the fact that, even though they single out somebody to stand alone or apart, understanding them as self-contained and self-defining, they can do so only because of a plinth separating them from the world. With the result that we can never exactly say what is part of the work or where it begins or ends. Or rather the work is self-contained but needs something outside of it for it to be so. And indeed we see this problem raised when we have to decide whether somebody is touching just the support of the sculpture or the sculpture itself or when the museum has to decide whether it can replace an ageing pedestal without affecting the sculpture itself. Again, it is not simply that the sculpture has no boundaries, but rather what allows these boundaries to be drawn also crosses them.

There is another Melbourne sculptor whose work reminds me of Hepi’s (for, of course, Hepi’s Monumental is as much a sculpture as a dance video): Callum Morton. One of Morton’s most revealing works is the set he made for a 2015 Melbourne Theatre Company production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, which simply repeated the space of the stage but opening up a door and windows onto it. As is well known, Beckett’s play constantly comments on the physical and theatrical limits of the stage as that “plinth” that separates the actors from the audience, with the actors often directly addressing the audience and thereby seeming to cross the boundary between the stage and the world outside. (In the simplest instance, they look at their watches to see how long the play has left to run, precisely collapsing the difference between the imaginary time of fiction and the actual time in which it is seen or viewed.)

Morton in fact did a set for an earlier Melbourne Theatre Company production, Jon Robin Baitz’s Other Desert Cities (2013) that might even have been a better fit for Endgame: simply the vitrine-like enclosed glass room of a modern house in which the action took place. Here Morton brought to its sharpest point the minute difference between the stage and the real world separated only by an invisible sheet of glass. The stage and the real world are the same (the characters of the play are based in part on identifiable American Republican politicians) and yet they are not, and the entire point of Baitz’s play is this minute “remark” that separates life from art. In a way, both Baitz’s and Beckett’s plays are “dialectical”, with each successive line spoken by the characters seeking to do away with either moral or artistic illusion, but only from another point whose reality and status is uncertain and will require another line after it to make clear.

Hepi’s work too is like this—and hence its complicated relationship to the real-world politics of BLM. It knows that for all of its attempt to tear down statues and erase monuments, it can do so only from a similarly monumental position. It is not real, but merely a representation. And there I was looking on at it from the outside, sitting on my own wooden seat casting a shadow. That is—and this is exactly cinema or video’s equivalent to a plinth—a necessary part of Hepi’s work is the spectator looking on at it from the outside. The work is projected up on the wall onto which the spectator looks. We might not only say that monuments are dialectical but also that Monumental is dialectical, forever split from itself and trying to make itself real.

The dancers in Monumental incessantly move between two points: they are at once inside the work as art and outside the work as real. And the white styrofoam statue that tumbles in Hepi’s video reveals itself as hollow, just as her own work reveals itself to be: emptied out or rather with its outside being inside so that it can declare its separateness from the world. And this is the true sign of its artfulness or status as art: the fact that it is no sooner finished than it has to start again. For just as Hepi brilliantly reveals the hollowness at the centre of both colonial power and the mounted statue, we would have to ask: from where is this spoken or said?

This is the profound truth of the BLM movement that Monumental is inspired by: that Black Lives Matter is more universal than All Lives Matter. This is not just because the questions of justice are much more pressing for black people than white people today but because black people have experienced much more directly than white people that loss or lack of identity that in fact precedes all identity, even a “white” one. As Les and Tamara Payne make clear in their recent book The Dead are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X, if Malcolm X at first espoused the Nation of Islam and a form of black superiority, he eventually gave both up and embraced a form of racial equality and non-specificity, understanding this as the prior condition for any personal identity. In effect, Malcolm X was asserting that everybody has an X in their name. Everyone is crossed out like he was before they can become who they are.

Morton has made a series of sculptures, the so-called Cover Ups of 2014, in which he cloaks notional public sculptures in a shroud or sackcloth. And though this excrescence is on the outside, it is really just the externalisation of that inner split between the sculpture and what it stands for.

Hepi does something similar in Monumental. If the dancers finally take the plinth in her work, it is not as one but as many, and this many is as much as anything the embodiment of the split within one. As she also says in her video for the Immigration Museum, for her dance is never for one but always for two. She can never make works individually, but only in collaboration with another.

Hepi, who is in fact both both Bundjulung and Ngāpuni Māori in origin, speaks of herself as “intersectional”, but I want to suggest that this does not mean that the two parts go together to form any whole. Not least because in contemporary Australia she necessarily dances with white statues. She moves with them and makes them move. Though they still remain on their plinths, they have now been brought down to earth, with COVID masks and pink paint. The only real monument now—which is exactly why Hepi calls her work Monumental—is the irreducible gap between the plinth and everything that tries to take its place. Statues become arbitrary, readymades, something momentarily holding a space, like a shovel or bottlerack, until something more universal comes along.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.