Aeon Resurrection

Tara Heffernan

The old centuries had, and have, powers of their own which mere “modernity” cannot kill.

—Bram Stoker, Dracula, 1897.

We live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind—mass merchandising, advertising, politics conducted as a branch of advertising, the instant translation of science and technology into popular imagery, the increasing blurring and intermingling of identities within the realm of consumer goods…

—J.G. Ballard, Crash, 1973.

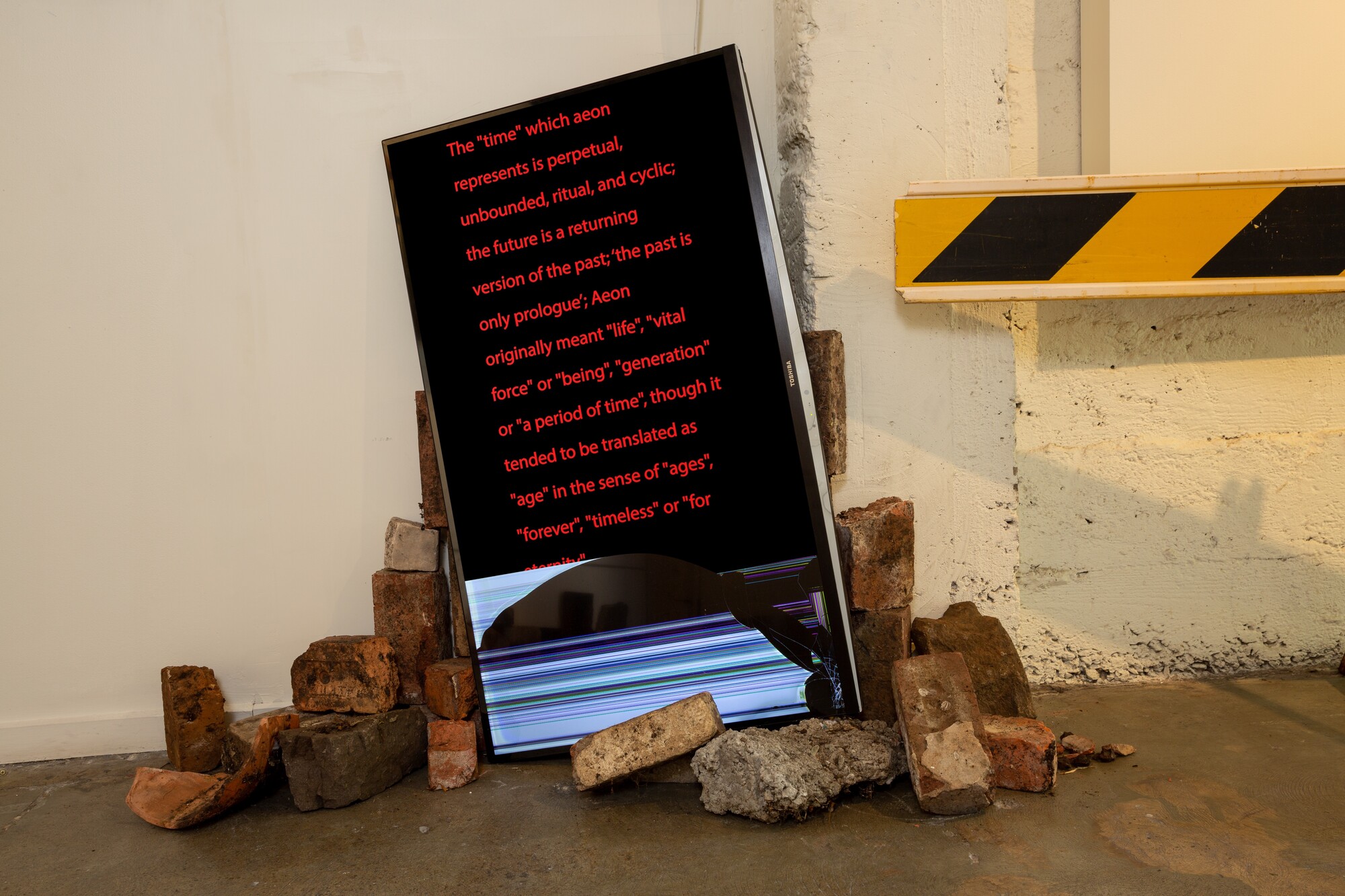

In 1929, the City of Essendon commissioned Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony, architects trained alongside Frank Lloyd Wright, to build an incinerator along the bank of the Maribyrnong River. Though the building’s purpose was to house furnaces to burn the city’s waste, their aim was to create a beautiful yet inconspicuous structure. As Griffin summarised, “the final test of modernism is the replacement of industrial eyesores”. Decommissioned in 1942, the building remained empty until the mid 1980s when it became a hub for arts organisations. Today, its aggressive asymmetry houses Incinerator Gallery, a startlingly contemporary art space for the quiet western suburbs. Aeon Resurrection, curated by Jake Adam Treacy, is a poignant exhibition for the space. As explained in the curatorial text scrolling on a smashed monitor by the entrance, the exhibition explores “collective and rhizomatic future-making” as a means of imagining “reality beyond the human in the crepuscule aftermath of apocalypse”. The exhibition title is spray-painted in messy red letters across a crumpled plastic sheet strewn above the entry, haloed by barbed wire. As the architects intended, the chic modernist container conceals the chaos within.

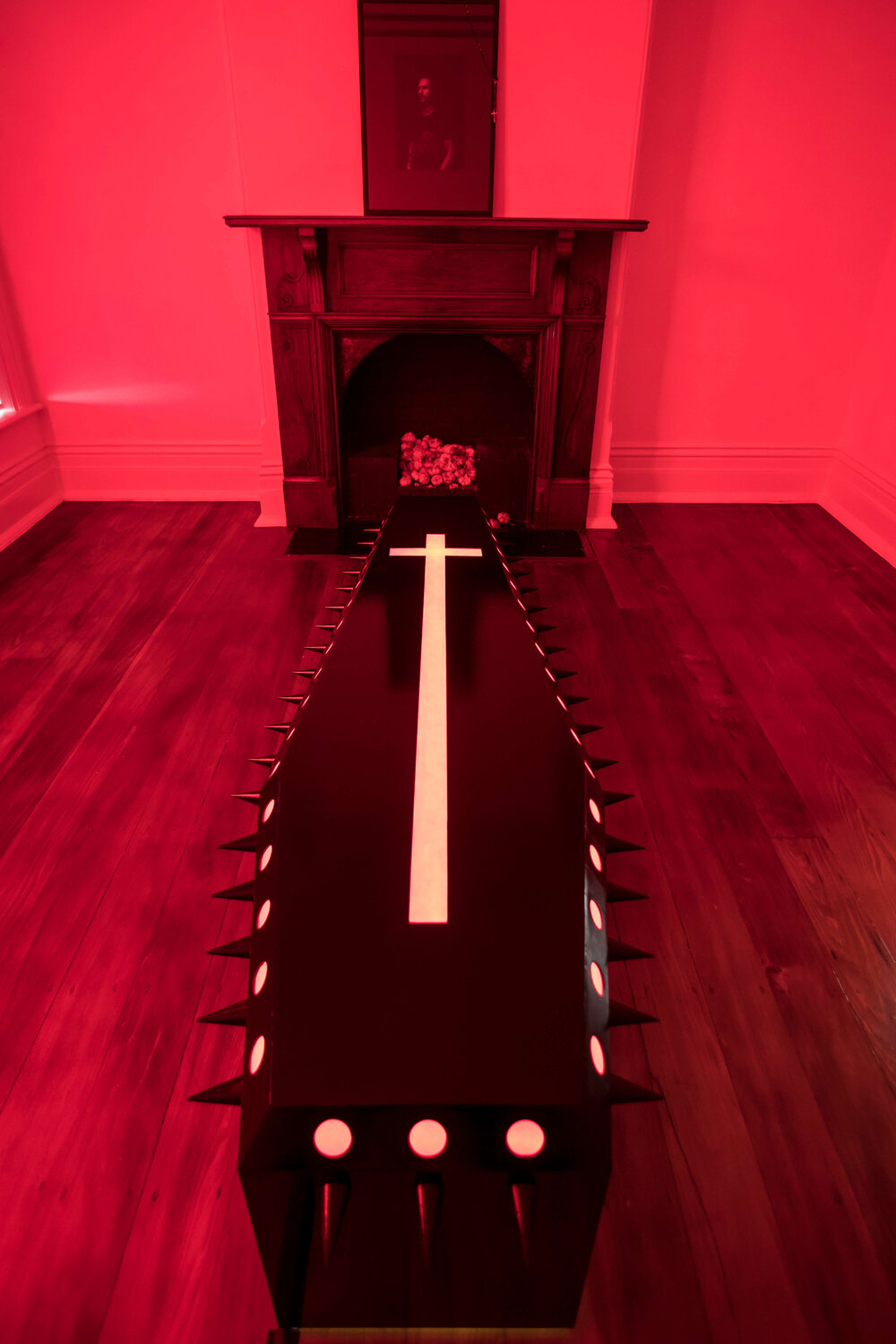

This crepuscular aesthetic is carried throughout the exhibition, which is housed on the upper level of the building. The artworks are punctuated by elaborate props that create an immersive atmosphere. In the open-plan space, you’re confronted with a neon emblazoned coffin lined with spikes (by Diego Ramirez), a tapestry of the grim reaper riding a giant dribbling dick dinosaur (care of Nicholas Aloisio-Shearer), roadblocks, scattered bricks, shreds of black plastic and tattooed oranges pierced with burning incense (part of an installation by Em Finucane). It’s difficult to assess the vibe cultivated by the artworks and elaborately curated art-mess. It might be best described as an abandoned Church occupied by pagan squatters with interior design degrees crossed with a macho, incel-adjacent gamer dungeon.

Scattered throughout the space are giant sheets of opaque plastic, of the kind that might be used to line the floor during a messy building renovation or a well-planned homicide. Exposed extension cords and powerboards litter the corners of the gallery floor—an exposure that might be interpreted as reflecting on the constructed nature of art and the mechanisms behind it that are often concealed by white-walled galleries. However, this look is also entirely congruous with the messy, DIY feel of the show. The chaotic pastiche of barbed wire, steel scaffolding and bricks seem to reference urban bondage and restraint: the iconographic and physical barriers that are erected in dangerous, decaying sites in a desperate and often futile attempt to hold things together and keep people out. In a sense, the whole gallery is a danger zone—a site that flirts with indulgence in the id. In the array of works, which explore avatars, costume, body modification and hidden cultural knowledge, we find an astute and multiplicitious examination of ways of being—or coping—in a chaotic technoculture.

The navigation of virtual space and its ambiguous relation to “real life” is a recurrent theme in the exhibition. The work of Huntrezz Janos and Jahkarli Romanis explore different facets of this dynamic. Romanis’s work explores her identity as a Pitta Pitta woman. Displayed on a monitor mounted on the gallery wall, visible when you take the first corner from the entrance, Cache (2022) adeptly applies the conventions of post-internet video art to highlight the disjuncture between the sites deemed significant by capitalist, ocular-centric technoculture and Indigenous knowledge. The three-minute video intercuts glitchy, pixilated images of Pitta Pitta country (North-West Queensland) taken from Google Earth with flashing photographs of the landscape. Romanis’ is one of the quieter works in the exhibition, providing a sombre meditation on the ambiguity between technology and memory.

Huntrezz Janos’s work is comparatively loud. Projected onto billowing sheets of fabric concealing the far-left corner of the gallery space, beneath which a neon light tube rests shrouded in plastic, Janos’s animation video (2022) displays a range of jacked, ambiguously gendered avatars that resemble fashion label Balenciaga’s monstrous posthuman aesthetic. Janos is a trans-fem Afro-Hungarian multidisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles and Budapest, though lives, according to her bio for the 2021 Athens biennale, “mostly in the metaverse”. Her work in Aeon Resurrection reflects this investment in online living. As the wall text explains, in Janos’s practice, avatars serve as a form of “self-expression” deployed to “overcome dysphoria often encountered in the ‘real world’”. This desire is obviously shared by many, considering the ubiquity of online gaming addictions and the rising popularity of virtual reality porn since the mid-2010s. Another work, face filters (2022), is presented on iPads alongside the animated avatars, displaying face filters designed by Janos, which are available for use online.

Janos’s bio summarised her work as a “bold abandonment of physicality” and a “slap in the face of the seriousness of performance art, the perspiration and the exhaling of self-importance”. Rather, Janos’s work apparently heralds “a new breed of art persona that is boldly superficial”. While bold superficiality is the new norm as global citizens compete online, doing their best to manipulate the algorithm for love, attention and economic rewards, we should remember that we don’t live in a posthuman world yet. During the Covid-19 lockdowns, minimum wage front-line workers such as nurses, health-care professionals and those in the highly exploitative service industry risked their health during every tedious working hour, sweating under their personal protective equipment. All the while, members of the professional class—those that drive cultural discourse—were working from home on their laptops and sharing bread recipes via social media. As Romanis’s video work emphasises, the metaverse might leave things and people behind, replicating IRL hierarchies. Perhaps only the elites can abandon physicality?

A number of other works approach more IRL friendly explorations of identity and self-expression. For example, fantastical alter-egos borrowing from queer ancestorial myths reign in a dusty-pre-civilised—or post-apocalyptic—landscape in Justin Shoulder’s video-work AEON†: EP I (2020). In a similar gesture, Ange Jeffery’s brass breastplates Brothaboy Sistagirl (2021) celebrate the interchangeable use of these gendered terms in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Across one wall, a series of concrete poems curated by Melbourne collective Thin Red Lines offers a respite from screens, lights and charged imagery.

Perhaps the most confronting work in Aeon Resurrection is a full-body latex skin suit, tattooed with floral patterns by local artist Em Finucane. Suspended from the roof by chains that tent the deflated body in odd places, The Body as a Space we Inhabit (2019) resembles a crumpled, discarded human snakeskin. It has life-like hands and feet that dangle limply displaying bright neon nails. Creating a square formation below the suspended skin are four oranges pierced with incense sticks, sitting atop structural anchors (large metal pins used in construction). This arrangement references a ritual Finucane’s mother would perform when the family moved into a new home to let the spirits know they would now be sharing the space. A recording of her mother explaining the ritual in Cantonese emanates from a speaker nearby. In this artwork, Finucane conflates the skin and the home as spaces we temporarily inhabit.

Presumably inadvertently, the headless skinsuit recalls a crime-scene photograph from the property of infamous American murderer Ed Gein. Displaying the decapitated body of Gein’s final victim Bernice Worden, the black and white image reveals the inverted silhouette of a female form strung upside-down and dressed out like a deer. Among other famed characters, Gein served as the inspiration for Jame Gumb/Buffalo Bill, the serial killer antagonist in Thomas Harris’s 1988 novel The Silence of The Lambs. The book and later film adaptation focus on orality—on mouths, lips, teeth, chewing and spitting. Cannibalism serves as a metaphor for desire and its inherent animalism. After a lifetime of neglect and abuse, Buffalo Bill’s self-loathing leads him butcher and flay women with the plan to create a woman-suit from their skins—a direct reference to Gein’s obsession with his dead, overbearing mother and his attendant necrophillic practices. Director Johnathan Demme explained the motivation as follows: “by turning himself into a female, then surely Gumb can feel like he has escaped himself”. While binary-thinking liberal leftists fixate on how Buffalo Bill might mis-represent trans people in popular culture (though it is explicitly stated in both the book and the film that Bill isn’t trans), the theme lies with the desire for escape through radical transformation. This concern is echoed in Aeon Resurrection, where the curatorial choices appear to flirt with a cultish, serial killer aesthetic as a subversive metaphor for transcendence. To me, Finucane’s skin suit seems testament to the inconsolable agony of corporeal experience—of being trapped in a body that can betray your inner desires.

Diego Ramirez’ Eternal Arrival (2019) also borrows iconography of the horror genre, albeit in a campy guise. The glossy coffin-shaped lightbox is accompanied by a neon drawing titled Infinity of the Past (2019), an appropriation of the Mayan symbol for Camazotz—a bat god associated with the death, sacrifice and the night. For Ramirez, the vampire is significant as an allegorical figure for migration and otherness who has attracted, in various cultural iterations, the anxieties of different eras. In this installation, Ramirez plays upon these hybrid associations and their nuanced relationship with power, desire and fear. The glowing coffin is replete with embellishment, including studs that might resemble crenelated castle walls or spikes common to BDSM apparel. Ramirez’s attention to detail—the indulgent gothic gaudiness—demonstrates his deep investment in this visual language. It is also suggests a rather contemporary “goth” interpretation of the vampire that has been filtered through twentieth-century media. As Ramirez notes in his essay ‘Unnatural Hunger: the copy, the vampire, and postcolonial anxieties’ (2019), the racial coding of the vampire inherited aspects of the Latin Lover stereotype of early twentieth-century Hollywood, namely the slicked-back hair and tuxedo—a precedent set by Todd Browning’s influential 1931 adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Here, Dracula—as a racialised, provincial foreigner that seduces and corrupts white women—embodied anxieties about the migrant’s corruptive influence and jeopardisation of resources in a xenophobic, depression-era America.

Indeed, part of the fear of the other is the belief that the other steals pleasure from us—that they have access to something that we don’t, and revel in this surplus. However, vampires are particularly hot in media. The cuck fantasy is a real crowd pleaser. Before Bram Stoker’s interpretation, the vampire was a walking corpse, rather unsexy. Ruddy with vitality, to paraphrase Stoker, Dracula was the first “undead” vampire, perpetually alive, but too alive. There is an overwhelming too-muchness to his desire, which manifests in the vampire’s “insatiable hunger”. This imagined, ultra-sensuous other becomes a site onto which to project our own violent, repressed desires—we delegate pleasure to them, making them a channel for our own libidinal energy. Therefore, the fantasy of the other’s inherent difference and attendant access to pleasure—which elicits hate, envy and arousal—is upheld partly to justify this projection. With its neon lights and glossy finish, Ramirez’s souped-up coffin speaks to the fantasy of this forbidden, perverse excess and its commercialism. There’s no body in the coffin, living or undead. It’s a flashy prop that fuels our horny imaginings.

Speaking of commerce, an intriguing aspect of the vampire as an othered figure is his relationship with power. Dracula isn’t a rough but an aristocrat who takes control of bourgeois characters as a means of satisfying his territorial expansion. His appeal—and that of many subsequent filmic vampires—is located in his refinement and otherworldliness against the dreariness of everyday people, mesmerising middle- or lower-class subjects who are tethered to their class, race and ways of being. In the Twilight series, for example, Edward Cullen is a glittery beacon of mystic otherness against the dullness of white suburbia. The spectacle of Ramirez’s installation seems to signal the cultural currency of otherness and the theatre of aesthetic coding that accompany articulations of difference—a particularly pertinent point in a liberal image culture obsessed with sucking the lifeblood out of “diverse” identities and accentuating signs of difference.

Quite opposed to the alluring mystique of the vampire, the most unrelentingly grotesque apparitions in Aeon Resurrection appear in Nicholas Aloisio-Shearer’s tapestries. Created via digital imaging software and a computerised jacquard loom, these tapestries appropriate, alongside historical and biblical references, the iconography of a lowbrow and coarse contemporary masculinity forged in regressive online environments. Each of the tapestries is supported by resin appendages sourced from a 3D-printing repository of sex toys. The series Reject Modernity, Embrace Tradition II: I Have Been In This Place Before (2021), which confronts you at the first turn from the gallery entrance, takes its name from a popular meme with a reactionary origin: the unfavourable comparison between a current phenomenon and its historical precedent. In these memes, contemporary art is often the target. One work in the series references Jan van Eyck’s Fountain of Life from his Ghent Altarpiece (ca. 1432), but instead of eternal salvation Aloisio-Shearer’s fountain features demon mouths projectile-vomiting blood between them in a perverse, orally fixated cycle. Apparently, this work was partly a response to the proliferation of memes about spitting in mouths. Aloisio-Shearer had become suspicious that such an act “was now a mundane way of interfacing with other people”. Indeed, the memeification of hardcore porn tropes might be a symptom of the constant churn for new and improved deviancies in a hypersexualised/hyperdesensitised age.

When appraising his art, you must appreciate that Aloisio-Shearer employs as many cultural reference points as a typical normie-hating nerd—a testament to his grasp of the bodies of knowledge fostered by the combination of excess and insularity that characterises the manosphere. In a particularly explicit tapestry, a grim reaper donning an Ahegao hoodie rides a giant bipedal dick. He wields the spear of Longinus as it appears in the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion. The cock-monster, whose form has been appropriated from a 3D print repository for sex toys, has tiny arms and strong legs like a T. rex. The Ahegao hoodie has associations with involuntary celibates or incels—men that harbour intensely hostile feelings towards women due to their real or perceived exclusion from dating and sex. What Aloisio-Shearer appears to present is a nightmarish and tyrannical image of masculinity—the reviled, sex-obsessed incel as death, or a harbinger of the apocalypse. However, rather than a targeted critique of male aggression, Aloisio-Shearer’s incel might embody the horror of the present. A scapegoat for our individualist culture, the incel could be interpreted as a casualty of downward mobility in a hypercompetitive, neoliberal age; this is brilliantly illustrated by the proto-incel protagonists of Michel Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998). Though they sometimes try to argue to the contrary, the incel belongs to an identity category that cannot claim any empathy points under the neoliberal tally system of “-isms” used to qualify hardship. Their whiteness and heteronormative maleness make them the perfect subject to absorb hatred and disgust from an openly cruel and righteous liberal culture indifferent to the devastating impact of growing economic inequality.

In the context of Aeon Resurrection, Aloisio-Shearer’s compelling work seems to provide a foil. His hybrid appropriation of memes and iconography common to regressive internet cultures parallels the interest in avatars and countercultural investments of the other exhibited artists. However, Aloisio-Shearer points to the inverse of the politics of desire and self-fulfilment. The practices he references don’t recoup a value in progressive political rhetoric and are not celebrated for their emancipatory potential in the metaverse. As cultural theorist Angela Nagle has highlighted, the manosphere taps into earlier manifestations of sadism, comparable to the libertine hedonism of Marquis de Sade. Perhaps their transgressions might reveal that the true indulgence in base desire may come at the cost of others.

The rhetoric put forward by the curatorial narrative, of the rhizome, the potential in destruction, posthumanism and apocalypse (an aesthetic capitalist shadow of revolution), appears to embody a continuation of the liberal left’s investment in transgression and unbridled sexuality that began in the 1960s. Compounded by the muddying impact of postmodern plurality, the exhibition spectacularly reflects the dissolve between political discourse and role-play heralded by a capitalist technoculture obsessed with image-production and delegated experience—a dissolve that has manifested on both the right and the left. Perhaps one tendril of the rhizome stops here; no one political persuasion holds a monopoly on self-expression or desire. We are all desiring subjects seeking transcendence.

Tara Heffernan is a blind art historian currently completing a PhD (Art History) at the University of Melbourne on the work of post war Italian artist Piero Manzoni. Her academic work focuses on global modernism and the avant-gardes with an interest in their ongoing aesthetic and political relevance to contemporary debate