A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness

Anna Parlane

The current exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness, is very welcome. This is in part because it is the inaugural product of an institutional and governmental investment in not only Indigenous artists but also Indigenous curators. A partnership between Creative Victoria, ACCA and TarraWarra Museum of Art, the Yalingwa initiative supports substantial artist fellowships as well as curatorial work for a series of three commission-focused exhibitions. Curator Hannah Presley’s A Lightness of Spirit provides a strong start to this series.

ACCA’s programming has taken a distinctly political turn under artistic director Max Delany, and the gallery’s participation in the Yalingwa initiative begins to make good on the promise implicit in the 2016 exhibition Sovereignty. Co-curated by Delany and Paola Balla, Sovereignty opened the gallery up as a forum for Indigenous talent and leadership. Delany described it as the ‘first step’ in a longer term project of engagement with Aboriginal communities. Presley’s appointment as ACCA’s first ever Indigenous curator seems like the next step in this direction.

Presley’s exhibition is additionally interesting because of its surprising—and I think strategic—reorientation away from contemporary Indigenous art’s long-established association with the language of protest. Where Sovereignty traced a genealogy of the intertwining of art and activism, Presley’s show is an intimate and upbeat look at humour, family and togetherness. This focus in no way denies the horror of this country’s (ongoing) colonial history, but instead chooses to celebrate resilience and humour as a means of survival. This is a fine line to walk, and it is a testament to the sophistication of the artists’ works that the exhibition succeeds in walking it.

All the works in A Lightness of Spirit are new commissions except for one, which provides the show with a central reference point. This is the charming short film Never Stop Riding, 2017, a tongue-in-cheek Spaghetti Western made by Alec Baker, Peter Mungkuri and Mr Kunmanara Pompey, three senior men and former stockmen from Indulkana in the APY Lands. While the filmmakers (and actors) clearly had a lot of fun making this film—there are some lovely moments of levity—the cinematography is also sometimes genuinely lush. We are treated to lingering shots of expansive desert horizons, brooding close-ups of the protagonists’ faces (complete with tough-guy stubble and cinematically narrowed eyes), and riders galloping in slo-mo, silhouetted against the golden light of the setting sun. It’s classically, gorgeously romantic, and absolutely cognisant of this fact.

By taking the Spaghetti Western formula—itself already an appropriation of the Western genre by Italian directors—and importing it to Indulkana, Never Stop Riding remobilises the stereotype of the US cowboy to stunning and comedic effect. A representation of heroic masculinity that seems so hackneyed as to be unredeemable—the stoic, good-looking man of the plains, rendered gritty and tough by his uncompromising moral code and his profound attachment to the land—is reconfigured in Never Stop Riding as a portrait of the Aboriginal Australian stockman. The cowboy image and its attendant mythology of emplacement was a way for settler culture in the US to stake its claim to land stolen from the Native American tribes. There is a certain satisfaction, then, in seeing this image so wittily re-appropriated as an assertion of proud Indigenous identity.

The most interesting aspect of Never Stop Riding, for me, is the way that it uses the stereotype of the cowboy to its own ends, effectively incorporating this image into a distinctively Aboriginal worldview and thereby completely revising it. This is also a feature of all ten of the exhibition’s commissioned works. In addition to Presley’s core themes of humour and community, every artwork in the show is attentive to processes by which cultural material can be incorporated or remobilised in a different context.

Vicki Couzens’s installation, Djawannacuppatea, 2018, is a teapot-shaped stage set for the domestic ritual of sitting down together for a cuppa. Best known for her work reviving the practice of making possum-skin cloaks, Couzens’s installation examines tea-drinking as a setting for familial and community intimacy, as well as inter-generational knowledge transmission. Far from regarding tea-drinking as a colonial imposition, Couzens firmly locates it at the heart of contemporary Aboriginal family and community life. Her title is a case in point: by running the words ‘do you want a cup of tea?’ together, Djawannacuppatea jokingly claims the question for Indigenous culture.

Works by Jonathan Jones and Robert Fielding also attend to ways in which cultural forms are transformed, recycled and revived. For Fielding, the way that colonial-era objects like the Jackaroo flour tin were repurposed in domestic settings—as storage tin, bucket or furniture—triggered a series of reflections on how objects straddle past and present, and how reused or recycled objects carry their earlier uses and the touch of ancestral hands into the present and future.

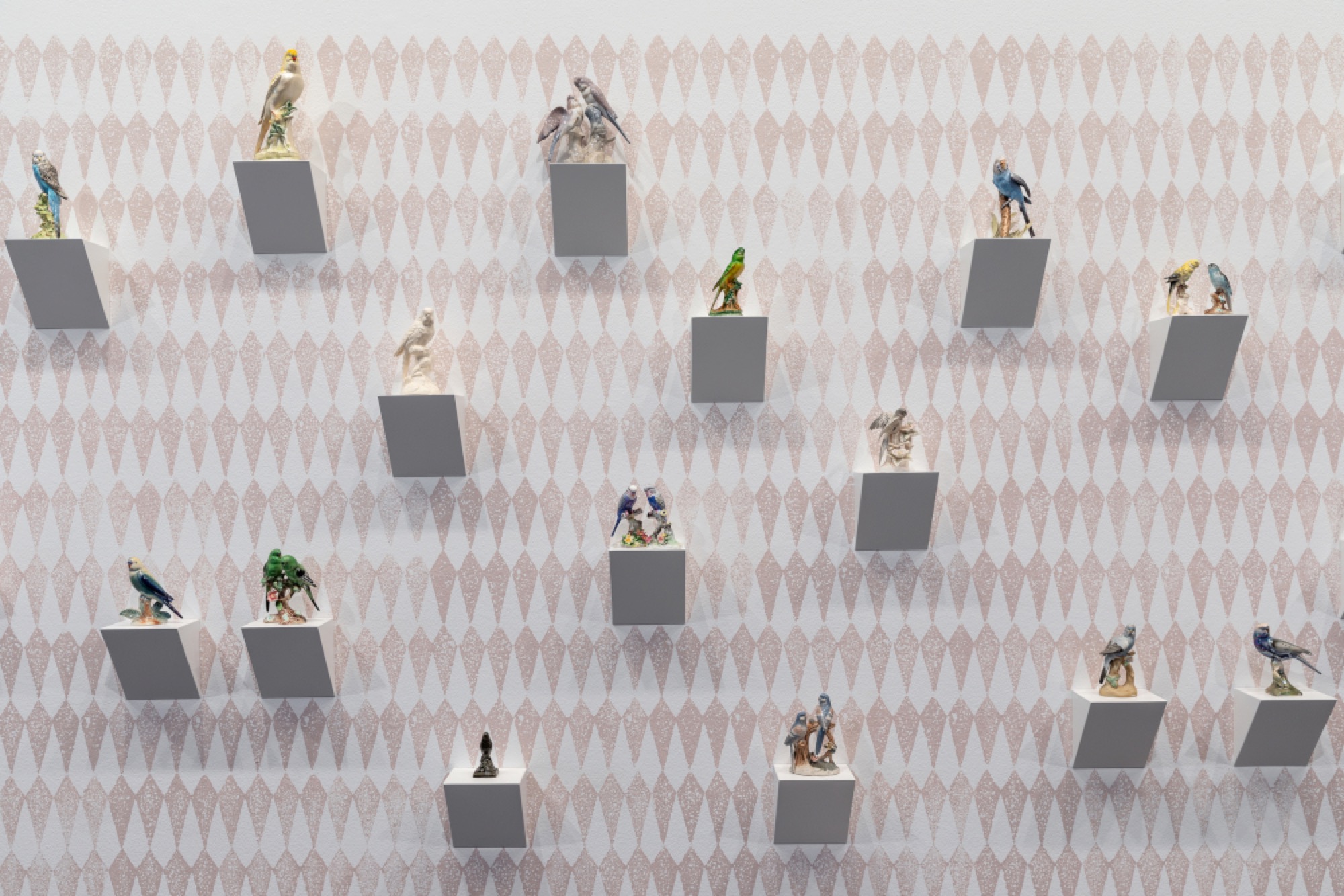

Jones’s untitled (gidyirriga), 2018, takes the figure of the budgerigar as emblematic of dynamic processes of mutation and change. Budgies are apparently the world’s third-most popular pet, and their popularity has led to a massive diversification of the bird’s appearance through breeding. Just as most contemporary budgies look dramatically different from the original Australian native parrot, Jones points out that the name ‘budgerigar’ is a mispronunciation of the bird’s original Wiradjuri name ‘gidyirriga.’ His collection of mass-produced porcelain budgie figurines subtly refer to the way that the porcelain casting process reproduces and magnifies any defect or idiosyncracy. The work’s examination of how deviation is built into processes of repetition is underscored by a soundtrack of school children chanting ‘gidyirriga! gidyirriga! gidyirriga!’ as they learn to speak Wiradjuri.

Kaylene Whiskey and Vincent Namatjira’s vivacious and quick-witted paintings both incorporate international celebrities into local settings. In Whiskey’s Seven Sistas, 2018, pop icons like Michael Jackson and Whoopi Goldberg become a local pantheon, guest starring in the creation story of the Kungkarangulpa (also known as the Seven Sisters or Pleiades) constellation. Namatjira’s Welcome to Indulkana, 2018, is a triple portrait showing the artist cheerily waving the Aboriginal flag out the window of Albert Namatjira’s famous green ute while flanked by Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. By relocating these two controversial figures to the APY Lands, Namatjira noted that ‘They’re here on my terms and I’m taking away some of their power.’ While his painting appears light-hearted - and it is very funny - Namatjira’s comment makes the politics of his strategy clear.

A similar politics is at play in Never Stop Riding. It would be entirely possible to interpret this work in relation to other contemporary re-runs of the Spaghetti Western formula, like the films of Quentin Tarantino for example. However this would miss the most important and interesting thing about the film, which is its Aboriginality. It is more productive, I think, to compare the film to works like Gordon Bennett’s Self-Portrait (But I Always Wanted to be One of the Good Guys), 1990, with its dualistic ‘Cowboys and Indians’ imagery. Postmodern appropriation provided Bennett with the artistic language to speak about a hollow and fundamentally incoherent Australian nationalism predicated on the erasure of Aboriginal peoples, cultures and histories; and simultaneously about the original repression of his own Indigeneity. His works speak in a self-consciously double register, and their power and rage emerges precisely out of the incommensurability of these layered narratives. Never Stop Riding, and the other works in the show, lack the disjunctiveness that is the central characteristic of appropriation art like Bennett’s. What appropriation holds distinct, these artists run together. In doing so, they enact a process of making-familiar which acknowledges how all practices, traditions, images and mythologies take on local meanings and become incorporated into local life-worlds. In A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness, this dynamic flexibility is a form of resilience but also an expression of agency.

Anna Parlane is a writer and occasional curator based in Melbourne. She is currently finishing a PhD at Melbourne University, and was previously assistant curator at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Title image: A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness 2018, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.)