David L. Johnson

Artist David L. Johnson condenses centuries of enclosure into “Diggers,” repurposing hostile urban fixtures as provocations against privatisation, surveillance, and racial capitalism.

The enclosure of the commons—land traditionally held and used by the public—began in medieval England, and has continued ever since. In his 2014 book Stop, Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance, American historian Peter Linebaugh contends that the enclosure and privatisation of the commons was inseparable from England’s industrialisation, as well as the development of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. In other words, enclosure played a foundational role in the rise of racial capitalism—a global system of value extraction and capital accumulation dependent on what abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as “the state-sanctioned and/or legal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death.” Linebaugh identifies three major waves of enclosure.

Exclusive to the Magazine

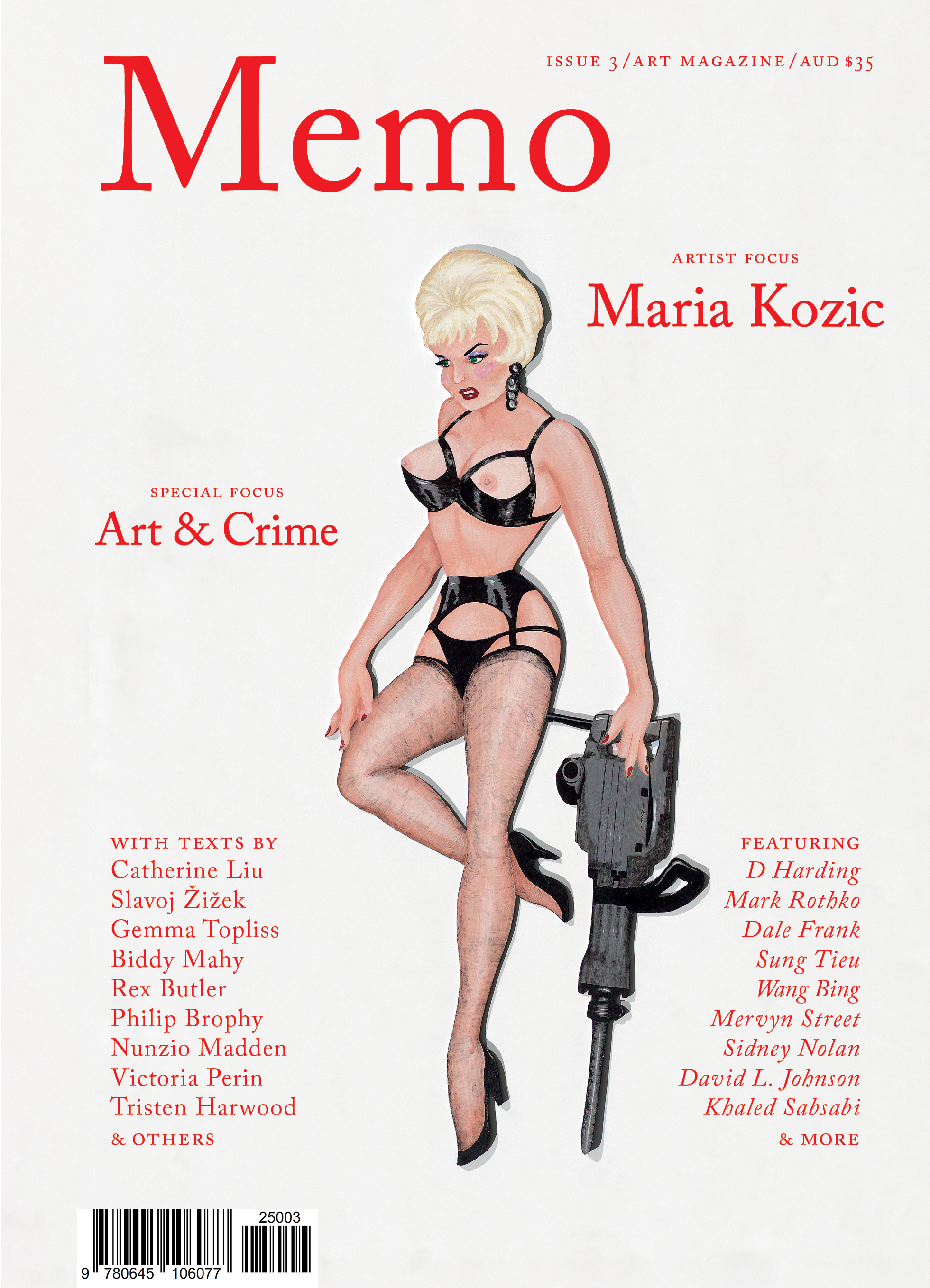

David L. Johnson by Dana Kopel is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

“It is no longer my face (identification), but the face that has somehow been given to me (circumstantial possession) as stage property.” — Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Omnicide: Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium

I have begun to desire noise. Noise that prompts. Maybe wounds. I want to remember something that feels tangible, and if I have no memory of how this feels I want to create one.

As Melbourne’s art institutions blur the line between art and design, a corporate logic of spectacle, lifestyle, and marketability takes hold. Is the NGV’s embrace of design a progressive expansion—or just kitsch in highbrow drag? And if public museums have abandoned art, who’s left to protect it?