Art Against Contemporary Autocracy—Australia Included?

Artistic resistance, from Ai Weiwei to Archie Moore’s kith and kin, punctures the facades of power as Australia’s art institutions wobble between defending creative freedom and capitulating to a rising culture of control.

Black shirt in the White House: X Æ A-Xii Musk, Elon Musk, and President Donald J. Trump at a press conference in the Oval Office, White House, Washington, introducing the Department of Government Efficiency, on February 11, 2025.

Suppose we understand authoritarianism as the rule of a single leader or party that deems itself infallible, even when it changes its mind, policy, or method, and imposes that will upon its subjects. If that’s the case, we can chart a long history of artists accommodating themselves to such rule, evading it, or resisting it. In recent years, however, authoritarianism has exhibited some novel features—while continuing its totalitarian thrust. What has changed? What kinds of resistance might the visual arts, including its history, offer in the new circumstances? I honour all those artists, writers, and thinkers—in fact, every individual, group, and organisation—who have stood against authoritarianism in whichever ways they can. I thank them for my freedom. I have visited some autocracies, but never lived in one—at least, not yet—so I can speak about strategies only as an outside observer and offer tentative suggestions, as the situation is so transitional.

The death notice for modern authoritarianism was meant to be served around 1990, as the Berlin Wall fell, and the Soviet system imploded. Hopes that the “actually existing socialisms” were harbingers of historically inevitable communism finally evaporated. The triumph of democratic freedom was announced: free elections, free peoples, free markets, free trade, free thought, free connectivity, free world. Instead, neoliberal globalisation sought command of economies everywhere. In geopolitics, “the rules-based order” mostly followed the interests of the United States hegemon; in national politics, democratic representation was constantly compromised; in culture, local flourishing within multiculturalism battled nostalgic reaction and fundamentalism; in the arts, free expression and transcultural exchange contrasted with a booming market for a narrow band of luxury art; and in everyday life, individuality struggled within hyperconnected, information-overloaded, commodified spectacle. Our task as artists, thinkers, and world beings has been to promote what was liberating in this mix and to critique its closures, exploitations and inequities. One generation later, this picture of how power really works in the world—at large and in the details of everyday life—has reached the limits of its capacities and run up against other, increasingly powerful pictures, most of them recursive, many of them autocratic.

The 2025 report of the Varieties of Democracy Institute at the University of Gothenburg is entitled 25 Years of Autocratization—Democracy Trumped? Its key finding is that nearly three out of four people alive today live in autocracies. While some countries (nineteen) are democratising, many more are autocratising (forty-five). Liberal democracies are the least common regime type. V-Dem notes that the favourite weapon of autocracies is media censorship, followed by undermining elections and civil society. Previously existing autocracies have not hesitated to add outright repression to this list, suppressing the Arab Spring and democratising movements in Russia, Myanma, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Nicaragua, Hong Kong, and elsewhere. Extreme right-wing parties are attracting growing support in long-term democratic countries, not least in Europe. In the United States, especially with the second Trump presidency, they have taken power. And they are uniting to form a geopolitical axis while partnering with the “new tech” overlords.

From a planetary perspective, all kinds of regimes can exploit the information networks that now govern many interactions between living beings, institutions, machines, and the biosphere. Changes in geopolitical formations may split these networks into a “Silicon Curtain” between the firewalled networks established by the US and China, or between several, if other “developing nations” follow the Modi model of techno fundamentalism. They may also be subject to the accelerating capacity of AI to generate its affordances. In his Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI (2024), Yuval Noah Harari argues that, while technically non-ideological, AI algorithms favour the centralised power of autocratic rule and monopoly capitalism. But mostly, they favour their own perpetuation and expansion.

Visual artists and all who support them have inherited several ways of resisting the swallowing of their freedoms. Symbolic Contestation is the most common and most internally varied. Artists often conceive of visual figures that condense information that repressive authorities wish to distort or hide. In his work Snake Ceiling (2009), Ai Weiwei configured hundreds of children’s backpacks into the free-form shape of a snake to commemorate the living memory of the more than five thousand killed in the 2008 Szechuan earthquake. A more concrete evocation is his Straight (2008–13), an installation of steel rebar recovered from the collapsed schools. Corrupt local officials had permitted substandard buildings. This news was covered up by governments at all levels. Subsequently harassed by policemen, Ai Weiwei and his followers regularly turned their cameras on their tormentors, constantly posting images and commentary. Following his eighty-one-day detention on fake tax evasion charges in 2011, Ai Weiwei created six iron boxes, scaled-down versions of the spaces in which he was detained. Each contained fibreglass figures of himself and his two ever-present soldier guards, furniture, and other details, vignettes from their unvarying daily routine. Entitled S.A.C.R.E.D, it was shown at the Chiesa di Sant’Antonin, Venice, in 2013 as a collateral exhibition to the then-current Venice Biennale.

Meanwhile, in China, his name is on the list of “topics” purged from public discourse. Everyone knows they are not meant to know about these topics. Since his exile following a brutal bashing, Ai Weiwei has focused on more general topics, such as the causalities of the refugee crisis, in a memorable installation at Cockatoo Island during the 2018 Sydney Biennale.

A second strategy is introversion: taking up the tropes of authoritarian control as the content of your art but turning them against themselves through techniques that resemble unfolding a glove inside out. In Wang Tuo’s video, The Interrogation (2017), photographs of film stills, and Photoshop collages present two parallel narratives. In one, triggered by Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona (1966), an actress portraying a mute actress and another playing a nurse trying to persuade her to speak gradually exchange roles. In the other, set in China, the artist interviews an official from the local Commission for Discipline Inspection branch. The official shares the psychological manipulation techniques he used during his job interview and explains how he applies the same techniques when interviewing people such as artists. As the two young men talk, changing positions on the furniture in a book-filled room, and camera angles switch and shift, a similar slow swap of identities occurs.

In The Second Interrogation (2022–3), two protagonists, one an artist, the other a censor of cultural work, meet at an art opening and fall into a discussion of the famous China Avant-Garde Exhibition held in Beijing in 1989 during the period of student protest, including at Tiananmen Square, when state repression became overt. Permission to show contemporary painting and installation art had been given, but “performance” was strictly forbidden because it allowed no time for prior approval. Despite this, seven artists staged performances that drew attention to some of the contradictions in play in Chinese society and the exhibition itself. Zhang Nian sat surrounded by eggs—as if hatching them. Wu Shanzhuan sold shrimp to ridicule the relationship between art and money. Xiao Lu used a pistol to fire shots at the installation about communication breakdown she had made with her partner Tang Song. The exhibition was too much for the authorities, who shut it down. Since then, surveillance, control, and careful self-censorship have come to saturate Chinese society and shadow art practice. Thirty years later, the artist protagonist in The Second Interrogation formed a group of dancers preparing a performance that reenacted the interventions of the seven artists. Yet he has become a covert agent rooting out ideological deviance in the contemporary art world. The censor, in contrast, has imbibed the values of artistic freedom and slowly takes charge of the performance, loosening and freeing it in an exhilarating way.

At the 2024 Asia Pacific Triennale, this work stood out, matched by a few others, one of which was Bombay Tilts Down 2022 by the Mumbai filmmaking collective CAMP. Across several screens, footage shot by CCTV cameras at the highest points in Mumbai—one an illegal high-rise, another a skyscraper favoured by white-collar criminals—pan downwards towards the ground-hugging slums. The structures of inequality and the architecture needed to maintain it are profiled as if in sections of an archaeological dig. Accompanying sound includes stirring music, silences, and revolutionary poetry and song.

These strategies invite us to nuance the standard meaning of “introversion.” They are compelling and immersive, mix direct address and indirect appeal, and are at once theatrical and absorbing—subversion from the inside out.

Why think about such strategies here and now? To most Australians, the idea that we might live in an authoritarian society is simply inconceivable. Not so for Indigenous Australians. The historical record from Settlement/Invasion to the rejection of the Voice to Parliament just last year is plain. Archie Moore is one artist who has created a work that registers that racist record yet transcends its deadly confinement by framing it within a larger narrative, indeed, the largest: the movement of the world through time. This resistant practice steps beyond the world pictures in contention, showing them to be lesser in scope than their claims to totality. This a worlding strategy.

Moore’s installation kith and kin for the Australian Pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale paired and contrasted black and white on several registers. At first look, it did so aesthetically, as every element in the room paired and contrasted the two colours, the two ends of an absent spectrum. The installation is grounded in a pool cut into the centre of the floor, its sides and base painted black. Filled with water, absorbing the colours around it, it reads as a black infinity that nonetheless captures whatever light falls on it, whatever movement of the air, whatever reflection of walls and ceiling the viewer sees. Country is like that, when thought about abstractly.

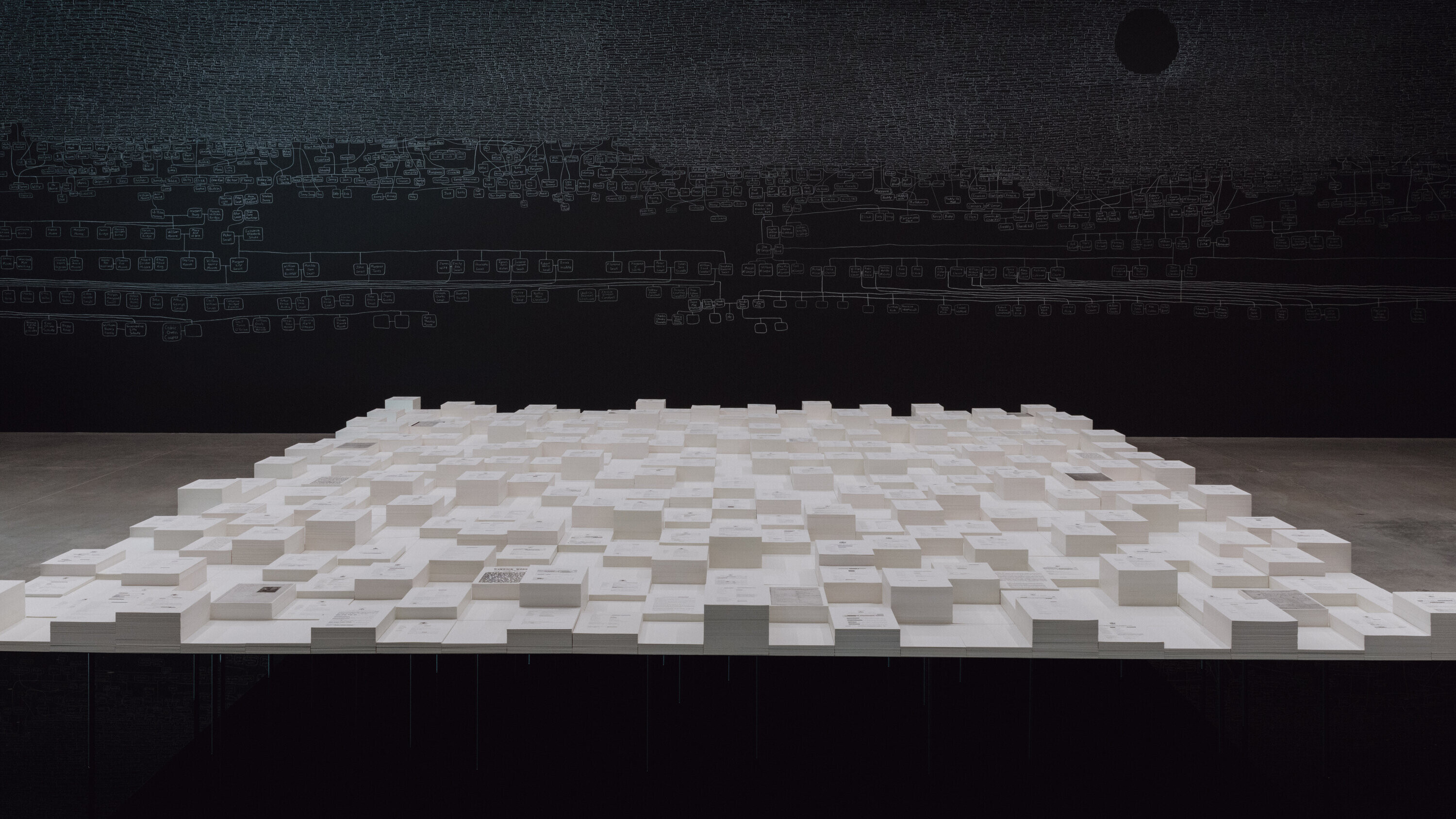

Above the pool, a suspended table contains uneven stacks of white paper, some blank, many printed. These are photocopies of official documents relating to the recording, studying, and supporting of incarceration, and the punishment of Indigenous Australians. Some members of Moore’s family are included. Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders constitute 3.8 per cent of the population of Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics tells us that, as of December 2024, of the 44,262 people in custody, 15,901 were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders; among the 82,823 serving custodial correction orders, 22,148; and of the eighty deaths in custody in 2023 and 2024, twenty-four were Indigenous. The table’s blankness evokes this slow suffocation by bureaucracy, enforced by incarceration. It is a white city of black death. But its finality is fragile, because it floats above the black infinity below.

And because it is slowly overwhelmed by what surrounds it. The four walls and the ceiling are painted with blackboard paint. With chalk, Moore drew a family tree of relationships branching outwards and back to himself, each member named within a small box, as in an ancestral chart. Its reach, however, is much wider, its resonance much deeper. In his curatorial statement of 18 April 2024, Moore says: “the phrase ‘kith and kin’ now simply means ‘friends and family’. however, an earlier old english definition that dates from the 1300s shows kith originally had the added meanings of ‘countrymen’ and also ‘one’s native land’, with kin meaning ‘family members’,” a usage that “feels more like a first nations understanding of attachment to place, people and time.” To Country, in a word.

In the chalk boxes, he names his Kamilaroi and Bigambul ancestors, to the extent that he can, given gaps in the records, their omission from or evasion of the colonial gaze. And he takes the further step of adding in the names of other Indigenous peoples from across Australia, names given by the colonisers and their names. As the tree reaches into the ceiling of the pavilion, making it a sky of memory, he includes the names of Indigenous peoples from elsewhere, then of colonisers, reaching back to the African ancestors of us all. Two black holes indicate the limits of records and the fading of memories. They are black holes into which visibility is drawn while, at the same time, fresh energy bursts to flow across the whole.

A table loaded with white, printed papers and handwritten names on the surrounding walls. There is a conceptualist lineage here, not least Joseph Kosuth’s Investigations series, which he began in the late 1960s. Kosuth provided texts and images inviting studious reading and sustained reflection along certain lines of thought—mostly thinking about thinking and the usefulness and limits of words in such thinking. The presumed framework was Western philosophy, especially one focused on language use and meaning.

Moore echoes the aesthetic of language-based Conceptual and Minimal Art installations, especially at the central table. Benjamin Buchloh critiqued conceptual artists for adopting what he called an “aesthetic of administration”, a presentational style that echoed the coercive control by bureaucracies. Moore contrasts this with the dark walls of kith and kin, which, inscribed by hand, invoke much older practices of marking the world’s surfaces—indeed, this marking reenacts the origins of language as the naming of other beings. It pictures us in the act of naming ourselves. Humanity, not as a universal, abstract concept, but as individual beings and families of the same kind, kin and kith.

The installation also records Moore’s four-month mark-making performance. Working backwards from the clustered ceiling down through layers that open up connections as they approach the present—typical of looking back towards the density of the past, here a cloud or tree canopy, not a historical line disappearing into invisibility—Moore reserved the last empty box for himself, into which he inscribed, not his name, but “Me.”

His statement reminds us that Country is like this, when thought about in once mythical and concrete ways. Such grounding is available to all despite being subject to constant erosion. This is anti-colonial world picturing at its most resonant. A worlding that is way more expansive and open than anything the autarchies have been able to conjure.

When kith and kin was awarded the Golden Lion at Venice, the jury praised it in these terms: “This installation stands out for its strong aesthetic, its lyricism and its invocation of a shared loss of an occluded past. With its inventory of thousands of names, Moore also offers a glimmer of the possibility of recovery.” An evident appreciation of a country with a culture capable of producing artists who expose its most profound contradictions, a nation willing to support its artists as they share these challenges on a world stage.

The same spirit seemed to animate Creative Australia when it proudly announced the appointment of Khaled Sabsabi and Michael Dagostino as the artist and curator team of the national pavilion at the 2026 Venice Biennale. They followed the same process that resulted in the appointment of Moore and curator Ellie Buttrose, choosing Sabsabi and Dagostino among sixty-one applications. In the 5 February 2025, press release, CEO Adrian Collette stated: “Khaled Sabsabi's work, in collaboration with curator Michael Dagostino, reflects the diversity and plurality of Australia's rich culture, and will spark meaningful conversations with audiences around the world.” Sabsabi would not go into detail about the work still in development but did say that he aimed for the pavilion to be “an inclusive place, it's a place that brings people together, and I like to use the word ‘nurturing.’” Given that he was making a public statement, his conscience led him to add: “as a human being, as a Lebanese, as an Arab, as a Muslim, as an Australian what's been happening in Gaza is inhumane and unacceptable.”

Perhaps it was this humane and entirely acceptable statement that alerted a troll searching social media for anything resembling criticism of Israel’s conduct in its war against its neighbours, most lamentably Gaza. Or maybe someone was stirred into action because they objected to Australia being represented by an artist from one of our immigrant communities, and journalists at The Australian were soon contacted. The Murdoch press, television, and social media have vocally supported Israel’s response to the inhumane and unacceptable attacks on Israeli citizens by Hamas operatives on October 7, 2023, even though that response has been widely condemned around the world as beyond excessive. Here, a spate of antisemitic attacks on synagogues and the homes of Jewish notables swiftly led to the strengthening of police powers and laws against hate speech and such violent acts. In Sydney, many turned out to be commissioned by local crime figures to divert or bargain with local police. This makes the attacks not less antisemitic, but doubly so.

The Liberal Party, in opposition, has not hesitated to pillory the federal government for being weak on Hamas in its defence of Israel and in acting against local antisemitism. On February 13, Senator Claire Chandler, newly appointed shadow arts minister, posed this question: “With such appalling antisemitism in our country, why is the Albanese Government allowing a person who highlights a terrorist leader in his artwork to represent Australia on the international stage at the Venice Biennale?”

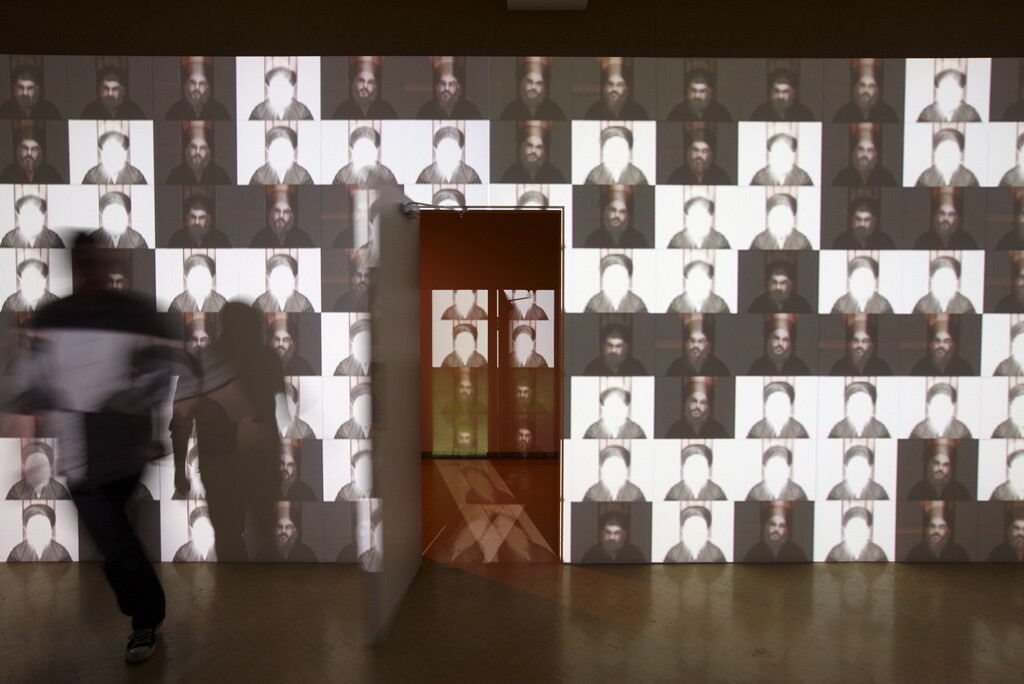

She was referring to Sabsabi’s multi-channel digital video installation YOU from 2007, which explores the range of attitudes held in Lebanon towards Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, who was assassinated by Israeli forces in September last year. “Highlights” is an accurate, if literal, description of some moments in the video where the leader’s image glows. Along with other works, it has been available on his website since its making, and has been exhibited since, not least at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. However, an unprejudiced viewing of its nine minutes reveals a wide variety of treatments, Warhol-style, of the image of Nasrallah. The same applies to the related photographs, which were heavily worked with oil sticks and acrylic. And of Sabsabi’s other early work that soon entered the debate: Thank You Very Much, 2006. The net effect is one of ambiguity, even equivocation, not a celebration of their ostensive subjects (see Carmen-Sibha Keiso and Giles Fielke on YOU and Rex Butler and Paris Lettau on Thank You Very Much)

Three hours after Chandler’s question was asked in parliament—during which time Tony Burke, Minister for the Arts and Leader of Government Business in the House, called Collette to discuss the issue, and a Zoom and phone meeting of the Creative Australia Board was convened—this statement was issued:

The Board of Creative Australia has made the unanimous decision not to proceed with the artistic team chosen for the Venice Biennale 2026.Creative Australia is an advocate for freedom of artistic expression and is not an adjudicator on the interpretation of art.

However, the Board believes a prolonged and divisive debate about the 2026 selection outcome poses an unacceptable risk to public support for Australia’s artistic community and could undermine our goal of bringing Australians together through art and creativity.

Creative Australia will be reviewing the selection process for the Venice Biennale 2026.

What has this precipitous, panicked, unprincipled reaction to do with my theme, the rising tide of autocracy and how visual artists might respond to it? If you need to ask… Chances are increasing that it may be seen as one of the early signs of a shift in that direction in our arts and culture. Especially when it was followed, a month or so later, by the decision by the leadership of Monash University to “defer indefinitely’” an exhibition, Stolon Press: Flat Earth, at its pathfinding art museum. The only evident reason is that it included works by Sabsabi—explicitly low-key, formal explorations. To justify their action, University officials used the same kind of weasel words that constitute the Creative Australia statement: “Through consultation with our communities, we have identified there is a need for the Museum to deepen its collaboration and engagement on this exhibition. Postponing the event will allow this important work to be undertaken.”

Under pressure, the Board of Creative Australia was willing to ditch its commitment to supporting artists and their institutional independence in favour of a newly discovered duty to preserve social cohesion. The aesthetics of administration—perversely, of arts administration—have become the institutional priority here, superseding those of the artists they are meant to serve. Whether under pressure or not, Monash University leadership is trifling with artistic freedom and questioning its curators’ exercise of academic responsibility.

There can be no doubt that swift but thoughtful action against any sign of antisemitism is imperative not only because the sentiment and actions that flow from it are harmful to Jewish people and thus destructive in themselves—as they are when anyone, any people, is singled out on the grounds of race or ethnicity—but also because, as the world witnessed in Germany, Italy, Poland and elsewhere in the 1930s, it is a clear sign of the fascism to come. Today, however, a dangerous, paradoxical irony follows from expanding definitions of antisemitism to include any negativity toward Zionism and the state of Israel, no matter what atrocities are committed in their name. This extends to any affirmation of the rights of Palestinians, especially their claims to any form of statehood. Governments, institutions, and donors have weaponised defence against antisemitism in this expanded sense to shut down the exercise of critical speech in arts organisations, universities and art institutions across the globe. The hounding of ruangrupa’s curation of Documenta 15, the Trump administration’s blackmail of Columbia and Harvard Universities, and the withholding of support for the Sydney Theatre Company and other arts organisations in this country. Creative Australia and possibly Monash University are recent additions to this sorry list. Such blanket, bad-faith defence of antisemitism for quite other purposes is turning into a signal of the autocracy to come.

As I write, Australia is in election mode, suspending major decisions and shelving minor ones until after May 3. Irrespective of such conventions, it is not too late for the Board of Creative Australia to revisit its decision, citing the strength of the response from the visual arts sector, which it is mandated to serve, and the need to restore that sector’s faith in the organisation. An apology to Khaled Sabsabi for the impact on him and his reputation—set out so forcefully by Josh Milani—would be nice; thank you. It would be a travesty of justice if the review —which keeps revising its remit, now excluding any review of the original decision and the rescission—ended up blaming the visual arts specialists within Creative Australia. Especially not Mikala Tai and Tahmina Maskinyar, who honourably resigned as soon as the CEO and Board made their dreadful decision. More broadly, the poisonous climate created by the antisemitic attacks has calmed to the extent that “prolonged and divisive debate about the selection” is unlikely to occur. If the Murdoch press and the Liberal Party hardliners continue to stir up social divisiveness, surely the Arts Minister and Creative Australia can summon the chops to resist it. Anti-woke shit-stirring is, after all, proving a losing strategy in the current campaign.

Since its founding in 1972, the Australia Council, now Creative Australia, has built up enormous credit among artists, arts organisations, and the public for the services it has provided and for the careful, professional, arm’s length, peer review way it has generally gone about its business. The decision of February 13 threw these principles and this hard-won reputation under the bad faith omnibus.

The word “integrity” appears in the first and last points of the Creative Australia Code of Conduct. For the institution's own good, and for the moral health of the arts in Australia, it is time for the Board to act to regain this essential quality.

Terry Smith is Emeritus Professor of Art History, University of Sydney, and Andrew W Mellon Emeritus Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory, University of Pittsburgh

Related

From Rhode Island School of Design‘s anti-commercial posturing to Gagosian’s prismatic salons, this fictional Anna Weyant chronicle exposes the brutal mechanics of ambition in contemporary art.

“There’s no path for the magazine to restore trust in its current ownership.” David Velasco and Kate Sutton reflect on the situation with Artforum and its Summer 2024 issue.