Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65)

I’m going to talk about Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65). But first, I’d like to detour from one exotic female body kneeling on the floor to another: Maria Martins’s Eighth Veil (1948). Hers is a life-size bronze of a limber, toned nude, seated on the ground, slumped as if she has collapsed from a kneeling position. Her supple legs bend outwards, high thighs and knees in front of her, the calves bending backwards. She steadies her posture by placing both arms straight with her palms touching the floor. She has turned her torso to her right, and her neck continues turning to position her head looking upwards toward something unseeable at her back. It’s a fascinating pose that withholds an unspoken narrative. It’s also testament to the unique perspective granted female form in the hands of a sculptress. Yet crowning the halting steely beauty of this body is a violently imploded head. Hairless and more resembling a bald knob than a head, it possesses a cranial shape with cheek bones and jaw line, but where facial features normally reside is a distressing cleft, sucking mouth, nose, and eyes into a frightening gash, and expelling a pulped aggregation of their components.

Exclusive to the Magazine

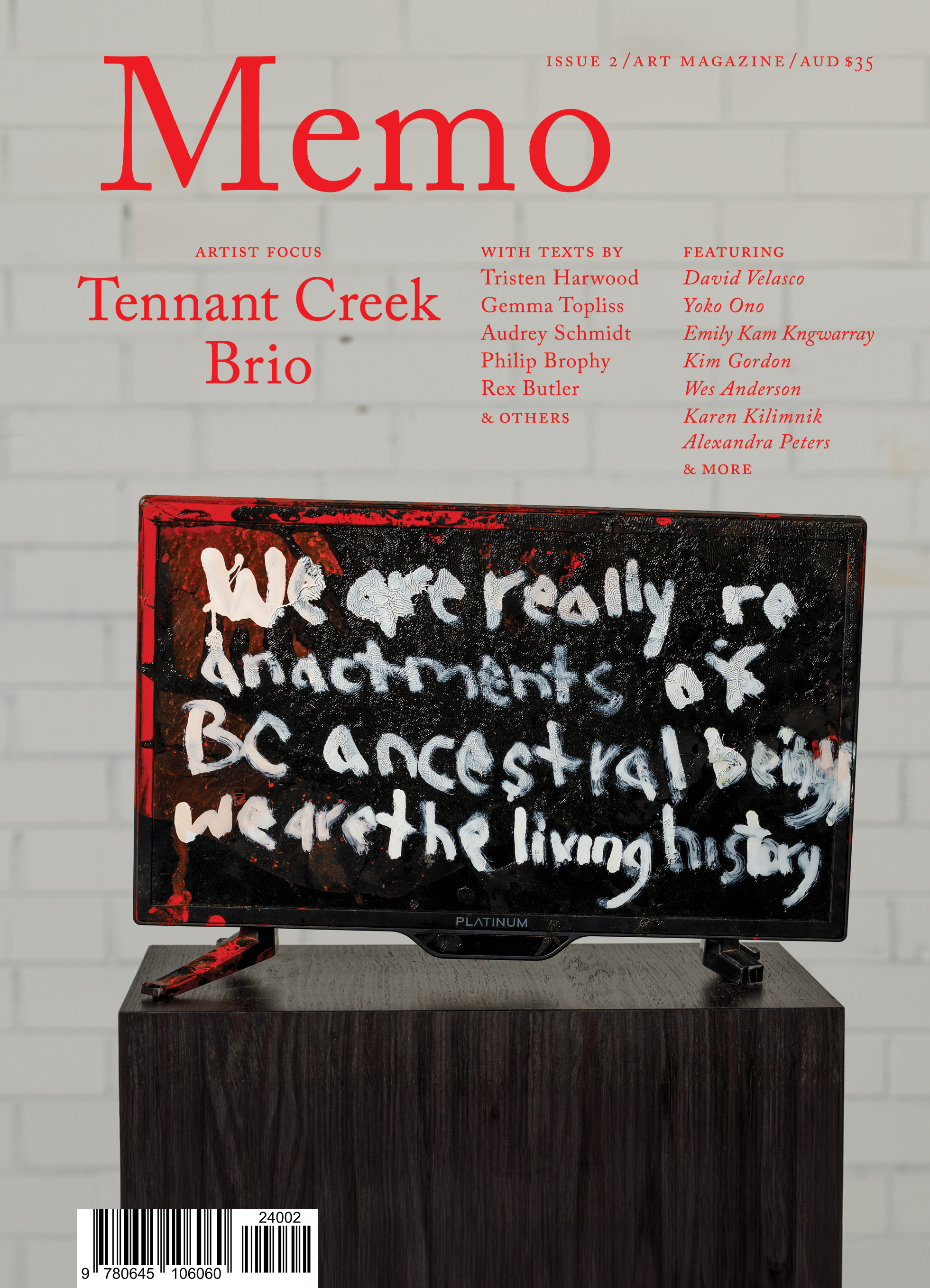

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65) by Philip Brophy is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Dean Kissick’s Downward Spiral chronicled the art world’s contradictions with the breathless urgency of an end-times prophet. Now, with the column closed and the critic in semi-exile, the question lingers: was he a voice of his generation, or just another scenester burning out on his own myth?

“It is no longer my face (identification), but the face that has somehow been given to me (circumstantial possession) as stage property.” — Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Omnicide: Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium

Kim Gordon grinds handrails with a Jazzmaster, vacuums in MNZ heels, and sings of capitalism’s end while modelling for its tastemakers. Object of Projection channels the aesthetics of resistance, but is it rebellion or just another symptom of “conservative cool”?