To Emily Up Above

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art has been claimed, framed, and re-framed—by critics, curators, and institutions alike. But what remains of the singular, personal encounter with her work?

Of course, we’ve all had the art experiences you know you’re going to have, the ones your whole culture tells you everyone has. I’ve stood under the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and seen the swirl of God’s drapery — and, indeed, God’s bum — while he’s creating the sun, moon, and planets, and wondered how any human was able to paint like that. I’ve turned round from Rembrandt’s The Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum and imagined — wrongly, it turns out — that I was one of the men deputed to guard the city, looking out into the inky-black night, which stands in for the mystery of the cosmos and our own small place within it. I’ve put my nose up against a Frida Kahlo self-portrait in a touring show in Canberra, astonished at just how slick and seamless the paint was, and somehow grateful our culture has seen fit to celebrate someone as unconventional as the bed-ridden and monobrowed Kahlo, making her the possessor of one of the faces of the twentieth century. But these aren’t the experiences that make you, that enable you to discover who you are, that seem to be for you and you alone, and for you to think about as though you were the first to do so. The ones that, if you added them together, would form some kind of interlocking jigsaw whose solution could only be you. (Of course, you also know, even as you are experiencing them, that to think about them this way is a terrible self-aggrandisement, and that maybe even the work is telling us this.)

Exclusive to the Magazine

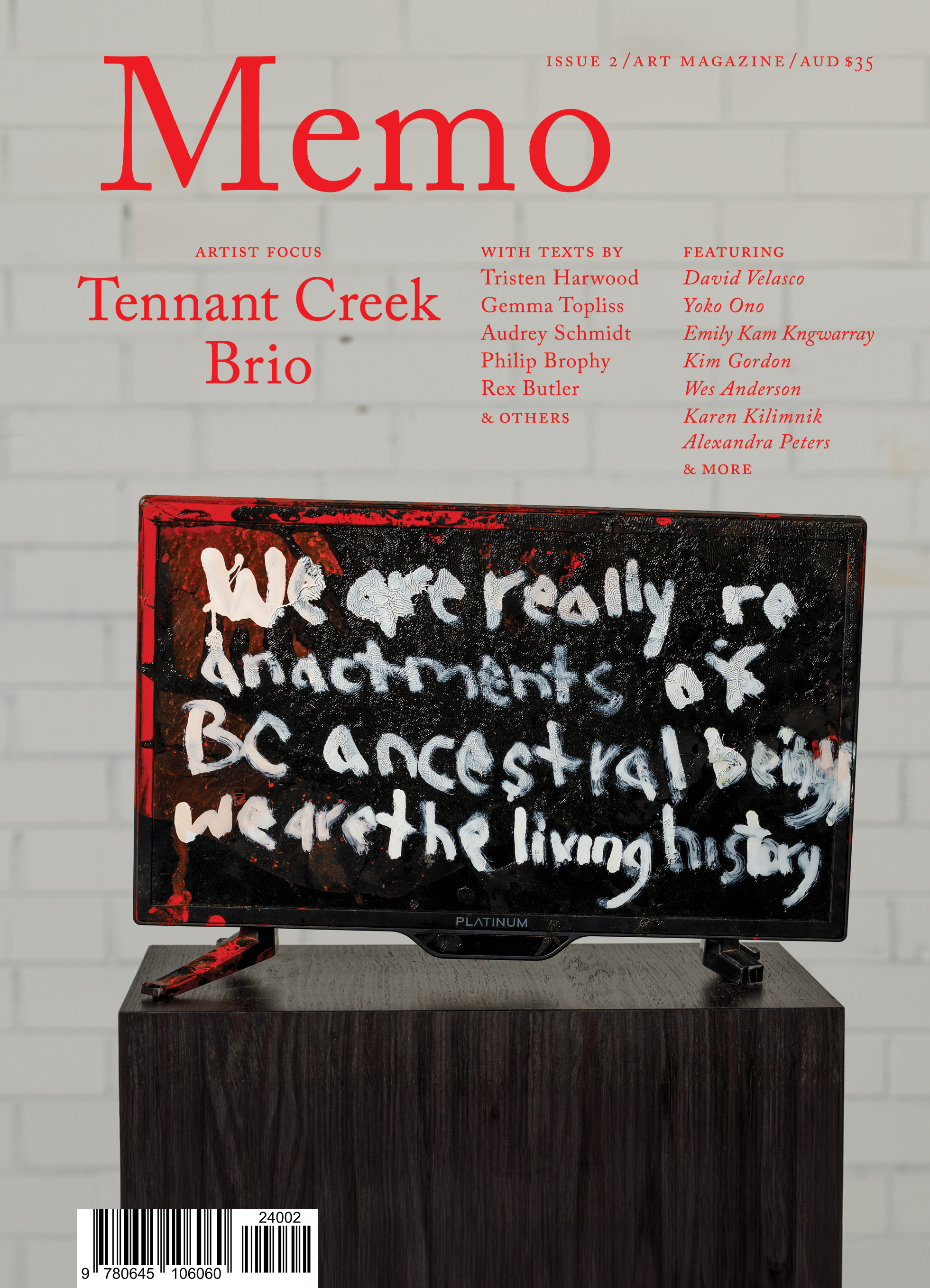

To Emily Up Above by Rex Butler is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993) is a film without images—just a luminous ultramarine field and an evocative soundtrack. Made as he was dying of AIDS-related illness, Blue resists spectacle, embracing abstraction, memory, and loss. Thirty years on, it continues to evolve, expanding across artists, mediums, and generations.