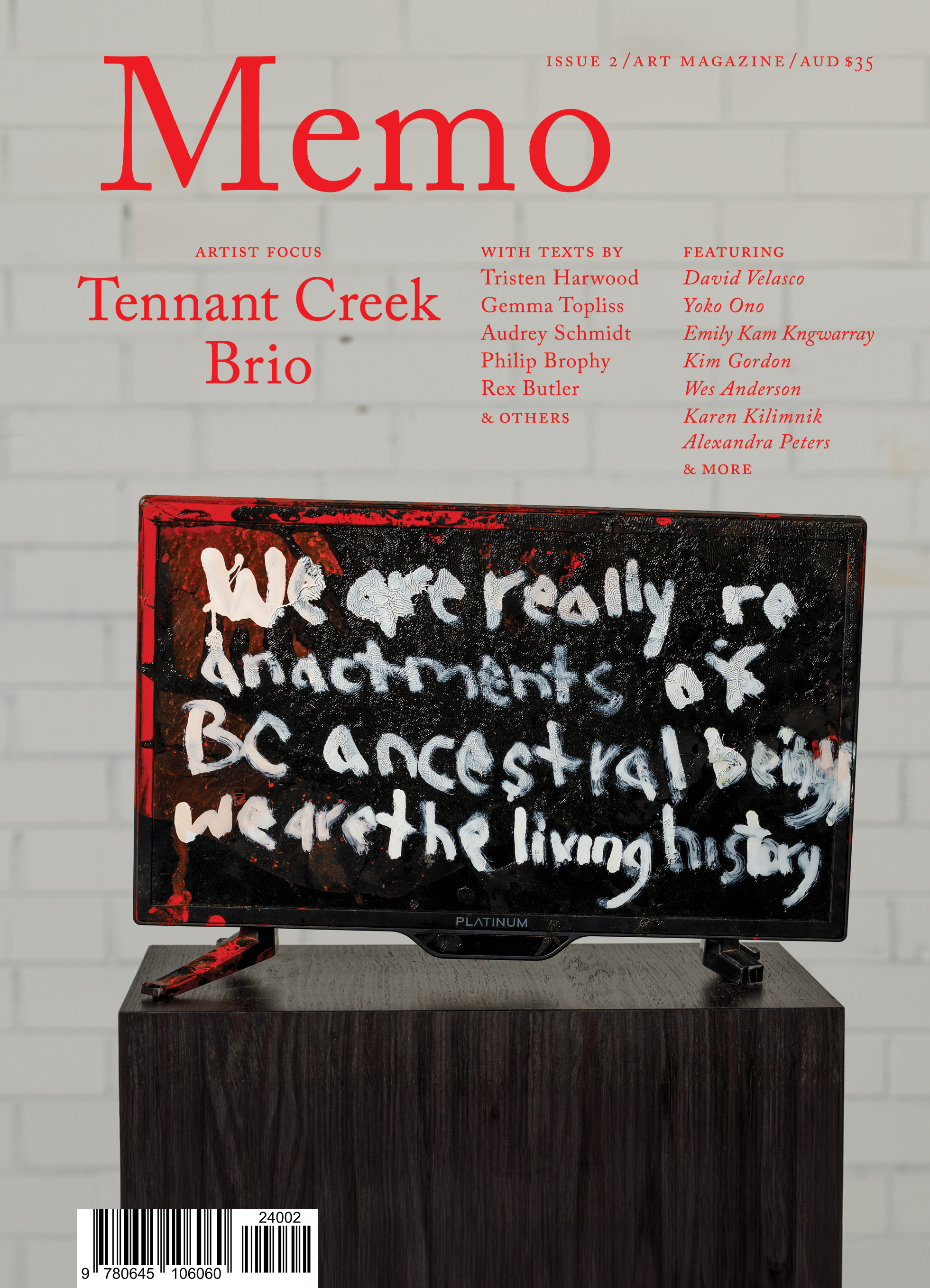

Shock of the New

The Tennant Creek Brio transform mining maps, dead TVs, and frontier wreckage into new cultural claims—rejecting imposed “otherness” and forcing the settler gaze into confrontation. If their art is a shock, who’s really being unsettled?

“Hell is others.” It’s probably not the best way to introduce an artist collective founded on the idea that strength comes from working together, that the harmonious whole is greater than the individual parts. But “hell” and its various connotations does relate to the work of the Tennant Creek Brio and to the Italian word “brio” itself, which signifies “fire” as both a destructive and creative force. “Hell” might relate to contemporary life at Tennant Creek, or at least how it’s generally depicted in mainstream reports as a broken-down town best passed through on the way to and from Alice Springs or the so-called Devil’s Marbles nearby.

Exclusive to the Magazine

Shock of the New by Maurice O’Riordan is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

By recasting Black-Eyed Sue and Sweet Poll in shackles, Sayer’s 1792 engraving subverts the sailor’s farewell to reveal convict and naval cruelty as mirror images.